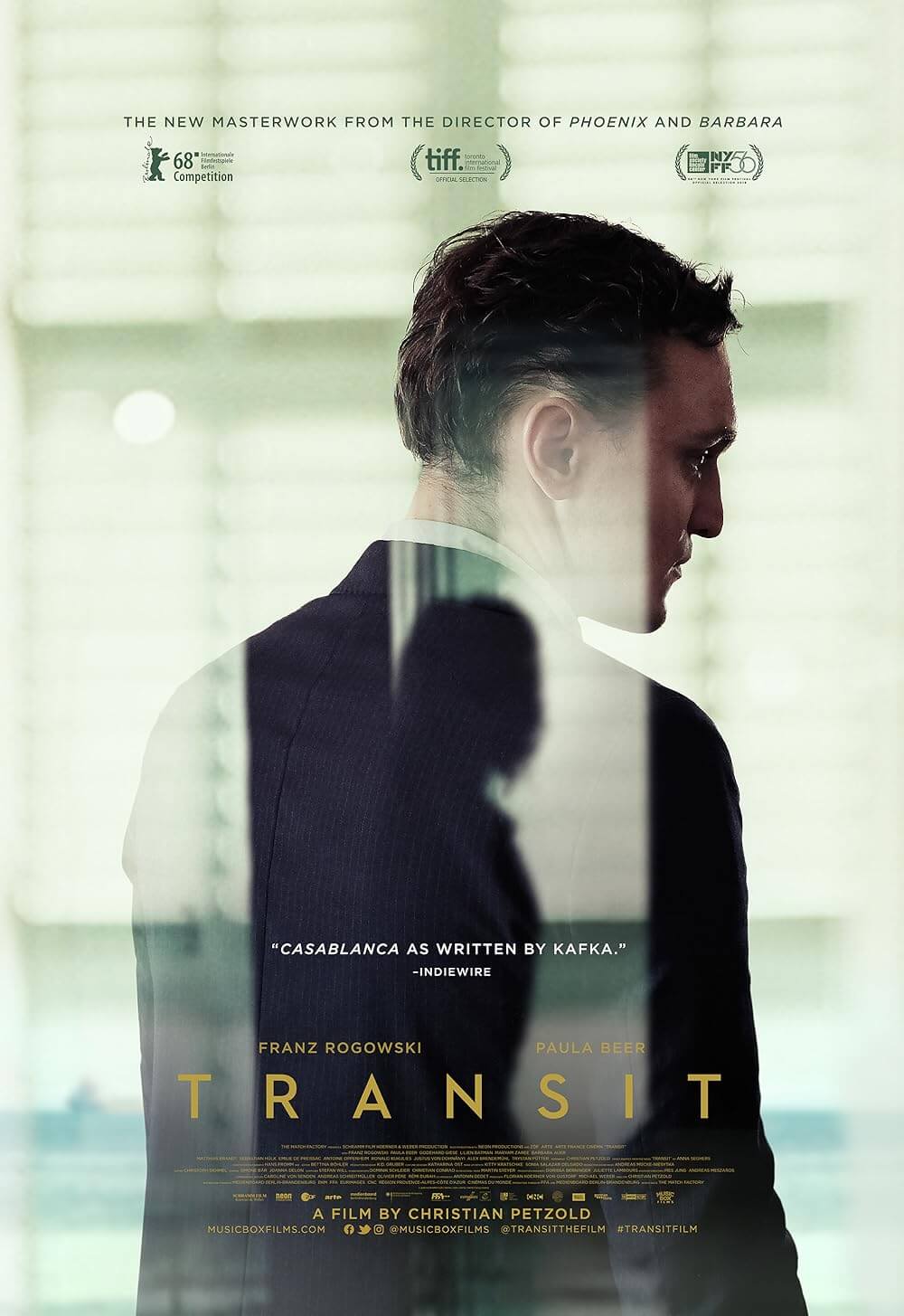

Transit

By Brian Eggert |

In Christian Petzold’s Transit, Barbara Auer has a small role as a woman looking after two dogs whose owners have since escaped to North America, evading the tide of fascism flooding Europe. She remains in Marseille, looking after the animals, hoping to get out before the regimen invades. She waits in long lines, hoping to receive the appropriate paperwork to leave. She’s hungry and desperate. And her fate seems inevitable. Before long, she wants to feel human again, just one last time. She puts on her most beautiful dress and invites a man, a veritable stranger with whom she’s shared a few momentary words and glances in the same lines for transportation documents, to share a meal. After they eat and toast to good health, she throws herself from a balcony not far from the Museum of European and Mediterranean Civilisations, built in 2013. What might seem like a scenario ripe for specific historical contextualization is even more potent as a story that transcends history. A fascinatingly conceptual film, Transit is another masterpiece from the German director and an urgently relevant symbolization of the contemporary refugee crisis. It’s all the more telling that the material derives from a story set during World War II.

