Reader's Choice

Top Gun

By Brian Eggert |

The first images in Top Gun, the 1986 hit about Naval aviators that made Tom Cruise a superstar, build a montage that has the energy of a soft drink commercial. Against the opening credits, a ground crew aboard an aircraft carrier prepares planes for takeoff. It’s an iconic-looking sequence, complete with slow-motion and director Tony Scott’s regular use of red lens filters at sunrise to heighten the visual drama. Then Scott’s name appears onscreen, prompting jet engines to fire and Kenny Loggins to sing about the “Danger Zone.” Now the shots escalate to showcase planes taking off, marshallers directing traffic, aircraft landing, and the enthused reactions of the deck crew in a random confluence of guitar riffs and positivity. At any moment, you expect someone will open a Pepsi, look at the camera, and announce some hollow slogan. Legendary critic Pauline Kael, undoubtedly aware of Scott’s background in commercials, asked in her review of Top Gun, “What is this commercial selling?” She also noted the film’s famous homoerotic overtones, but that wasn’t intended by the filmmakers, even if it drips off the screen in salty beads of man sweat.

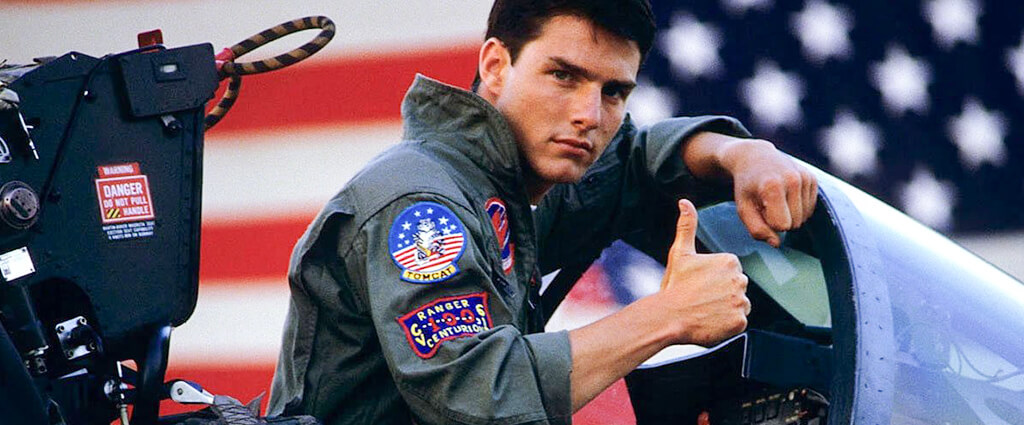

Instead, as intended, Top Gun serves as a jingoist chunk of Cold War propaganda designed to reinforce Reagan-era ideologies about being “the best”—a concept that saturated 1980s cinema in several Rocky sequels and various other sports and military movies. Even the poster’s tagline reads, “Up there with the best of the best.” But what does it mean to be “the best” in this context? If you’re the best, according to Top Gun, you’re an American. You rank the highest. You get the girl, but also your sexual conquests are many. You have zero body fat and look great playing shirtless volleyball. You respect your parents, particularly your father (and if he’s not around, the nearest father figure will do). You defeat the bad guys. You win the trophy. But if you come in second place, you can still be the best by learning a valuable lesson or making friends with the competition. After all of that, if you can walk away and give a thumbs up or high-five, then one way or another, you’ve become “the best.”

While watching Top Gun for the first time in over 20 years, I was struck by the film’s lack of conflict. I won’t bother to summarize its plot, as you no doubt know it, except to say the stakes feel undercooked. Faceless MiGs present an uncertain threat, appearing whenever screenwriters Jim Cash and Jack Epps Jr. need some action. Otherwise, the conflict centers around Maverick’s claim to being “the best” aviator in the US Navy. His cocksure behavior and ability to follow through make him the embodiment of “the best.” He flies recklessly but passionately, and that’s what Kelly McGillis’ civilian advisor Charlie finds so appealing. Yet, his self-satisfied and relentless smile when he follows Charlie into the ladies room, expecting her to put out right there, probably seemed charming in 1986 and the years to follow. Not so, today. In the end, even though the smarmy competition, Iceman (Val Kilmer), takes home the Top Gun trophy, Maverick proves good enough to teach future students. And he gets the girl. Although Maverick lost, it feels like he won.

