Toy Story 4

By Brian Eggert |

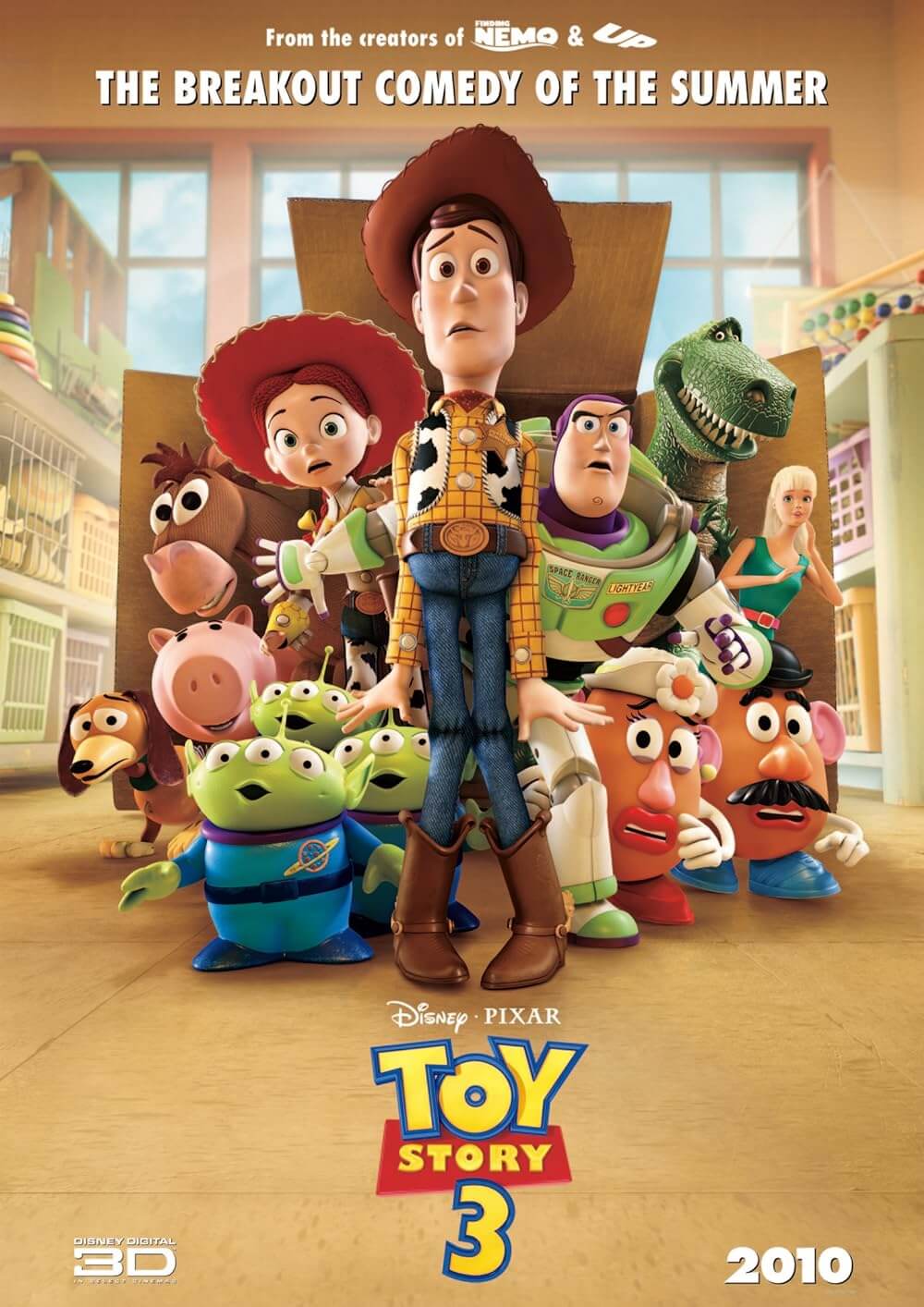

A certain level of dread accompanies the initial viewing of Toy Story 4, Pixar’s latest addition to their most popular and beloved franchise. The animation studio’s creative team, including John Lasseter, Andrew Stanton, and Lee Unkrich, already brought the series to a satisfying conclusion with Toy Story 3 in 2010. In that film, the toys’ owner Andy, who grew up over the course of three Toy Story entries and fifteen years, donated his box of treasured figures—Sheriff Woody (Tom Hanks), Buzz Lightyear (Tim Allen), rootin’ tootin’ calamity Jessie (Joan Cusack), and the others—to Bonnie (Madeleine McGraw), a young preschool-age neighbor. After an existential crisis that resolved itself with a powerful conclusion, the toys accepted their lot. Somehow, Toy Story 3 said everything there was to say about being a child and needing a toy for comfort, while also underscoring the selfless métier of action figures, stuffed dolls, plastic dinosaurs, remote control cars, and all the rest. With this lesson learned and the trilogy brought to a close, one cannot help but approach Toy Story 4 with suspicion. What else could Pixar have to say?

In the same way that Woody and his pals cannot stop being the best toys they can be, the folks at Pixar cannot help but return to these characters. But Toy Story 4 is self-reflective, in that the narrative trajectory of this third sequel seems to remark directly on Pixar’s persistent need to provide children with what they need—hours of entertainment, imagination, emotional lessons, and enduring friendship—through the Toy Story characters. The film is an apt metaphor for its creation. With story contributions from eight credited writers and a screenplay by Stanton and Stephany Folsom—Pixar is the only Hollywood studio that actually works better with more writers—Toy Story 4 acknowledges, through Woody, that the series has carried on too long. Now a bottom-tier toy in Bonnie’s inventory, which is overseen by the mayoral plush Dolly (Bonnie Hunt), Woody realizes that his new role may simply be that he’s no longer necessary. Though he’s not being played with, which is every toy’s delight, he can nonetheless ensure Bonnie’s happiness by a different act of selflessness: enabling Bonnie’s latest and greatest acquisition.