Petzold based his screenplay for Transit on Anna Seghers’ 1942 novel of the same name, but he relocates the subject matter for a stark modern-day correlation. Seghers used her own experiences in Nazi-occupied France to tell the story of a concentration camp escapee who must maneuver between fascist threats to secure passage to North America. Petzold resituates the story to contemporary Marseille, although his treatment of time and place have an elusive quality that cannot be called simple modernization. There’s no mention of Nazis or the “Jewish question,” for instance. The presence of widescreen televisions, soldiers carrying the latest weaponry, and newer vehicles, briefly glimpsed in the background of some scenes, suggest that Transit takes place today. But also note the lack of smart devices such as phones or computers; instead, you will see typewriters and notebooks. In carefully described ways, this is an analog, paperwork-dominated, and bureaucratic world in which digital communication and instant gratification have no place. Similarly, characters do not travel with ease; they’re forced to ride trains or board passenger boats.

Transit is a film about being caught between states, and its ambiguous setting enhances this theme. The characters hope to escape German fascism to either Mexico or the United States, but they’re trapped in Europe. They’re cornered by an ocean that prevents their escape and a political force that limits their freedom. Time and reality, at least the viewer’s understanding of them, also betray the characters. They inhabit a world neither wholly of the past nor entirely of today; the film never refers to specific political situations, neo-Nazism, or the rise of extreme right-wing ideologies. Petzold places his film’s setting and characters outside of time. The streets of old Paris and Marseille where the film takes place look very much the same then and now. The characters sometimes look, dress, and behave like people from the 1940s. These choices signal the allegorical intention of the film, recalling something akin to Franz Kafka—whose novella In the Penal Colony, for instance, introduced almost futuristic technology in a French colonial setting. Although removed from a Kafkaesque journey into the fantastic and surreal, Transit does embrace themes of transitioning identities and paranoia.

Transit is a film about being caught between states, and its ambiguous setting enhances this theme. The characters hope to escape German fascism to either Mexico or the United States, but they’re trapped in Europe. They’re cornered by an ocean that prevents their escape and a political force that limits their freedom. Time and reality, at least the viewer’s understanding of them, also betray the characters. They inhabit a world neither wholly of the past nor entirely of today; the film never refers to specific political situations, neo-Nazism, or the rise of extreme right-wing ideologies. Petzold places his film’s setting and characters outside of time. The streets of old Paris and Marseille where the film takes place look very much the same then and now. The characters sometimes look, dress, and behave like people from the 1940s. These choices signal the allegorical intention of the film, recalling something akin to Franz Kafka—whose novella In the Penal Colony, for instance, introduced almost futuristic technology in a French colonial setting. Although removed from a Kafkaesque journey into the fantastic and surreal, Transit does embrace themes of transitioning identities and paranoia.

The story follows Georg (Franz Rogowski), a young man on the run in a fascist-ruled Paris, where the presence of sirens and police in riot gear indicate an uncertain threat. Desperate for money, Georg accepts a task to deliver some letters to a wanted communist writer, Weidel. But when he brings the letters, he finds Weidel has killed himself. Taking Weidel’s things, including an unfinished manuscript, Georg makes his way to Marseille, where he plans to assume Weidel’s identity to secure himself passage to North America. Once there, however, he learns that Weidel’s wife, Marie (Paula Beer), combs the cafés, streets, and official buildings in search of her husband. More than once, Marie stops Georg in the street, convinced that she had seen her husband from behind. At the same time, Georg has contacts in Marseille under his own identity, among them the family of a fellow traveler who died after their escape from Paris, the deaf widow Melissa (Maryam Zaree) and child Driss (Lilien Batman). As both a potential replacement lover for Marie or a surrogate father for Driss, Georg teeters between roles he could occupy, neither of which are his own.

