Toy Story 2

By Brian Eggert |

Talk of a sequel began immediately after the release of Toy Story in 1995, once it was evident that Pixar Animation Studios had made the first fully computer-animated film a hit. The sequel was initially planned as a direct-to-video release, following Disney’s discovery that a lucrative business exists in hugely profitable but cheaply produced titles like The Return of Jafar, the video sequel to Aladdin. Much of Pixar’s staff was already hard at work on their next feature, A Bug’s Life, and so the production of Toy Story 2 was ostensibly a side-project, placed in another building separate from the principal Pixar staff. But as audiences now expect from the studio, Pixar surprised everyone and turned out a film that surpassed typical direct-to-video quality, making what was, as some critics assessed, a richer film than its predecessor.

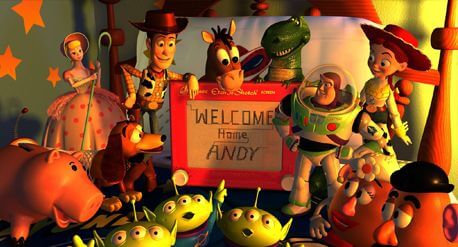

In brainstorming for story ideas, director John Lasseter pondered what the worst fear of a toy would be. He already posited in the first film that bliss for a toy is being played with. And so the opposite, being kept merely on display, or worse—gulp!—kept mint in the package, would be a toy’s nightmare. From that concept, along with the addition of a villainous toy collector idea that was scrapped from story discussions for the first film, the scenario for the sequel was born. The story would follow Woody, (voice of Tom Hanks), a vintage cowboy doll after he’s stolen by the seedy toy collector Al (voice of Wayne Knight) to complete a classic memorabilia collection that he intends to sell. Woody discovers he’s the main character from a 1950s-era television show called Woody’s Roundup, something akin to Howdy Doody and Hopalong Cassidy programs. Meanwhile, Buzz Lightyear (voice of Tim Allen) and the gang attempt to locate and rescue Woody, only to find he wants to stay in Al’s collection.

Along with this involved plot, new toy characters are introduced, including the wild cowgirl Jessie (voice of Joan Cusack) and Stinky Pete, the Prospector (voice of Kelsey Grammer). Both were based on the type of characters that traditionally appear in early Western television shows. Jessie comes from the rather obvious deficiency of any strong female characters in the first film, a criticism that was mildly present in the film’s reviews. Lasster’s wife suggested a female character for girls, but one not identified by her sex (unlike Bo Peep). Jessie, who in an early script draft used her feminine wiles to convince Woody to stay in their toy collection, was changed to an Annie Oakley figure, complete with an adventurous spirit and tragic past that represents the heart of the film.

Along with this involved plot, new toy characters are introduced, including the wild cowgirl Jessie (voice of Joan Cusack) and Stinky Pete, the Prospector (voice of Kelsey Grammer). Both were based on the type of characters that traditionally appear in early Western television shows. Jessie comes from the rather obvious deficiency of any strong female characters in the first film, a criticism that was mildly present in the film’s reviews. Lasster’s wife suggested a female character for girls, but one not identified by her sex (unlike Bo Peep). Jessie, who in an early script draft used her feminine wiles to convince Woody to stay in their toy collection, was changed to an Annie Oakley figure, complete with an adventurous spirit and tragic past that represents the heart of the film.

When Disney execs screened some early footage, the result was deemed cinema-worthy. And despite an earlier press release that announced the sequel would be direct-to-video, Disney agreed to distribute the picture theatrically. In a renegotiation of their contract with Disney, Pixar determined that the two companies would split the costs and the profits for the release down the middle. However, there was only a short time (less than a year) until the proposed release date, and the upgrade to a theatrical release meant an increased runtime, up from the typically brief mini-feature mode of Disney’s direct-to-video output. Lasseter oversaw the additions to the story, so as not to make the supplementary footage seem like padding. The Buzz Lightyear video game sequence in the film’s opening, as well as Woody’s nightmare about being abandoned by his owner Andy, were added to the story and meshed flawlessly with the final product.

Unselfishly, though he remained in control of the production in a creative sense, Lasseter wanted to explore new directing talent, though he had directed Toy Story. The other obvious choices in Pixar were busy on their own projects—Andrew Stanton had been developing A Bug’s Life, while Pete Docter was in the preliminary stages of Monsters, Inc. And so Lasseter chose Ash Brannon to co-direct and later added Lee Unkrich (helmer of Toy Story 3) to the production as well. Still, during production, Lasseter obsessively cut scenes and demanded certain characters’ expressions be altered for a particular moment. These changes were made on completed animation sequences, whereas traditionally animated films are pre-edited and pre-planned before animation to such a degree that post-production editing is unnecessary. But because Lasseter was overseeing several aspects of Pixar’s production, with one hundred percent of his time not on Toy Story 2, he was not there to notice the need for these necessary changes earlier.

