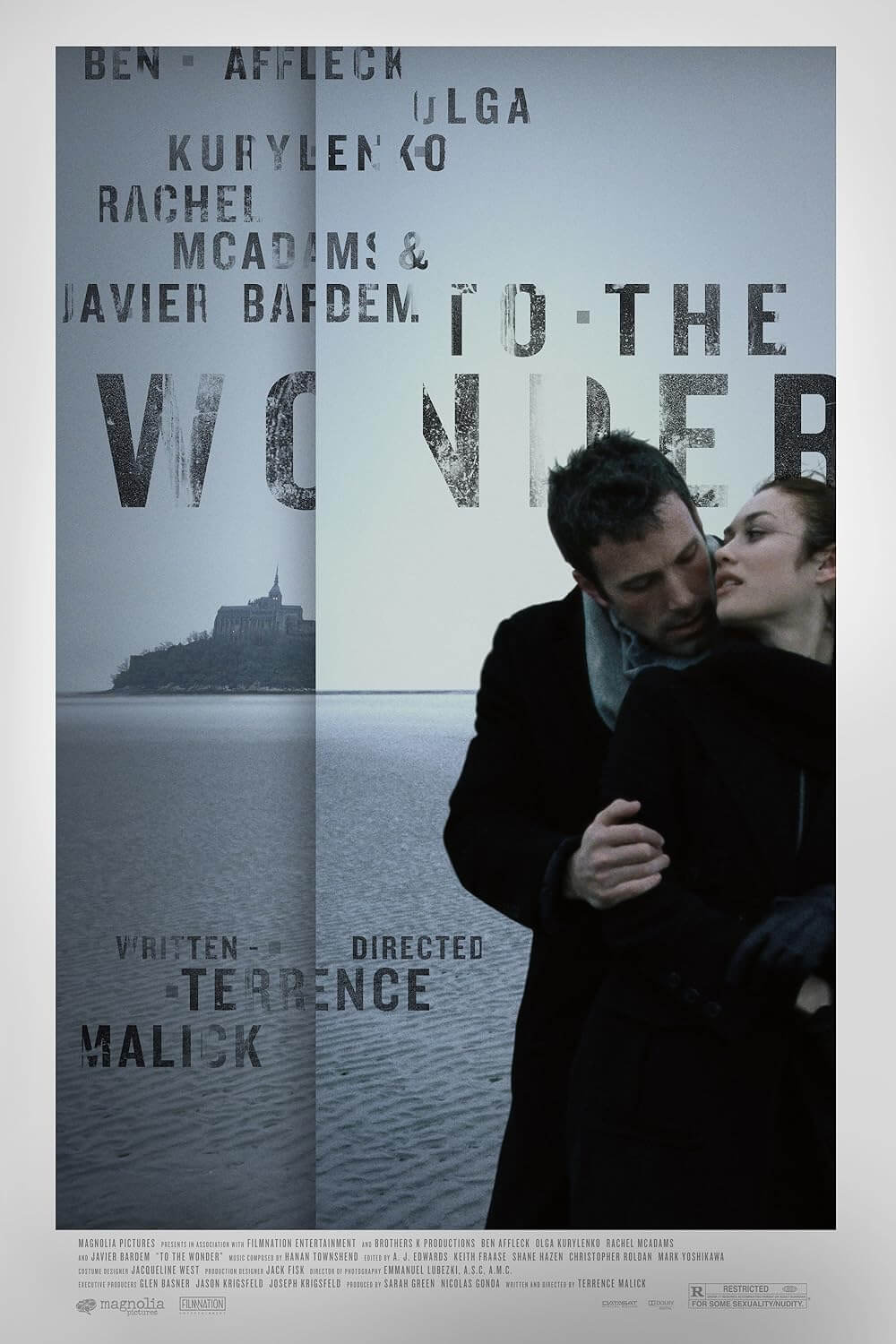

To the Wonder

By Brian Eggert |

An almost avant-garde rumination on love and Nature, Terrence Malick’s deeply powerful To the Wonder is an experiment in impressionist filmmaking. The reclusive writer-director of The Tree of Life has never made a film quite like this, although his pictures are often graceful searches for truth amid grander designs such as war, faith, love, destruction, and even the origins of the universe. After 40 years of making films, this is only the director’s sixth effort, and his resistance to narrative in To the Wonder feels like the work of a much younger filmmaker—far more investigational than the most recent effort of a long-acclaimed master. The film, which debuted at the Venice Film Festival to a combination of jeers and applause, uses stunning visuals that evoke what the skeletal story refuses to clarify. Images flow on and offscreen and flow into each other, while Malick’s unique use of poetic voiceover, usually a trait that brings his themes together, feels more like another note in a soft-playing symphony. Audiences unwilling to feel their way through the film will undoubtedly respond with boredom or confusion, whereas even those versed in Malick’s approach may find the experience a challenge to penetrate.