Much of the film involves Georg trying to secure a seat on a ship or arrange safe travel for others. Passing himself off as Weidel affords him an unexpected sum of money and a degree of trust with the American and Mexican consulates. He’s able to secure transit papers and a spot on a boat for himself. But Georg becomes increasingly invested in helping the North African mother and child, to the extent that leaving them behind is preventing his escape, yet they have their own plan: a dangerous journey over the Pyrenees mountain range. This is a condition of many others in the film, such as Richard (Godehard Giese), who carries on in an affair with Marie, and refuses to leave Marseille because he loves her. The city, virtually abandoned and just waiting for the fascist party to arrive, becomes a place haunted by what was and what’s coming, and those leftover remain in flux. Georg goes back and forth, frantically trying to convince Richard to leave or to get papers for Marie. And during that time, his identity remains uncertain.

Identity is a shifting prospect in Transit, where the right name on forged documents might mean a better life. This is a recurrent theme in Petzold’s work after his last release, Phoenix (2014), about a concentration camp survivor who has facial reconstructive surgery only to go unrecognized by her husband, a detail she uses to adopt another identity and spy on him. That film starred Petzold’s longtime collaborator Nina Hoss, whose character resembles Beer in her role as Marie in Transit, as both have dark wavy hair and are distinguished by their stark red dresses. Likewise, Marie seems split between Georg, her late husband (whom she refuses to believe is dead), or Georg as Weidel. Because of this uncertainty, Georg is never quite sure who he is with her, himself or the identity he’s stolen. These shifting states of being accentuate how the coherence of self becomes disrupted when a government deems a group of people unwelcome, thus displacing both their literal and figurative states. Now imagine this condition on a mass scale, affecting the millions of refugees throughout the world, and Transit begins to ache.

The quality of the film as a moral story, featuring a lesson to be learned about the past and today, is furthered by the presence of voiceover narration, told from a second-hand witness to the events as described to him by Georg. The mostly unseen barman (Matthias Brandt) watches some of the action from a distance—he’s rarely in the frame. At other times, he admits in his voiceover that he heard about the film’s events from Georg. This conceit, which sometimes uses voiceover to describe minute actions that appear onscreen anyway, has a literary quality that enhances the film’s function as allegory. So too does the simple aesthetic approach, including the rather straightforward cinematography by Hans Fromm or the understated score by Stefan Will. Whereas Petzold could have done something more romantic and dangerous as Phoenix here to draw out the apt comparisons between Transit and Casablanca (1942), he reaches for the tragic, if not mysterious, in his attempt to portray the desperation and sacrifices that occur in dire situations under occupational rule. It’s a recessive kind of film, one onto which the viewer must project.

What Petzold underscores in Transit are the parallels between two periods in time—between eras of fascism, nationalism, and bigotry that existed both during and before World War II, and strains that emerge today, building to an inevitable head. It’s worth noting that many other reviewers have chosen to write about the film as though Petzold was portraying two separate worlds at once, as opposed to a distinct world of his own design, with remnants of the past interspersed amid signs of today. Viewing Transit as a temporally fractured and reassembled piece of filmmaking would emphasize its commentary more than its dramatic effort, turning it into something altogether Brechtian. In this case, the self-aware film would cease to have an emotional impact because it would be more concerned with itself as an amalgamation or distortion of known realities. But this is not a cold viewing experience that places the viewer at an intellectual distance. Similar to his melodramatic and high-concept plot in Phoenix, Petzold also uses the scenario here to create a link between contemporary filmmaking and a Sirkian brand of melodrama attributable to the postwar era of classical Hollywood.

The conceptual nature of the story, combined with our emotional investment in the fates of Georg and Marie, render Transit something beyond a film set during World War II that simply incorporates modern details as a cautionary tale. Rather than a Frankensteined patchwork of past and present, Transit is altogether something unique, in the same way that Fahrenheit 451 created a warning about where Ray Bradbury saw 1950s culture going—using familiar, but not directly referential, though at times dissonant, pieces of our world. Similarly, science-fiction author Philip K. Dick created a fascinating what-if scenario in The Man in the High Castle, which linked the past and present by exploring a North America divided between Nazi Germany and Imperialist Japan. Like those examples, Petzold seems to create a singular world that inhabits its own continuum, and within that, he evokes familiar signs of our past and present, while conforming to specifics of neither. Ultimately, he asks where we’re going as a world culture, forward or backward, and in the end, he provides a sardonic answer with his use of the Talking Heads song “Road to Nowhere” over the final credits. Through Petzold’s observations and thoughtful approach, Transit’s power as a metaphor remains just as engaging as the affecting melodrama at its center.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review