This is where Toy Story 4 gets weird, albeit in a good way. After trying to help Bonnie on orientation day before kindergarten by supplying her with various arts and crafts from the wastebasket, Woody becomes a pseudo-Frankenstein in the creation of Sporky (Tony Hale). Made by Bonnie with a spork torso and head, pipe-cleaner arms, popsicle stick feet, Play-Doh mouth, and googly eyes, Sporky was born from trash and wants to return to trash. He doesn’t have the innate desire to supply his owner with hours of joy; he’s a mindless being, often hilariously so, and seems to know he shouldn’t exist (viewers familiar with Hale’s Buster Bluth from Arrested Development will recognize the perfect voice casting). Much of the humor around Sporky involves his morbid streak of self-destruction, his desire to return to the comforting trash can. But for the moment Bonnie loves Sporky more than any of her other toys, and so Woody’s new role becomes making sure that Sporky doesn’t leap into the garbage, where he feels most at home, and instead learns the value of being a toy.

Woody’s mission becomes complicated when Sporky leaps from the family RV during a road trip vacation to a small town equipped with a carnival and antique shop. Lost on the road and trying to reconnect with Bonnie and the other toys, Woody and Sporky wander until they notice, in the antique shop window, the lamp that once belonged to Bo Peep (Annie Potts), who was curiously missing from Toy Story 3. In a prologue, the third sequel establishes that Bo Peep was given away by Andy’s sister years ago, just as she and Woody were on the cusp of a developing romance. Now, fate would seem to have given Woody and Bo Peep another chance. But when Woody and Sporky enter the store to find her, they’re confronted by Gabby Gabby (Christina Hendricks), a Chatty Cathy-esque doll who has apparently gone mad (if the music from The Shining is any indication) from not being played with for decades. Gabby believes she hasn’t been purchased because her voice device is broken, and so she resolves to cut Woody’s working voicebox from his back. If that concept isn’t scary enough, she’s joined by several ventriloquist-dummy soldiers who recall the insidious doll Fats from Magic (1978).