While watching Top Gun for the first time in over 20 years, I was struck by the film’s lack of conflict. I won’t bother to summarize its plot, as you no doubt know it, except to say the stakes feel undercooked. Faceless MiGs present an uncertain threat, appearing whenever screenwriters Jim Cash and Jack Epps Jr. need some action. Otherwise, the conflict centers around Maverick’s claim to being “the best” aviator in the US Navy. His cocksure behavior and ability to follow through make him the embodiment of “the best.” He flies recklessly but passionately, and that’s what Kelly McGillis’ civilian advisor Charlie finds so appealing. Yet, his self-satisfied and relentless smile when he follows Charlie into the ladies room, expecting her to put out right there, probably seemed charming in 1986 and the years to follow. Not so, today. In the end, even though the smarmy competition, Iceman (Val Kilmer), takes home the Top Gun trophy, Maverick proves good enough to teach future students. And he gets the girl. Although Maverick lost, it feels like he won.

Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer produced Top Gun. Peter Biskin described them as “megaproducers” who “preferred novices they could hire for a song and push around, like Adrian Lyne or Tony Scott.” However, Bruckheimer got his start in the world of advertising, which might be why he’s drawn to commercial directors like Scott and Michael Bay. Scott, who started out making commercials for Ridley Scott Associates, was fresh off the heels of his feature debut and arguably his best film, The Hunger (1983), also produced by Simpson and Bruckheimer. And so, the talent behind the cameras on Top Gun was focused more on selling than on composing drama or telling a personal story. Indeed, the film exists for commercial synergy. It’s about creating individual moments that can be packaged and sold to audiences in a trailer. And it worked. The distributors at Paramount made millions in receipts and plenty more from soundtrack sales—the Oscar-winning song “Take My Breath Away,” performed by Berlin, joins Kenny Loggins and oldies by Jerry Lee Lewis (“Great Balls of Fire”) and The Righteous Brothers (“You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling”). It’s a memorable and best-selling soundtrack, and it’s also evidence of an increasing desire by Hollywood studios to sell just as many tapes and CDs as movie tickets.

While the film’s commercial enterprise resulted in a box-office triumph for Paramount, there were other consequences, some unintended. Author David Robb notes that the US Navy saw a 500% increase in enlistment from those wanting to become the next Maverick (or Cruise (or Kilmer)). The Navy cooperated with the production and helped back the film, suggesting its intended function as a recruitment tool. Top Gun also became inseparable from American pop culture, so fixed in the zeitgeist that its story serves almost no function next to the familiar images: Cruise’s smile, aviator shades (even at night), Cruise racing on a motorcycle next to a jet, unquestioning patriotism, “Great Balls of Fire” at the piano, plane fetishism, and sweaty interactions between sweaty men. Meanwhile, the queer association with Naval servicemen fuelled the film’s accidental but abundant homoerotic appeal, complete with lockerroom scenes and loaded dialogue (“You can be my wingman anytime” and “I’d like to bust your butt but I can’t”). And famously, Quentin Tarantino has a convincing monologue in the 1994 indie comedy Sleep with Me that argues how Maverick’s need to break the rules represents the emergence of his gay identity. However, queer readings easily apply to many examples from 1980s action cinema, which was rooted in male bonding, muscle obsession, and eroticized male bodies as ideal forms.

Some would argue that queerness is the text, but that’s a projection on another level. Top Gun proves so interpretable because the story is empty, inviting audiences to assign a greater meaning where none exists. This is why my primary hangup rests on the one-dimensional Maverick’s growth—because he doesn’t so much grow as fulfill his promise as the self-declared “best” pilot in the Navy. Predictably, he does justice to his late father’s legacy by earning the approval of Viper (Tom Skerrit), another father figure and the school’s commanding officer. Meanwhile, characters like Cougar (John Stockwell) and Goose (Anthony Edwards) represent clear sacrifices to bring importance and momentary humility to Maverick’s story through trauma. But those deaths hardly carry the weight they should, apart from a convincing performance by Meg Ryan as Goose’s widow. Maverick starts cocky, grinning from ear to ear because he knows he’s the best, and that’s just about where he ends up. In other words, there’s not much going on here in terms of character growth or overcoming conflict.

