Total Recall

By Brian Eggert |

A gruesome but boldly imagined piece of science-fiction, Total Recall offers no end of rewarding contradictions in the mode and treatment of its story, being both a sheer adrenaline rush and a thoughtful, even existential questioning of reality. Based (although “inspired by” is more appropriate) on legendary author Philip K. Dick’s short story “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale” and adapted by Alien co-writers Dan O’Bannon and Ronald Shusett, this spectacle of big ideas doused in machine gun carnage is realized by director Paul Verhoeven, who explored similar themes and contradictions with Robocop in 1987. And like that film, Verhoeven’s kinetic, aggressive style of filmmaking is offset by his winking satire that has a wildly enjoyable manner, but with an outcome that leaves the viewer, much to their surprise, contemplating what it all means. Described by O’Bannon and Shusett as “Raiders of the Lost Ark on Mars,” this gross oversimplification doesn’t quite sum up what a raucous, clever piece of entertainment Verhoeven and company released on the world in 1990.

Certainly, the presence of leading man Arnold Schwarzenegger alone will forever dissuade some viewers from taking Total Recall seriously. After all, so much of Verhoeven’s production seems to distract from the rather brainy scenario that unfolds, Schwarzenegger’s presence most of all. There’s intentional camp humor, glib one-liners, a massive body count, gallons of blood, endless gunfire, grotesque eye-popping makeup, seamless early CGI, wowing practical special FX, and a conspicuous degree of equal parts freakshow and 1990s sex appeal to distract us. Operating at the same time as these raw factors, however, is a smart Dickian world of altered states, monopolistic corporations, and “know thyself” identity crises, wrapped up together in a slick spy yarn and alien conspiracy. So many plot elements are running through the film that it’s any wonder how Verhoeven manages not to completely lose his audience and also deliver such an entertaining piece of blockbuster filmmaking—but he does it.

The film arrived in theaters at the height of Schwarzenegger’s career, just six months after his biggest hit yet, the comedy Twins, and six months before another ironic comedy, Kindergarten Cop. For audiences accustomed to the Austrian musclebag’s usual R-rated actioners (Conan the Barbarian, The Terminator, Predator, et al.), his sudden pop-culture phenomenon had begun to tap a whole new family-friendly market. And yet, amid this career shift, Schwarzenegger pursued Mario Kassar and Andrew Vajna’s Carolco Pictures to purchase the film rights and existing screenplay drafts from the ailing De Laurentiis Entertainment Group, whose own science-fiction track record with David Lynch’s grand flop based on Frank Herbert’s Dune put the studio off the genre. With creative control over his director and crew, Schwarzenegger negotiated a huge payday and a sizeable chunk of the profits, while demanding Dutch filmmaker Paul Verhoeven at the helm. But rather than exploit his sudden appeal as a self-parodying comedy star, this beefcake performer helped arrange a film that remains a contradiction as the goriest yet most intelligent picture the actor would ever be involved in.