But Toy Story 4’s willingness to go to strange and dark places is part of its charm. Back at the RV, the other toys attempt to mount a rescue headed by Buzz, who receives some sage advice from Woody to listen to his “inner voice,” and the dimwitted Buzz interprets this as the voice buttons on his chest, which comically takes the place of his conscience in several situations. Elsewhere, Jordan Peele and Keegan-Michael Key lend their voices to Bunny and Ducky, carnival prize giveaways and cheaply made plush animals with overactive imaginations. Some of the film’s heartiest laughs arise from seeing Bunny and Ducky’s increasingly outlandish and elaborate plans to resolve the conflict—most of which involve attacking humans. Other goofy additions are Duke Caboom (Keanu Reeves), a Canadian stuntman figure on a wind-up motorcycle, and the hyperactive Polly Pocket-like Giggle McDimples (Ally Maki).

If there’s a potential misstep in Toy Story 4, it’s the screenplay’s uncharacteristic resolution that suggests a toy could have a life without a child. When Woody finally reconnects with Bo Peep, he discovers she’s been “free” for several years, having established a renegade survivor existence alongside her porcelain sheep Billy, Goat, and Gruff, whom she drives around in a remote-controlled skunk to scare away humans. As Woody warms to the idea of living out his days with Bo Peep and existing without a child, the notion betrays the ideal established by the three previous Toy Story films. One could suppose this narrative arc answers the question, What happens to unwanted or lost toys? by suggesting the romantic idea that they’re out there somewhere, living happy and fulfilled lives. But it’s a notion that potentially spoils the conclusion established by Toy Story 3 by questioning the purpose of toydom itself. Then again, perhaps such questions are healthy.

Holding any grudge against Toy Story 4 is an exercise in sheer stubbornness and, perhaps, a limited view of the series and the integrity of the characters. This is clearly the funniest and most fast-paced entry in the series, and first-time Pixar director Josh Cooley, who contributed to the screenplay of Inside Out (2015), keeps things deliriously entertaining. As characters zip from one perilous situation to another, the oddball personalities of Sporky, the borderline nightmarish presence of Gabby and her dummies, and the consistently hilarious Bunny and Ducky, keep us laughing or gasping. Pixar, as ever, knows how to negotiate the viewer between emotional highs and lows, making us feel like we’ve been through a journey when it’s all over. Of course, Toy Story 4 is also incredibly animated. Pay particular attention to the antique shop’s glass cases, the kaleidoscopic carnival ride lights, and the photoreal quality of rainfall and nature scenes. No other computer animation house comes close to the visual beauty of Pixar’s output.

Holding any grudge against Toy Story 4 is an exercise in sheer stubbornness and, perhaps, a limited view of the series and the integrity of the characters. This is clearly the funniest and most fast-paced entry in the series, and first-time Pixar director Josh Cooley, who contributed to the screenplay of Inside Out (2015), keeps things deliriously entertaining. As characters zip from one perilous situation to another, the oddball personalities of Sporky, the borderline nightmarish presence of Gabby and her dummies, and the consistently hilarious Bunny and Ducky, keep us laughing or gasping. Pixar, as ever, knows how to negotiate the viewer between emotional highs and lows, making us feel like we’ve been through a journey when it’s all over. Of course, Toy Story 4 is also incredibly animated. Pay particular attention to the antique shop’s glass cases, the kaleidoscopic carnival ride lights, and the photoreal quality of rainfall and nature scenes. No other computer animation house comes close to the visual beauty of Pixar’s output.

Audiences will be hard-pressed to find a better, G-rated family adventure in the summer of 2019, especially one that clocks in at just 100 minutes in this age of bloated blockbusters. And though fans of the entire series may question the fate of Woody and Bo Peep, and how that figures into the arc of the whole series, the filmmakers acknowledge the future’s uncertainty in Toy Story 4 with a final, rather philosophical coda. Much of the film has a theme that ponders and pointedly questions the nature of existence for a toy. Maybe this is Pixar’s way of challenging assigned roles, disrupting the status quo, and suggesting that an alternative lifestyle may be preferable, if that’s your thing. In any case, these are high-minded concepts for an animated film, even one as thrilling, hilarious, and beautifully animated as this. But isn’t that what places Pixar at the top of all modern animation studios, their willingness to approach storytelling unconventionally and with a thought-provoking depth?

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review