True Grit

By Brian Eggert |

Swaggering with the confidence of a bear, John Wayne was a presence in the movies. A dear and highly revered celebrity among moviegoers, The Duke earned his legend through absolutist characterizations, only occasionally offset by rare, complex performances like those in John Ford’s The Searchers and The Long Voyage Home. His presence onscreen was enough to make a movie better, if only because he carried such a personality on and off camera. The actor rarely, if ever, played a character that wasn’t a few shades similar to himself, but it was that inarguable honesty in his performances that helped solidify his legend. The problem with legends, however, is that they can become overstated and embraced merely because they’re legends. Take the 1969 version of True Grit, an adaptation of Charles Portis’ novel, published the year before. The film earned Wayne his first and only Academy Award for Best Actor. That award might have been the equivalent of a “lifetime achievement award” for voters, who no doubt felt, perhaps correctly, that such a legend as Wayne should have an Oscar by now. But the film itself, directed by Henry Hathaway and produced by likewise living legend Hal B. Wallis, was little more than a “John Wayne movie” through and through. It works because of Wayne and Wayne alone, whereas the other actors, the direction, and the gratingly ‘60s production values fail to live up to Wayne’s enormity. And yet, it goes down in film history as a beloved offering from The Duke.

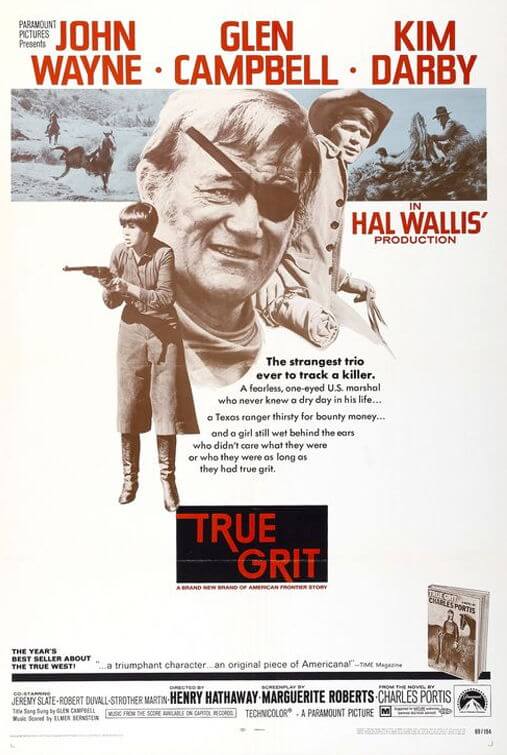

Set in the 1880s, the idyllic Western screen story begins when no-nonsense 14-year-old Mattie Ross (Kim Darby) declares her intent to track down her father’s murderer. She seeks out the meanest U.S. Marshal she can find and hires him for the job. Enter Rooster Cogburn (Wayne), the boozy, cantankerous, eye-patch-wearing grouch whose trigger finger is almost as loose as his manners. After much bargaining, they brave dangerous territory together with a young Texas Ranger, La Boeuf (Glen Campbell), who’s after the same killer, the dastardly Tom Chaney (Jeff Corey). But Chaney has aligned himself with “Lucky” Ned Pepper (Robert Duvall), leaving our heroes outnumbered. Not that it matters, as John Wayne is never outnumbered.

Recognizing the bold role that is Rooster Cogburn, Wayne placed a bid on the film rights to Portis’ novel for $300,000 but found himself quickly outbid by Wallis, who in turn hired Wayne on as the leading man. With Wayne as the lead, the filmmakers could hardly remain true to Portis’ novel, which is told from Mattie’s point of view and considers Cogburn only a supporting character. After all, this is John Wayne, dammit. And so, Mattie remains the central protagonist for the opening scenes, which, for the most part, involve discussions of Cogburn’s notorious legend before she hires him. Once Cogburn makes his first appearance onscreen, he’s been talked about enough that his entrance feels something like Harry Lime finally emerging from the shadows in The Third Man. It’s what Orson Welles called a “star vehicle,” in which “What counts is how much the other characters talk about you. Such a star vehicle really is a vehicle. All you have to do is ride.”