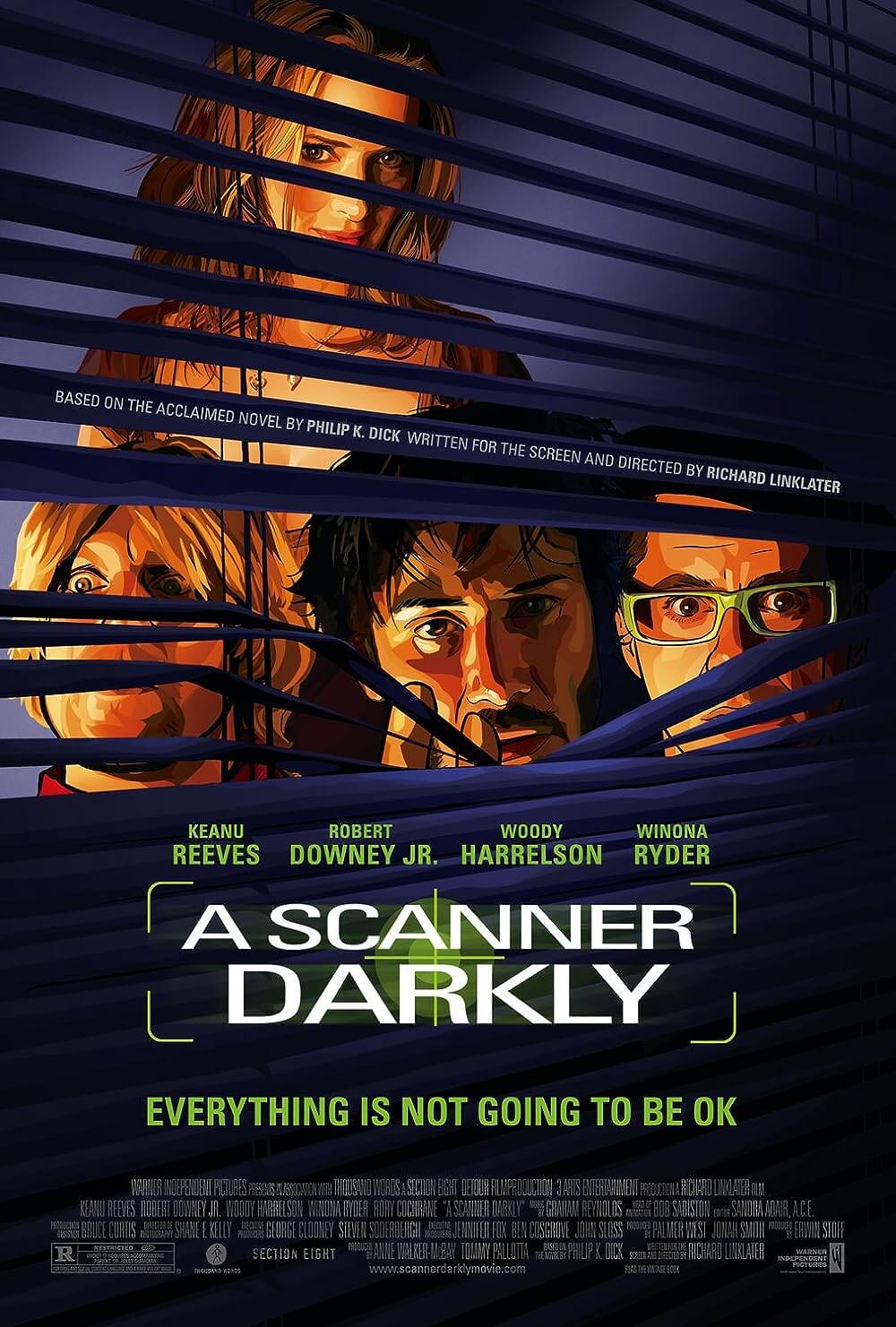

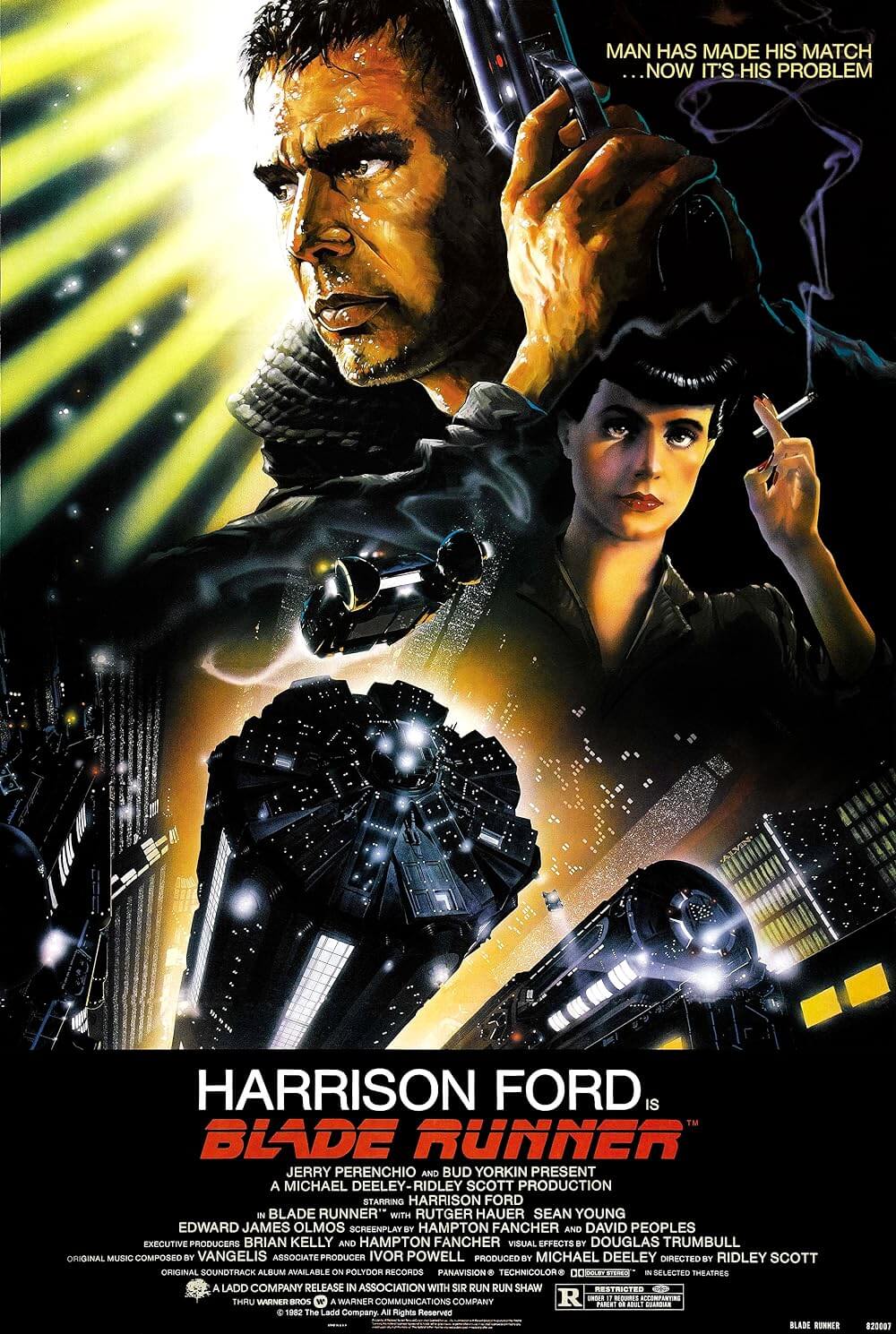

Long before Carolco or Schwarzenegger’s involvement, O’Bannon and Shusett purchased the rights to Dick’s story from the author himself in 1974, and like Blade Runner, it would be a book-to-film adaptation that Dick would never see come to fruition during his lifetime. For years, the screenwriters shopped their project to various studios until De Laurentiis picked it up, and eventually hired David Cronenberg to direct as a follow-up to 1983’s The Dead Zone. Cronenberg spent a year retooling and rewriting with O’Bannon and Shusett, resulting in countless drafts, none of which pleased the would-be director, writers, or producers. Cronenberg left the production to make The Fly, while his considerable creative contributions, such as the mutant underground active on Mars, received no screen credit. Inspired to be faithful to a Dickian tone, Cronenberg’s vision would have featured leading man William Hurt (of whom the producers did not approve) in a twisting, but decidedly less actionized scenario. Not until 1999, when Cronenberg released the very Dickian sci-fi mind-bender eXistenZ would audiences glimpse what his version of Total Recall may have been like. The fast-paced, rollercoaster experience O’Bannon and Shusett ultimately conceived, aided by latecomer and credited co-writer Gary Goldman (Big Trouble in Little China), is not necessarily better or worse than what might’ve been Cronenberg’s headier approach, but it’s certainly not Cronenbergian.

