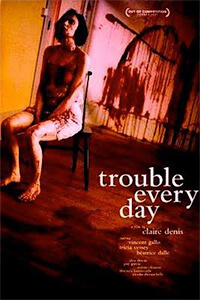

Trouble Every Day

By Brian Eggert |

Sexual desires turn into feverish cannibalism in Claire Denis’ Trouble Every Day, her maligned 2001 release that has since been reassessed and appreciated through the lens of the “New French Extremity.” The term, conceived by James Quandt in an influential 2004 article in ArtForum, describes a tendency in French cinema since the late 1990s to embrace shocking sexuality and violence, and often their interrelation. Films by otherwise unconnected “New French Extremity” filmmakers—such as François Ozon, the author of sensual thrillers; Gaspar Noé, provocateur extraordinaire; and Philippe Grandrieux, miner of psychologically dark places—transgress standards and provoke through an artistic evacuation of taboos: graphic rape, serial killers, bloody viscera, sadomasochism, bodily fluids of all manner, engorged sexual organs, unflinching sexuality, and cannibalism. Such material is not employed in a base shock-for-shock’s-sake manner, according to Quandt, but in an active artistic movement to subvert the expectations of moviegoers and critics. For Denis, whose Trouble Every Day is arguably her only venture into the “New French Extremity,” the film might represent an intentional purge to clear out the sexual anxiety and violence against the body that linger under the surface of her work.

The trouble begins with a characteristic French beauty, Coré (Béatrice Dalle), using her pouty lips and pronounced diastema to lure a trucker for a roadside shag. We see the results of her trap when her husband Léo (Alex Descas), a physician on a motorcycle, spots familiar signs of her predatory behavior. He finds Coré slumped in a field in a sort of post-coital stupor, blood caked around her mouth and sprayed on her body, and the trucker’s corpse nearby, the face mashed and gnashed. He takes his wife home, cleans her off with a damp sponge, and locks her in the bedroom while he sees patients during the day. Similarly afflicted by a sadomasochistic bloodlust is Shane (Vincent Gallo), another doctor whose new bride June (Tricia Vessey) is the subject of his disturbing, desanguinated dreams. They’re on their honeymoon to Paris, where the two, who have apparently never made love, stay together in a hotel, but he resists consummating the marriage in fear of tearing her to shreds—when things get hot, he rushes to the bathroom to finish himself, his new wife banging on the door. At the same time, Shane wants to locate Léo, his former Big Pharma colleague who has since been exorcized from the medical community, to find a cure for his lab-created condition. Unfortunately, Shane doesn’t know about Coré, and that if Léo had a cure, he would have used it already.

The machinations of the plot are less compelling that Denis’ use of form to investigate the body, as opposed to her rather underdeveloped characters and interpersonal situations. There is a tendency in Denis’ work to make the body a site of examination, such as the effects of colonialism on the body in Chocolat (1988), Beau travail (1999), or White Material (2009). Denis often sensualizes the body through action, notably violence and sexuality, though sometimes she explores the physical space of the body as a corporeal reflection of her characters, as observed in Let the Sunshine In (2018). This quality of her work raises Trouble Every Day from a chunk of gory horror moviemaking into, first and foremost, a nasty work of art. Her opaque characters inhabit equally amorphous situations, and their bodies become subjects within the frame, as their movements and actions have meaning beyond the context of those actions. She places aesthetic value on physical behavior, small gestures, sexual pleasures, and violent breaches—as though each were a stanza in another of Denis’ poetic, cinematic verse.

Max Nelson wrote in Film Comment that Denis’ films “have always been shot through with a current of menace just waiting to be made explicit.” Trouble Every Day allows Denis to bring to the surface elements of her characters that are otherwise implied through their sociopolitical, philosophical, or emotional states, using, as great horror films often do, violence and bloodshed as a metaphor. The violence here erupts into great surges that the viewer comes to dread. In one subplot, a small-time thief (Nicolas Duvauchelle) breaks into Léo and Coré’s home. After he finds Coré boarded up in her room for the world’s protection, she comes on to him, and the thief quickly finds himself bitten to death during intercourse. Another strain ends in a similar display of eroticism and mastication when Shane stalks a hotel maid (Florence Loiret Caille) into the locker room where he rapes her and bites her vagina. Before these deaths, Denis spends a considerable amount of time onscreen with both victims, even if we learn almost nothing about their lives. It’s as though she wants us to become accustomed to their bodies if only so we can watch their destruction.

