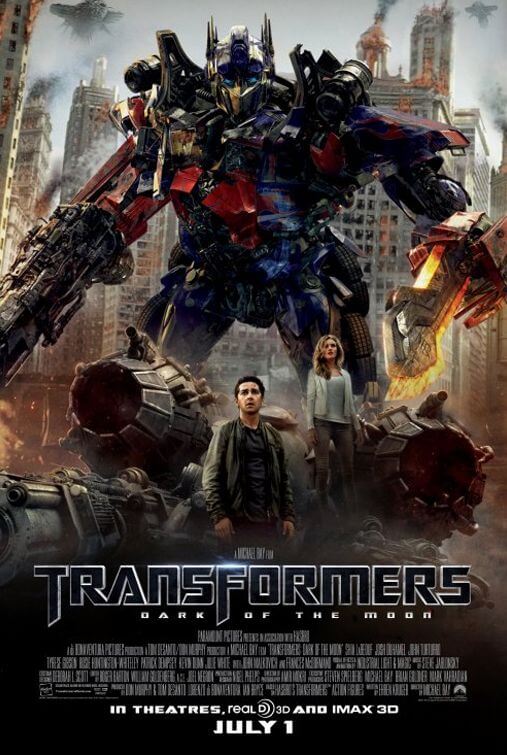

Transformers: Dark of the Moon

By Brian Eggert |

For two hours and thirty-four minutes, Michael Bay’s Transformers: Dark of the Moon launches an assault on the human brain, testing its resilience to ridiculous storytelling and disjointed editing. Most viewers will recognize Bay’s ability to assemble endless explosions, loud noises, and a barrage of inelegant colliding metal robots, many of which are impossible to tell apart during the fracas. Moviegoers will react one of two ways to Bay’s product: either (1) their brains will shut down, allowing for a primitive reaction to attention-grabbing sounds and images, resulting in the illusion of enjoyment; or (2) the moviegoer’s brain will shut down, as the apparent lack of anything intelligent onscreen causes an automatic blackout period, until the end credits begin to roll and the moviegoer awakens with a sense of “what just happened?” Either way, the moviegoer’s brain must shut down.

This comes after Bay’s voiced admittance that his previous entry, Revenge of the Fallen, was not everything he wanted it to be, an outcome on which he blamed the writer’s strike and seemed determined to improve upon. Ehren Kruger, credited screenwriter for the first sequel to 2007’s Transformers, returns to Dark of the Moon with just as much disjointed logic and as many unnecessary subplots as its immediate predecessor. Given the result and its almost universal panning by critics, it won’t be long before Bay realizes Kruger isn’t necessary and punches out some negligible dialogue himself to accompany his usual array of clashing robots and gratuitous lens-humping of his lead actress (courtesy of Megan Fox’s replacement Rosie Huntington-Whiteley, whose butt is the centerpiece to a long tracking close-up).

Opening in the 1960s, the movie suggests an alternate history—that the Space Race began when NASA recorded an unidentified craft crash-landing on the moon. Americans first arrived to investigate with Apollo 11 and discovered the first evidence of Transformers, which was kept secret for decades. As it turns out, on the craft was Sentinel Prime (voice of Leonard Nimoy), an Autobot leader and inventor of their greatest weapon, which, in the present day, the evil Decepticons are after to use against the Autobots. Throughout the course of the movie, Decepticons, led by Megatron (voice of Hugo Weaving), scheme to gather components of the weapon and use it to turn humanity into a labor force to rebuild their home planet, Cybertron. The movie’s last hour involves a Decepticon attack on Chicago and recalls a Japanese monster movie, with ant-like humans shouting and pointing at the invading alien army, while powerful bad guys treat national landmarks like cardboard miniatures.

But the above description explains merely the basic conflict. Bay and Kruger also cram an excess of subplots, oodles of pointless exposition, and battles that just keep going and going into the overlong running time. Ousted by the government and looking for a new job, Sam Witwicky (Shia LaBeouf) struggles to keep his new girlfriend, Carly (Huntington-Whiteley), away from her rich and charismatic boss, Dylan (Patrick Dempsey, who, it turns out, is not a robot). At the same time, Sam learns about a Decepticon plot and tries to warn the Autobots, but hard-nosed government suit Mearing (Frances McDormand) says he doesn’t have clearance. But then Carly gets upset because Sam is more interested in the world possibly ending than their relationship, so off she goes to cry on Dylan’s shoulder. Josh Duhamel and Tyrese Gibson reprise their roles as soldiers; the less said about them the better. And eventually, Mearing resolves to detach the U.S. from Transformers altogether by blasting the Autobots into space.