Long before Carolco or Schwarzenegger’s involvement, O’Bannon and Shusett purchased the rights to Dick’s story from the author himself in 1974, and like Blade Runner, it would be a book-to-film adaptation that Dick would never see come to fruition during his lifetime. For years, the screenwriters shopped their project to various studios until De Laurentiis picked it up, and eventually hired David Cronenberg to direct as a follow-up to 1983’s The Dead Zone. Cronenberg spent a year retooling and rewriting with O’Bannon and Shusett, resulting in countless drafts, none of which pleased the would-be director, writers, or producers. Cronenberg left the production to make The Fly, while his considerable creative contributions, such as the mutant underground active on Mars, received no screen credit. Inspired to be faithful to a Dickian tone, Cronenberg’s vision would have featured leading man William Hurt (of whom the producers did not approve) in a twisting, but decidedly less actionized scenario. Not until 1999, when Cronenberg released the very Dickian sci-fi mind-bender eXistenZ would audiences glimpse what his version of Total Recall may have been like. The fast-paced, rollercoaster experience O’Bannon and Shusett ultimately conceived, aided by latecomer and credited co-writer Gary Goldman (Big Trouble in Little China), is not necessarily better or worse than what might’ve been Cronenberg’s headier approach, but it’s certainly not Cronenbergian.

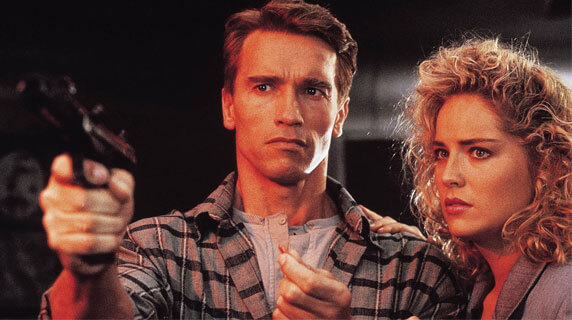

In Verhoeven’s film, Schwarzenegger plays Douglas Quaid, an Earthbound construction worker whose troubling nightmares about Mars haunt his sleep, much to the annoyance of his trophy wife, Lori (Sharon Stone). Background newscasts relay the upsetting state of the Mars colony in this 2084 setting, where a mutant underground battles against a dictatorial governor Vilos Cohaagen (Ronny Cox), for access to an alien artifact, resulting in violence in the streets. Quaid wants to visit this hotspot for a romantic getaway, but Lori doesn’t see the appeal. Instead, Quaid resolves to visit Rekall, Inc., a company that implants vacation memories for a fractional cost of the real thing. Quaid wants the standard Mars package, while the smarmy salesman pitches an “Ego Trip,” which offers the customer a vacation from themselves. Quaid agrees to a secret agent profile, complete with a damsel to rescue, a planet to save, and an alien conspiracy to uncover. Trouble is, as the technicians begin the implantation process, they find Quaid’s mind has already been tampered with. All at once, Quaid squirms violently in his restraints and screams out about his cover being blown, as though he’s actually been to Mars and is actually a secret agent. But is this the case, or is this all part of the implant? The editing cleverly maneuvers around what exactly happens here. Whether or not Douglas Quaid is, in fact, an undercover spy remains a mystery to be decided by the viewer, and because this unknown is never answered within the film, its consequence brings us back to the story time and again.

Whether it’s an implanted fantasy or reality finally taking over, Quaid returns home to find his life is merely a deep cover dream, his significant other a hired goon watching over him. With Cohaagen’s top hound Richter (Michael Ironside) trailing close behind, Quaid heads to Mars for answers and finds them in a sleazy brothel, where a former fling he no longer remembers, Melina (Rachel Ticotin, also Quaid’s fantasy girl from Rekall), insists he’s a member of the resistance. The underground wants Cohaagen to release rumored alien technology to give Mars free, breathable fresh air by creating an atmosphere, but Cohaagen makes money by supplying the planet with his artificially generated air, so he attempts to bury the rumors and resistance. Of course, Cohaagen’s crew claims Quaid is actually working for them to infiltrate the mutant underground, while Quaid doesn’t know who or what to believe—so why not believe himself? To convince him, Cohaagen shows Quaid, who is supposedly a Cohaagen agent named Hauser, a video Quaid recorded of himself as Hauser before this headache began. Nevertheless, Quaid likes being the underdog hero and resolves to save the day.

