Tomorrowland

By Brian Eggert |

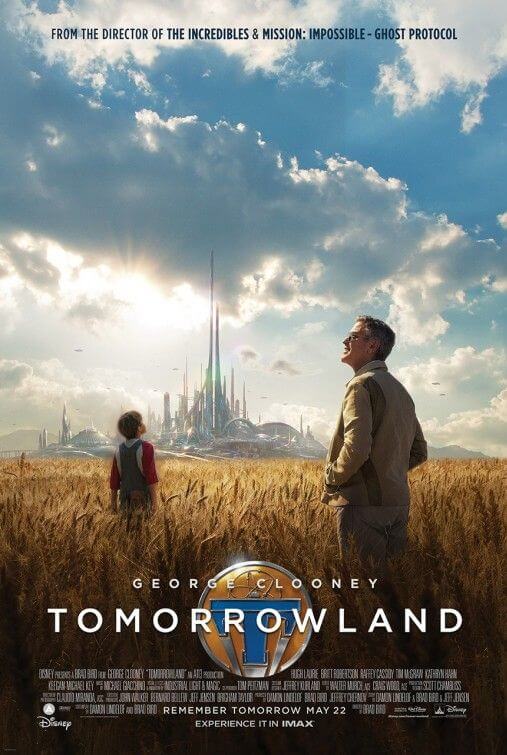

Brad Bird’s Tomorrowland is the kind of film that entertains in the theater but gradually degrades the more you think about it afterward. This rather preachy family adventure from Disney provides a level of high-concept science-fiction escape that would have made a dreamer like Walt Disney proud (and once inspired him to create the so-named quarter of Disney theme parks, or adapt Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea into a live-action feature in 1954). In fact, the film’s central message emphasizes the importance of dreamers who carry out their dreams, and here imagination reigns supreme in the form of robots, jetpacks, rocket ships, laser guns, and a utopian city of the future. Tomorrowland champions those visionaries who conceive the impossible, and then dare to make their visions a reality. However, the film fails to evoke the sense of wonder and awe it hopes to achieve through its onscreen spectacles, despite being fast-paced and diverting. In addition to some surprisingly underwhelming special FX, the film harbors glaring plot holes that leave the experience muddled, if not contradictory to its own purpose.

Maybe it’s unintentionally symbolic, then, that the film uses awkward bookends in which two narrators can’t decide how to tell their story. Eldest of the two is curmudgeonly scientist Frank Walker (George Clooney), who recalls when, as a young boy (played by Thomas Robinson), he attended the 1964 New York World’s Fair to demonstrate his first invention, a jetpack pieced together from spare parts and an Electrolux vacuum. A patronizing panel judge named Nix (Hugh Laurie) dismisses Frank’s malfunctioning contraption, but an inquisitive, British-accented young girl named Athena (Raffey Cassidy), seemingly Nix’s daughter, sees potential and sneaks young Frank a pin flashing only the letter “T”. After a trip on the “It’s a Small World” ride, the pin grants him access to an elevator that transports him to another dimension. Frank finds himself in Tomorrowland, a still-under-construction metropolis where advanced robots build glimmering, futuristic towers. That’s where young Frank’s story abruptly ends for now.

Cut to present-day Cape Canaveral, FL, where our second narrator, the plucky teen Casey Newton (Britt Robertson), lives with her father (Tim McGraw) and little brother (Pierce Gagnon). She’s a dreamer too and feels so upset over NASA dismantling a nearby launchpad that she sabotages their plans. Soon enough, Athena, still conspicuously young, delivers another mystifying “T” pin to Casey. But there’s no “It’s a Small World” ride this time; when Casey touches it, she’s instantly transported to Tomorrowland, where, in the distance, she sees the shimmering city, like Dorothy looking upon Oz. In a virtuoso sequence pieced together to look like an extended tracking shot, we follow Casey on a brief tour through the futuristic city, which looks more like one of the computer-generated fabrications from George Lucas’ Star Wars prequels than a living, breathing utopia. But Casey’s time there is limited, and in a desperate bid to get back, she searches for answers. From here, Tomorrowland becomes a road movie where Casey teams with Athena and the older, begrudging Frank, who has since been kicked out of Tomorrowland, to get back into the city of the future. Along the way, they encounter a series of nasty robots, ray guns, and other neat gizmos.

For PG-rated fare, the film is quite violent, with a number of human-like androids losing their heads courtesy of Athena, a spry fighter and, as it turns out, an android herself. Nevertheless, it’s a fun ride until the finale, when Tomorrowland proves the theory that every utopia ends up being a dystopia, depending on your perspective. Laurie’s character Nix rules Tomorrowland, which is now an inexplicably grim, filthy, and empty place inhabited only by Nix and some robots. He soapboxes about letting apathetic humanity destroy itself, and the resolution hardly fills one with wonder. Fortunately, Robertson gives an affable performance as a rambunctious lead, even if we’re constantly being told how smart and special her character is, though we never see it. Clooney is servable in a role without many gradations, playing the grump with a heart of gold. Stealing the show is Cassidy, whose performance is eerily composed, not at all like that of a child actor, and yet very charming.