The whole movie is a practice in uneconomic storytelling. Did audiences really need a subplot about Sam finding a job, or was that just an excuse to bring his parents (Kevin Dunn and Julie White) back into the fray for a lecture about the state of Sam’s life, followed by an applying-for-a-job montage? Much like Revenge of the Fallen, several characters are dedicated to comic relief, whereas most blockbusters need only one. Sam’s parents, John Turturro’s blathering fanatic FBI agent, John Malkovich’s anal retentive boss, Ken Jeong’s annoying office worker, Alan Tudyk’s German helper-monkey, and plenty of jabbering robots (with decidedly less offensive racial stereotypes than those in Revenge of the Fallen) force unfunny humor on the audience, contradicting Bay’s intended seriousness for a desired “epic” approach.

Indeed, Bay imparts what he believes is of grave importance to the material by exploiting American tragedies and thrashing national monuments for the sake of action. A gloating Megatron takes his place atop a decapitated Lincoln Memorial, while his mini-robot lackey scrapes at Lincoln’s fallen head; images of Chicago’s skyscrapers toppling evokes 9/11, as does intentional lingo like “Ground Zero” and “let’s roll.” Bay employed the same tricks on Pearl Harbor—a film about one of America’s most devastating moments, which Bay infused with the dramatic weight of a paper clip—and in both cases, his usage of ponderous close-ups and heavy music is as transparent as it is emotionally vapid. As a result, LaBeouf’s ridiculous performance (a display of varying screams of panic and desperation) proves unintentionally funny.

Admittedly, somewhere between flying squirrel parachuters and Sam playing rodeo with a Decepticon, I lost track and stopped caring. Random battles during Chicago’s takeover occur without much reason or connectedness from one scene to the next. Bay seems to be saying, “here’s a battle,” and “oh, here’s another battle,” and “one last battle for you,” and then, “just kidding, there are about ten more battles.” And after a pair of these rock-em-sock-em robots have finished destroying each other, the victor delivers a line like “class dismissed,” and the audience wonders if they missed some ongoing schooling quips throughout the fight, but they have not. This is not filmmaking; this is stringing together action setups. Typically, editing is supposed to connect one shot to the next, but Bay’s three credited editors (!) have thrown such a straightforward approach out the window and resolved to bring incoherence from scene to scene. Cuts average at one every five-to-eight seconds, as opposed to Bay’s usual cut every three-to-five seconds—the extra time added to maximize shot retention for his use of 3-D stereoscopic lenses. Even with these additional seconds, Bay’s production still feels like a nearly three-hour commercial, complete with product placements galore.

Once upon a time, Bay had shunned the use of 3-D, but who can believe anything this man has to say? After Revenge of the Fallen, he and 2012 director Roland Emmerich also promised to each make a smaller, more personal picture. Emmerich’s period piece drama Anonymous, about the origins of Shakespeare, opens in the fall. But instead of following through with a small passion project, Bay destroyed Chicago. Prescreenings of the film were only available in 3-D, so I didn’t bother. This review is based on a 2-D screening, in which action scenes were at times unintelligible blurs of CGI nonsense, good and bad robots indecipherable from each other until Bay’s overwrought uses of slow-motion allowed our eyes to catch up. I can’t imagine what they would have looked like in color-muddying 3-D.

Transformer aficionados will no doubt make many apologies for Dark of the Moon and find it entertaining; using Revenge of the Fallen as their most recent basis of comparison, who can blame them? To be fair, there are one or two visually impressive moments in the movie (Bay has always had an eye for shot composition), as well as unabashed reverence for Leonard Nimoy. Along with Nimoy’s voice talents come a number of Star Trek references, including a clip from the episode “Amok Time” and Nimoy delivering his Wrath of Khan line, “The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few”—albeit twisted into nonsensical context here since there are fewer Transformers than humans. But moments of geekdom aside, Bay’s direction and the script are chaotic and unfocused, challenging attentive viewers to find cohesion where there is none. Now that Bay has completed his trilogy, here’s hoping he steps away, leaving Paramount’s franchise to a filmmaker concerned as much with story as they are with blowing stuff up.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review