What story there is revolves around an American man, Neil (Ben Affleck), and his romances with the Parisian Marina (Olga Kurylenko) and his former schoolmate Jane (Rachel McAdams) from back home. He meets Marina in Paris, and their playful affair leads them to the Normandy island of Mont Saint-Michel. They walk to the top of this “Wonder of the West,” and the viewer gets the sense early on that the entire film will be about a journey toward love, and the awe of love as it relates to Nature. It becomes more than a brief affair when Neil asks Marina to return to his home in Oklahoma and bring her daughter, Tatiana (Tatiana Chahine), whose father has abandoned them. Once in America, the flame begins to fade as Neil is a solitary and quiet man; Affleck’s performance is almost completely devoid of dialogue. Eventually discontented, Marina and her daughter, who has trouble adjusting to American life, leave to return to Paris. Neil then finds Jane, but their association is short as Marina soon returns and marries Neil to get her green card.

Affleck’s character seems removed from his emotions, just as Marina seems unsettled in her turbulent marriage. A bohemian spirit, Marina dances about in most scenes, frolicking and playing at freedom though she’s pinned down by love. Neil, whose environmentalist work isolates him in a community riddled with the toxins of nearby oil drilling runoff, carries a weight around with him. So too does another key character, the town’s Catholic priest, Father Quintana (Javier Bardem). His parishioners say they’ll pray for him because he appears outwardly lonely and saddened, but finding God is no easier than Neil feeling comfortable in his crumbling environment or Marina resolving to settle down. The forward motion of these characters stops, and they weigh their choices and reflect on the natural world around them, the beautiful fields and farms, the neighborhoods filled with residents physically scarred by the rape of their soil and water supply.

These details on their own bear little impact on how the film affects us, curiously enough. We’re more consumed with the beauty of this abstract motion picture than any developments we might pull from what’s onscreen. Emmanuel Lubezki’s Steadicam hovers through scenes, gliding back and forth like drapes in the wind, passing and infiltrating characters who often seem to be doing nothing at all beyond sharing space. But any image from the film is beautiful enough to frame and hang on a wall. Lubezki catches sunsets beyond vast fields and an odd balloon effect held by the sand at the Normandy beach. We’re consumed by Nature’s beauty, as is often the purpose of a Terrence Malick film. There’s also a certain pensive, contemplative quality about watching actors who worked without any script and occupy their spaces by interacting with one another in intuitive ways. They’re not so much performances as observations of behavior. It’s mesmerizing in a way only hinted at in Malick’s earlier films, yet seems a natural progression from Badlands (1973) onward.

These details on their own bear little impact on how the film affects us, curiously enough. We’re more consumed with the beauty of this abstract motion picture than any developments we might pull from what’s onscreen. Emmanuel Lubezki’s Steadicam hovers through scenes, gliding back and forth like drapes in the wind, passing and infiltrating characters who often seem to be doing nothing at all beyond sharing space. But any image from the film is beautiful enough to frame and hang on a wall. Lubezki catches sunsets beyond vast fields and an odd balloon effect held by the sand at the Normandy beach. We’re consumed by Nature’s beauty, as is often the purpose of a Terrence Malick film. There’s also a certain pensive, contemplative quality about watching actors who worked without any script and occupy their spaces by interacting with one another in intuitive ways. They’re not so much performances as observations of behavior. It’s mesmerizing in a way only hinted at in Malick’s earlier films, yet seems a natural progression from Badlands (1973) onward.

Malick’s system of filmmaking involves shooting considerable amounts of footage and sculpting it down into sometimes multiple cuts, most of which have never been seen by the public, if they exist at all (as mentioned, Malick is very secretive about his process). For The Thin Red Line (1998), the director shot over a million feet of footage and then completed multiple versions, including a narrative version and a wholly impressionistic version; the theatrical cut was a combination of the two. For To the Wonder, Malick shot in 2009 and employed several editors to assemble the theatrical cut, simplifying the story and themes by altogether removing several actors from the screen (among them Jessica Chastain, Amanda Peet, Barry Pepper, Michael Sheen, and Rachel Weisz), as he’s been known to do. The resulting elegy feels nothing like a star-power romance and more like a painterly art piece. If Malick once again made several cuts of his film, he chose to release the impressionist version through distributor Magnolia Pictures, an independent label that makes up for risky projects by releasing them to VOD vendors the same day as their theatrical debut.

Do not waste time thinking about what might be included in a possibly nonexistent narrative cut. What an audience makes of To the Wonder must be a personal experience, although the basic threads of the story have autobiographical relevance for the director. Somewhat like Neil in the film, Malick married a French woman and, after getting a divorce, later married an old sweetheart; but these details are insignificant when it comes to identifying both the themes of marvel, love, and Nature present throughout the picture and what those themes mean to you, the viewer, if anything. Of course, mainstream or commercial audiences who already know they’re bound to find Malick’s impressionist style too experimental or radical should stay away. Even though at 112 minutes To the Wonder is Malick’s shortest film since his first, it will feel endless to moviegoers not open to the experience of film as visual and aural poetry. Unlike his previous narratives marked by his searching voiceover and prevailing spirituality, To the Wonder is wholly unique and even daring within his body of work. This is a gorgeously photographed, delicately scored (to Haydn, Tchaikovsky, and Wagner among Malick’s other oft-used composers), extraordinarily moving picture whose admirers will be few, yet finds an ardent enthusiast in this critic.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review