Max Nelson wrote in Film Comment that Denis’ films “have always been shot through with a current of menace just waiting to be made explicit.” Trouble Every Day allows Denis to bring to the surface elements of her characters that are otherwise implied through their sociopolitical, philosophical, or emotional states, using, as great horror films often do, violence and bloodshed as a metaphor. The violence here erupts into great surges that the viewer comes to dread. In one subplot, a small-time thief (Nicolas Duvauchelle) breaks into Léo and Coré’s home. After he finds Coré boarded up in her room for the world’s protection, she comes on to him, and the thief quickly finds himself bitten to death during intercourse. Another strain ends in a similar display of eroticism and mastication when Shane stalks a hotel maid (Florence Loiret Caille) into the locker room where he rapes her and bites her vagina. Before these deaths, Denis spends a considerable amount of time onscreen with both victims, even if we learn almost nothing about their lives. It’s as though she wants us to become accustomed to their bodies if only so we can watch their destruction.

To watch scenes of Coré and Shane devour their victims in bouts of feral sexual hunger is to see humanity inhabiting two extremes at once. The way Dalle’s teeth chatter as she bites her victim’s lip is contrasted by the way she nuzzles his dying body. It’s a primal and incongruous reaction that, in another way, recalls how a dog tears apart a stuffed toy and then curls up with it for a nap. This blending of traditionally mismatched emotions lies at the core of the New French Extremity. As Adam Nayman and Andrew Tracy have pointed out, such films may vary in theme and intent, but what they have in common is “a loose agglomeration of cultural attitudes, as opposed to thought or theory.” They’re not similar in the sense of the French New Wave or Italian Neorealism, in that there’s no consistent philosophy or school of filmmakers driving them, just an anti-philosophy. Of course, even extreme denials represent a worldview. But Denis seemed to explore the aesthetic qualities of this movement, subgenre, or promotional brand in Trouble Every Day only briefly. Afterward, she returned to tone poems and thoughtful ruminations.

Regrettably, the quality of the film is single-handedly upset by the presence of Gallo, who looks like a recovering vampire on the verge of a bender. Gallo is an uneasy screen presence with his soft-voice, ratty hair, and sharp features, and Denis is quick to point out that he looks like a gargoyle atop of Notre Damme, or perhaps Lon Chaney in The Phantom of the Opera (1925). The already contrived expositional scenes in a French lab are made worse by Gallo’s flat line readings. And however uncertain the viewer may be about what’s going on and why, there’s an unnerving fascination at work when her camera pans over dozens of plants growing in testing jars, or the scene when a scientist extracts black veiny tissue from a delicately sliced portion of human brain. Never mind what any of this means in terms of the context of the story. The specifics of what caused Shane and Coré’s malady is less significant than how Denis implants the notion that our bodies, in all their desires and vulnerabilities, ultimately compel, drive, and destroy us.

Trouble Every Day was released shortly after Denis’ lauded masterwork, Beau travail, and many critics, comparing it to her earlier and less genre-saturated work, derided the result. Philip French in The Guardian called it “a risible disaster,” and Stephen Holden in The New York Times called Denis’ approach nothing more than “preliminary notes for a science-fiction horror film.” Clearly, some critics were unable to get beyond the surface subject matter and sheer redness of the material. But Trouble Every Day deserves reconsideration as a film that employs horror as a device for commentary first, revulsion second. Similar to the body horror of David Cronenberg, Videodrome (1983) and The Fly (1986) above all, Denis shows the mind-body dichotomy at its most fractured and upset. She treats violence with the same lyrical intention as a descriptive device in a poem, and her film is less a work of horror than poetry.

Sources:

Beugnet, Martine. Claire Denis (French Film Directors). Manchester University Press, 2004.

Mayne, Judith. Claire Denis. University of Illinois Press, 2005.

Vecchio, Marjorie, editor. The Films of Claire Denis: Intimacy on the Border. I.B. Tauris, 2014.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review