Indeed, Wayne rides the Cogburn role without giving any breakthrough dimension to the character or his persona as an actor. His aversion to subtlety intact, Wayne gives one of his greatest larger-than-life performances as Rooster Cogburn, the size of which, if attempted by another actor, would seem cartoonish. Or, perhaps Wayne’s portrayal is slightly cartoonish, but the actor is permitted such extravagances because his legend does not waver. Those over-the-top expressions soar above everything and everyone else onscreen, leaving the other actors rightfully dwarfed by Cogburn’s assertive drinking, forced slurred speeches, and heroic shootouts—all complete with those Wayne-isms that, to audiences in 1969, were so familiar and fondly remembered from Wayne’s heyday in decades prior.

As for the other actors, True Grit offers early screen appearances by Duvall and even Dennis Hopper, both playing generic Western villains, both yet to find their own screen signatures. Hopper is barely recognizable, and Duvall doesn’t even try challenging Wayne’s domination of the screen. It shows that Darby was well into her twenties when production began. She’s awkwardly playing a teenager whose strong-headedness, despite her youth and innocence, is supposed to take both the audience and Cogburn by surprise. And yet, due to her visible maturity, she never captures how she is the one with true grit that Portis intended. In addition to being much too old for the role, her wooden performance further drives the viewer toward Wayne for a hearty dose of colorful acting. Likewise, Campbell’s squeaky-clean supporting role has little personality or depth, and his appearance onscreen equates to Ricky Nelson’s in Rio Bravo—a young music star whose musical contributions to the film helped sell the soundtrack.

Elmer Bernstein, who earned an Oscar nomination nine years earlier for his memorable score of The Magnificent Seven, plays it just as loud and overwrought as Wayne, except without the actor’s undeniable charm. While hints of The Magnificent Seven’s theme are embedded into the Western score here, the music is also pointedly of Hollywood circa 1960s, rarely committing itself to the period setting. Moments of dramatic tension are completely lost due to the overreaching score, whereas horseback traveling scenes attempt a failed grandiosity to match the otherwise impressive backdrops (the film was shot on location in the Rockies, around Ouray County, Colorado). Rarely has a score felt so out of sync with its film. Or, perhaps Bernstein merely hoped to compete with Wayne’s thunderous performance by drowning out all senses other than aural.

But the music is just a symptom of True Grit’s lack of artistic drive. Hathaway had long been a studio director, taking whatever projects the studio gave him and delivering a good product on budget and with reliable technical skills. His career began with a Western, Heritage of the Desert of 1932, and then developed into dynamic film noir productions such as Kiss of Death and The House on 92nd Street during the next decade. But, aside from his foray into high contrast noir, Hathaway primarily delivered serviceable pictures in the typical, flat style demanded by studios. By 1969, he had collaborated with Wayne seven times, all on Westerns. Here, Hathaway handles the movie like a tired veteran director, going through the motions, completely satisfied with the same old tricks. Aside from his gorgeous location shooting, his lack of directorial flourishes leaves the screen for Wayne to fill.

The Duke was well aware of his popularity and his importance to True Grit, and he took every advantage. In Gary Willis’ biography John Wayne’s America, the author notes that Wayne, a famous drinker, insisted that the whiskey drank by Rooster Cogburn be actual Kentucky bourbon, not prop whiskey. During one of the actor’s uglier, drunken moments on set, he announced to the cast and crew, “This is my show, you’re just along for the ride!” Although, his willingness to embody the ‘old fat drunkard’ stereotype at his age—he was in his sixties while filming—was brave, given that his youthful origins in the Golden Age had long since passed. Other iconic stars his age struggled to grow with the new post-studio-system Hollywood. Fearing the changing industry and their long-since-gone youth appeal, such performers either retreated into retirement (like Cary Grant) or simply faded out of pictures (like Errol Flynn) and thus the limelight altogether. Wayne’s status persisted until he died in 1979, but his performances grew increasingly complacent.

When True Grit was released, it hardly mattered to audiences how much the adaptation diverted from the source material to meet the requirements of a “John Wayne movie,” if only because it was a John Wayne movie. Every aspect of the production seems to rely on that fact. The filmmakers lean on Wayne, who gives die-hard fans access to a rich performance that, for many, forgives all else that remains so clumsy about the picture. When compared to Wayne’s work with Ford, well, there’s no comparison at all. Ford’s Westerns were about the setting and the story, whereas Hathaway has no intent on making his movie about anything else than Wayne’s memorable role. If only he had given the performance in a better movie.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review