Whether it’s an implanted fantasy or reality finally taking over, Quaid returns home to find his life is merely a deep cover dream, his significant other a hired goon watching over him. With Cohaagen’s top hound Richter (Michael Ironside) trailing close behind, Quaid heads to Mars for answers and finds them in a sleazy brothel, where a former fling he no longer remembers, Melina (Rachel Ticotin, also Quaid’s fantasy girl from Rekall), insists he’s a member of the resistance. The underground wants Cohaagen to release rumored alien technology to give Mars free, breathable fresh air by creating an atmosphere, but Cohaagen makes money by supplying the planet with his artificially generated air, so he attempts to bury the rumors and resistance. Of course, Cohaagen’s crew claims Quaid is actually working for them to infiltrate the mutant underground, while Quaid doesn’t know who or what to believe—so why not believe himself? To convince him, Cohaagen shows Quaid, who is supposedly a Cohaagen agent named Hauser, a video Quaid recorded of himself as Hauser before this headache began. Nevertheless, Quaid likes being the underdog hero and resolves to save the day.

At one point mid-film, a character named Dr. Edgemar (Roy Brocksmith) appears and claims this entire experience is taking place inside Quaid’s head, and that Quaid has lost himself in his Rekall fantasy: “Are you afraid to admit that you’re having a schizo-paranoid episode? Or are you really convinced that you’re an invincible secret agent from Mars, who is in the middle of an interplanetary conspiracy to make him think that he’s a lowly construction worker?” He tries to sway Quaid to take a pill that, in his unconscious mind, represents Quaid’s desire to return to reality. Now we begin thinking about how everything in the film has played out exactly as his Ego Trip package promised, with details fuelled by the morning news. Still suspicious, Quaid notices sweat on the doctor’s brow and fires a bullet into his head, and now reality comes “crashing down” just as Edgemar promised. Or, is this just an elaborate rouse orchestrated by Cohaagen to catch Quaid—or is it Hauser?—off guard? Verhoeven refuses to give the audience an easy answer. In the final scene where Quaid and Melina celebrate their victory with a kiss, the backdrop overlooking the now blue-sky Martian landscape, the moment fades to white. Jerry Goldsmith’s excellent score turns from a victorious pounding to a light, apprehensive glimmer of notes that prompt the audience to speculate if perhaps Quaid is back at Rekall being lobotomized.

Schwarzenegger has more than his fair share of one-liners, which may cheapen the material for highbrow viewers, while also lending a particular comic camp value to the ostentatious proceedings. When Lori fails at killing Quaid, she pleads with him. “You wouldn’t hurt me, would you, sweetheart? …After all, we’re married.” Quaid responds by shooting her in the head: “Consider that a divorce.” But then again, aren’t moments like these exactly the point of a Rekall-programmed escape? Do Quaid’s fantasies or the promise of the “Ego Trip” not assign him a certain inhumanly heroic persona, since at first Quaid is an everyman construction worker and terminal daydreamer who wishes his life was more adventurous? As a result, this futuristic Walter Mitty commits to his heroic “role” by occupying the associated James Bond-esque characteristics. Consider then how his corny one-liners might only be a product of a man so engulfed by his fantasy that he loses himself in the performance. So, when Schwarzenegger uses a massive drill to puncture the double-crossing mutant Benny and shouts, “You’re screwed!,” think of it not as Hollywood at its action movie worst, but instead consider how moments like these fit nicely into the fabric of Quaid’s desired fantasy, and thus into the overall narrative schematic. Whereas standard Schwarzenegger fare becomes an instant guilty pleasure from his cliché use of such action movie tropes, with Total Recall, the filmmakers have created a justifiable reason for Quaid’s (and thus Schwarzenegger’s) use of tongue-in-cheek humor, eliminating any requirement to justify the film by downgrading it to a guilty pleasure.