What’s more, with less than a year to finish their now-longer film, animators worked long hours to meet their deadlines. Pixar did not encourage its employees to overwork themselves, and in some cases limited overtime for its employees, particularly after one tired animator forgot to drop off his infant child at daycare, leaving it in the back seat of his car. Although the child was unharmed, the incident made Pixar even more aware of how thinly stretched their staff was. Nevertheless, their deadline remained, and because president Steve Jobs had already secured promotional and toy merchandising deals in step with the November 24 release date, the deadline was impossible to extend.

What’s more, with less than a year to finish their now-longer film, animators worked long hours to meet their deadlines. Pixar did not encourage its employees to overwork themselves, and in some cases limited overtime for its employees, particularly after one tired animator forgot to drop off his infant child at daycare, leaving it in the back seat of his car. Although the child was unharmed, the incident made Pixar even more aware of how thinly stretched their staff was. Nevertheless, their deadline remained, and because president Steve Jobs had already secured promotional and toy merchandising deals in step with the November 24 release date, the deadline was impossible to extend.

Regardless of being overworked, the artistry behind the film is evident in every frame and greatly improves on the original in terms of lighting, textures, and facial expressions. Characters were given more facial controls to make their expressions more lifelike. And the animators cleverly used existing digital models—completed for Toy Story, A Bug’s Life, or the company’s short films—to fill out certain scenes. A Bug’s Life’s Ant Island, the secluded patch of land from which a lifelike tree springs, was reformatted for the tree where Jessie has her fondest memories of her former owner. The alien planet in the Buzz Lightyear videogame was also derived from Ant Island. The toy cleaner hired by Al to reassemble the very used Woody doll was merely the chess-playing Geri from Pixar’s Oscar-winning short Geri’s Game. While these appearances were initially used to cut costs, such in-film references to other Pixar material would become standard practice in their films, except, later on, it was done just for the fun of it.

The film grossed $245 million domestically and $486 million worldwide, leaving Pixar with yet another hit and a sense of secured financial footing—something which the company had struggled with up to this point. The reviews were raving, as most critics had decided that Toy Story 2 was a better film than Toy Story. It’s easy to understand why critics thought as much, as the sequel seems to enliven every character, adding depth and artistic layers to every scene. In terms of artistry alone, there’s no question, the sequel far exceeds the original. As technology improves and Pixar animators gain more experience, the visual outcome can only get better. Every next Pixar film would show gradual to extreme improvements from a visual standpoint: Monsters, Inc. would have audiences floored at the detail in the monsters’ fur. Finding Nemo would do wonders with bright oceanic colors and underwater lighting. The Incredibles would finally achieve believable (though highly stylized) human characters, something the company had struggled with in earlier films. Ratatouille would make the audience’s collective mouths water with its lifelike gourmet food. And WALL·E’s incredible character design would have us falling in love with seemingly lifeless robots.

But visual superiority does not automatically infer a better film. The animation in Cars, for example, far exceeds the animation in some of its predecessors; however, it remains the least engaging Pixar film narratively speaking. Toy Story holds superiority over its sequel for its singularity of purpose, its originality, and its effortlessness. Whereas Toy Story 2, while being a delightful and moving film, offers perhaps too many sequel moments that nod to jokes made in the first. Moreover, songwriter Randy Newman, who wrote and performed the music for the first film, doesn’t lend his signature voice to the soundtrack, in spite of writing the songs. Then-popular singer Sarah McLachlan performs the film’s heartening ballad “When Somebody Loves You”, and though Hanks happily sings “You’ve Got a Friend in Me” in an episode of Woody’s Roundup, the lacking presence of Newman’s chummy voice is felt whenever someone else is singing his music.

But visual superiority does not automatically infer a better film. The animation in Cars, for example, far exceeds the animation in some of its predecessors; however, it remains the least engaging Pixar film narratively speaking. Toy Story holds superiority over its sequel for its singularity of purpose, its originality, and its effortlessness. Whereas Toy Story 2, while being a delightful and moving film, offers perhaps too many sequel moments that nod to jokes made in the first. Moreover, songwriter Randy Newman, who wrote and performed the music for the first film, doesn’t lend his signature voice to the soundtrack, in spite of writing the songs. Then-popular singer Sarah McLachlan performs the film’s heartening ballad “When Somebody Loves You”, and though Hanks happily sings “You’ve Got a Friend in Me” in an episode of Woody’s Roundup, the lacking presence of Newman’s chummy voice is felt whenever someone else is singing his music.

Quibbles aside, Toy Story 2 sends audiences into an unforgettable world that may be made of plastics, but it nevertheless exudes significant emotion and crackles with comical wit. The endearing characters feel three-dimensional without the benefit of 3-D glasses, not only because of Pixar’s incredible animation, but because the voice actors capture their roles so absolutely. Immersed in this world, we can’t imagine how any Pixar film could be deemed suitable for a direct-to-video release. That Pixar’s films, even back-end projects like this one, contain cinematic airs, while Disney has resolved to release a greater number of sloppy titles on home video than in the theater, speaks to the Pixar staff’s enduring talent as animators and storytellers.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review