Bird wrote the script with Damon Lindelof, from a story they conceived with Jeff Jensen, and they went to great lengths to keep the story a secret during production. Their screenplay could be described as being more about the journey than about the destination, which is usually what filmmakers say when they don’t have a satisfying conclusion. Lindelof has an appalling reputation for such promising science-fiction material that ends up being a disappointment. He contributed to Cowboys & Aliens (2011), Prometheus (2012), and served as showrunner for the television series Lost—all storylines that proved notoriously unsatisfying. In Tomorrowland, Bird and Lindelof get so wrapped up in the message that they forget to fill their plot holes by adequately exploring and describing their vision of the future. This comes as something of a shock for this critic, as Bird’s tightly scripted animated efforts (Ratatouille, The Iron Giant, The Incredibles) were perfectly balanced narratives, each celebrating creativity, post-WWII idealism, and nostalgia for simpler times. But rather than embrace and explore the optimistic future the way Disney did in the title’s theme park, they do the very thing their narrative preaches against and dwell on Nix’s view of humanity’s cynicism, gloom, and disenchantment.

But then, Nix has a point. And he delivers it in a particularly powerful, super-villainy speech. Human beings have a contemptible habit of thinking more about right now than about the distant future, more about instant gratification, even if it means selling ourselves short in the long run. Our postwar optimism for the future has been replaced by rampant pessimism. Indeed, most of us accept that our planet is slowly dying, overpopulated, and filled with violence and atrocity; however, any sweeping solutions are usually thwarted by politics, greed, and bureaucracy. We all know the problems exist, but because it doesn’t directly influence our daily lives at this very moment, we feel safe to ignore the warning signs and make it someone else’s problem. And then there’s our entertainment, which revels in predicting our demise by apocalypses of the nuclear or zombie brand (a videogame billboard for “ToxiCosmos 3” appears throughout the film). The point is, in both our lives and our various forms of amusement, we’re courting The End instead of trying to prevent it. Bird and Lindelof engage in a noble quest to snap their audience out of apathy. Stop thinking about the future as a dystopia, they seem to be saying, and use your imaginations to dream up something wonderful. Still, it’s ironic that they use an end-of-the-world scenario to deliver that message.

But then, Nix has a point. And he delivers it in a particularly powerful, super-villainy speech. Human beings have a contemptible habit of thinking more about right now than about the distant future, more about instant gratification, even if it means selling ourselves short in the long run. Our postwar optimism for the future has been replaced by rampant pessimism. Indeed, most of us accept that our planet is slowly dying, overpopulated, and filled with violence and atrocity; however, any sweeping solutions are usually thwarted by politics, greed, and bureaucracy. We all know the problems exist, but because it doesn’t directly influence our daily lives at this very moment, we feel safe to ignore the warning signs and make it someone else’s problem. And then there’s our entertainment, which revels in predicting our demise by apocalypses of the nuclear or zombie brand (a videogame billboard for “ToxiCosmos 3” appears throughout the film). The point is, in both our lives and our various forms of amusement, we’re courting The End instead of trying to prevent it. Bird and Lindelof engage in a noble quest to snap their audience out of apathy. Stop thinking about the future as a dystopia, they seem to be saying, and use your imaginations to dream up something wonderful. Still, it’s ironic that they use an end-of-the-world scenario to deliver that message.

Unfortunately, Bird and Lindelof don’t show us that an optimistic, utopian future can work; they only show us how the greatest minds in history failed to achieve a utopian society. Their concept of an ideal future is just that, a concept—a theoretical space that exists as a notion quickly sketched in CGI. Rather than giving their audience something truly visionary, a beacon of hope, an example to which one should aspire, they tell us to keep dreaming. In the face of such a failure, any hope of the film’s viewers walking away with some vital inspiration becomes the most unbelievable part of the entire experience—and here’s a film where the Eiffel Tower opens up to launch a rocket from a bunker beneath Paris. Whereas Tomorrowland could have been both a necessary censure of contemporary society and an inspirational call to action, it relegates to a bland “children are the future” message. It’s all very well-meaning, but the plot remains contrived because the filmmakers are more interested in delivering a message than a smartly crafted adventure. At worst, Tomorrowland boasts some contradictions and resorts to propaganda; at best, Bird blends a fun visual ride into an ideologically skewed story. The result is an admirable failure.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review