While we ask ourselves questions about the head games being played on us, Verhoeven supplies a relentless pace and thrilling but oh-so-bloody violence amid the twists and turns. The director’s depiction of violence is beyond compare in their pure energy, staging, and veracity. When fists connect with faces or a foot connects with a groin, we feel it. Bodies quake when a bullet hits flesh; blood soaks, clothes are shredded, and the impact is undeniable, unlike so much anonymous Hollywood violence that seems to proceed without consequence. Verhoeven has often compared his childhood experiences growing up in The Hague under Nazi-occupied forces to a grand adventure (although others might describe it as a grand tragedy). Exposed to mass death, falling bombs, and untold horrors, the director has admitted to using this influence in his films, especially in gun battles and depictions of death. In his hands, such violence becomes replete with force. One sequence, in particular, features Quaid using a bystander as a human shield; the body is shredded by bullets to a staggering degree and, along with a body count of more than seventy tallied deaths, caused an anti-violence uproar upon the film’s release. It’s no wonder the ratings board initially saddled the picture with an X rating, much like Robocop, due to excessive violence, which had to be trimmed to receive an acceptable R.

While we ask ourselves questions about the head games being played on us, Verhoeven supplies a relentless pace and thrilling but oh-so-bloody violence amid the twists and turns. The director’s depiction of violence is beyond compare in their pure energy, staging, and veracity. When fists connect with faces or a foot connects with a groin, we feel it. Bodies quake when a bullet hits flesh; blood soaks, clothes are shredded, and the impact is undeniable, unlike so much anonymous Hollywood violence that seems to proceed without consequence. Verhoeven has often compared his childhood experiences growing up in The Hague under Nazi-occupied forces to a grand adventure (although others might describe it as a grand tragedy). Exposed to mass death, falling bombs, and untold horrors, the director has admitted to using this influence in his films, especially in gun battles and depictions of death. In his hands, such violence becomes replete with force. One sequence, in particular, features Quaid using a bystander as a human shield; the body is shredded by bullets to a staggering degree and, along with a body count of more than seventy tallied deaths, caused an anti-violence uproar upon the film’s release. It’s no wonder the ratings board initially saddled the picture with an X rating, much like Robocop, due to excessive violence, which had to be trimmed to receive an acceptable R.

With a lofty budget for its period of $60 million, Total Recall still looks like a wonder of marvelously conceived and realized sets and design work, almost all of it created using practical means as opposed to computer technology. The crew used massive miniatures to create exterior Mars shots, sparing no expense despite some studio backlash. The film was one of the last major productions to use extensive miniatures of this type; today, effects wizards leave it to computers to create such worlds. But the sole piece of early CGI here constitutes a memorable sequence in a walkthrough X-ray metal detector, through which Schwarzenegger jumps and destroys. Shooting in Mexico City, the crew made use of radical local architecture and bustling squares riddled with glowing advertisements to create a futuristic environment. Large platform walls and flat, gray structures evoke a minimalist, industrial future, whereas their use of the Insurgentes station, after repainting it entirely in terminal gray, creates a setting so perfect for the story that it could’ve been made on a Hollywood soundstage.