Some would argue that queerness is the text, but that’s a projection on another level. Top Gun proves so interpretable because the story is empty, inviting audiences to assign a greater meaning where none exists. This is why my primary hangup rests on the one-dimensional Maverick’s growth—because he doesn’t so much grow as fulfill his promise as the self-declared “best” pilot in the Navy. Predictably, he does justice to his late father’s legacy by earning the approval of Viper (Tom Skerrit), another father figure and the school’s commanding officer. Meanwhile, characters like Cougar (John Stockwell) and Goose (Anthony Edwards) represent clear sacrifices to bring importance and momentary humility to Maverick’s story through trauma. But those deaths hardly carry the weight they should, apart from a convincing performance by Meg Ryan as Goose’s widow. Maverick starts cocky, grinning from ear to ear because he knows he’s the best, and that’s just about where he ends up. In other words, there’s not much going on here in terms of character growth or overcoming conflict.

If the writers intended any kind of parallel for Top Gun, it’s between the Navy and a sports team. Maverick is the superstar who must learn to play in a team. Even the Top Gun locker room scenes feel similar to those seen in countless sports movies. Thus, the conflict against the opposing team—presumably the Soviets, though they remain unspecified—turns politics into a disturbing form of war-as-gameplay. The sports movie analogy proved so evident that even Hot Shots! (1991), the Top Gun spoof, lampooned this quality when Charlie Sheen’s hero returns from an aerial battle to a crowd of cheering servicemen. Replicating the familiar post-game question reporters often asked around this time, a voice from behind the camera inquires, “Now that you’ve killed the bad guy and made the world safe for democracy, what are you going to do to cash in on your newfound fame?” Sheen’s character replies like a Super Bowl victor: “I’m going to Disneyland!” To be sure, Maverick’s return home after their victory recalls many team celebrations (it’s surprising Gatorade isn’t dumped on Viper’s head).

And so, Top Gun doesn’t take my breath away. Whether it’s selling the idea of America’s military superiority and status as “the best” or simply rewarding Maverick’s overconfident behavior throughout, Top Gun feels more like a historical marker than an escapist blockbuster. Doubtless, you’re reading this review and telling me to “lighten up.” After all, Top Gun is a staple of Hollywood cinema, a landmark entry in Cruise’s career, and a gateway that led to Scott becoming a major action director (the impressive display of various high-speed dogfights are expertly filmed and edited). It’s all very cool looking, and its imagery is memorable in the way commercials from decades ago linger in the mind. But it didn’t make me feel anything. Perhaps if I had grown up watching Top Gun on repeated viewings, I would still love the film today and apologize for its missteps along with its devoted fans (the way I do for my personal favorites from this era). Alas, Top Gun remains a dramatically unsatisfying and mostly superficial experience, leaving my thoughts to wander, similar to how I zone out during the commercials before the main attraction. Whatever it’s selling, I’m not buying.

(Note: This review was originally suggested on and posted to Patreon on May 17, 2022.)

Bibliography:

Arnett, Robert. “Understanding Tony Scott: Authorship and Post-Classical Hollywood.” Film Criticism, vol. 39, no. 3, 2015, pp. 48–67, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24777935. Accessed 14 May 2022.

Biskind, Peter. Easy Riders, Raging Bulls. Simon and Schuster, 1998.

Modleski, Tania. “Misogynist Films: Teaching ‘Top Gun.’” Cinema Journal, vol. 47, no. 1, 2007, pp. 101–05, http://www.jstor.org/stable/30132003. Accessed 14 May 2022.

Robb, David. Operation Hollywood: How the Pentagon Shapes and Censors the Movies. Prometheus, 2004.

Schuckmann, Patrick. “Masculinity, the Male Spectator and the Homoerotic Gaze.” Amerikastudien / American Studies, vol. 43, no. 4, 1998, pp. 671–80, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41157425. Accessed 14 May 2022.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review