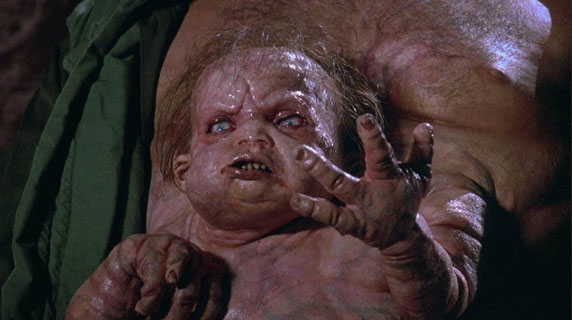

Most impressive are the special makeup effects rendered by Rob Bottin (The Thing) and the visual effects by Bottin and Eric Brevig (The Abyss). Bottin’s animatronic heads alone are genius. Take when Quaid has to remove a large tracking device from his skull through his nose, or when Quaid disguises himself as a fat lady using a robotic headpiece that malfunctions as he passes through Mars customs. Countless actors were made up for Mars’ mutant population, genetically warped by Cohaagen’s misapplied air mixtures. The granddaddy of them all remains Kuato, the leader of the mutant underground. Marshall Bell plays seemingly normal freedom fighter George, who opens his shirt to reveal his twin brother attached to his stomach—a freakish, slimy, psychic baby-thing controlled by some fifteen operators. Although released in 1990, the Kuato character remains so effective and memorable that Andy Samberg revived it for an odd SNL sketch in 2007, where Kuato and Scarlett Johansson’s female mutant counterparts aggressively lick each other. At any rate, almost every scene in Total Recall contains some kind of special effect, all of them unforgettable and made by top industry standards, resulting in the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences honoring the film with a “Special Achievement” Oscar in 1991 for its incredible visuals.

An immersive marketing campaign, Schwarzenegger’s popularity, and trailers depicting a special FX extravaganza helped generate more than $250 million in worldwide box-office receipts. In 1992, Goldman optioned Dick’s short story The Minority Report for a proposed sequel to Total Recall in which Quaid would become a cop who used Martian mutant precognitives to stop future crimes. Jon Cohen wrote the first draft of a screenplay that went unproduced for a decade. In the years subsequent to Total Recall’s release, Carolco went bankrupt due to expensive flops like Renny Harlin’s Cutthroat Island and Verhoeven’s Showgirls, and the project faded into Hollywood limbo. Cohen’s script eventually found its way to Tom Cruise, who revived the project by showing it to Steven Spielberg. After years of more delays and rewrites, the end result became Spielberg’s 2002 masterpiece Minority Report, which in no way relates to Verhoeven’s film, save for its author.

An immersive marketing campaign, Schwarzenegger’s popularity, and trailers depicting a special FX extravaganza helped generate more than $250 million in worldwide box-office receipts. In 1992, Goldman optioned Dick’s short story The Minority Report for a proposed sequel to Total Recall in which Quaid would become a cop who used Martian mutant precognitives to stop future crimes. Jon Cohen wrote the first draft of a screenplay that went unproduced for a decade. In the years subsequent to Total Recall’s release, Carolco went bankrupt due to expensive flops like Renny Harlin’s Cutthroat Island and Verhoeven’s Showgirls, and the project faded into Hollywood limbo. Cohen’s script eventually found its way to Tom Cruise, who revived the project by showing it to Steven Spielberg. After years of more delays and rewrites, the end result became Spielberg’s 2002 masterpiece Minority Report, which in no way relates to Verhoeven’s film, save for its author.

In spite of its impressive box office, no doubt a result of Schwarzenegger’s popularity at the time, the sensation of Total Recall is somehow strange. For an R-rated, bloody-as-hell science-fiction film to attract record crowds, it must be the 1990s. And though Schwarzenegger’s height of popularity then accounts for its success, today, his presence unfairly burdens the film with a stigma that has since formed about his usually brainless projects. Still, there’s something about the picture that endures regardless of being “just an Arnold Schwarzenegger movie,” an association for guilty pleasures laced with testosterone and gunpowder. That Verhoeven put together a sci-fi adventure, which to this day is such a watchable and thought-provoking picture, is a testament to its multi-dimensional appeal, beyond the basic action fodder which at first glance, Total Recall appears to be. This is one of my personal favorite films, a joyful contradiction to be embraced for its raw sensory energy and momentum, but savored for its unpredictably complicated Dickian themes exploring the nature of identity, fantasies, and reality.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review