Reader's Choice

Titanic

By Brian Eggert |

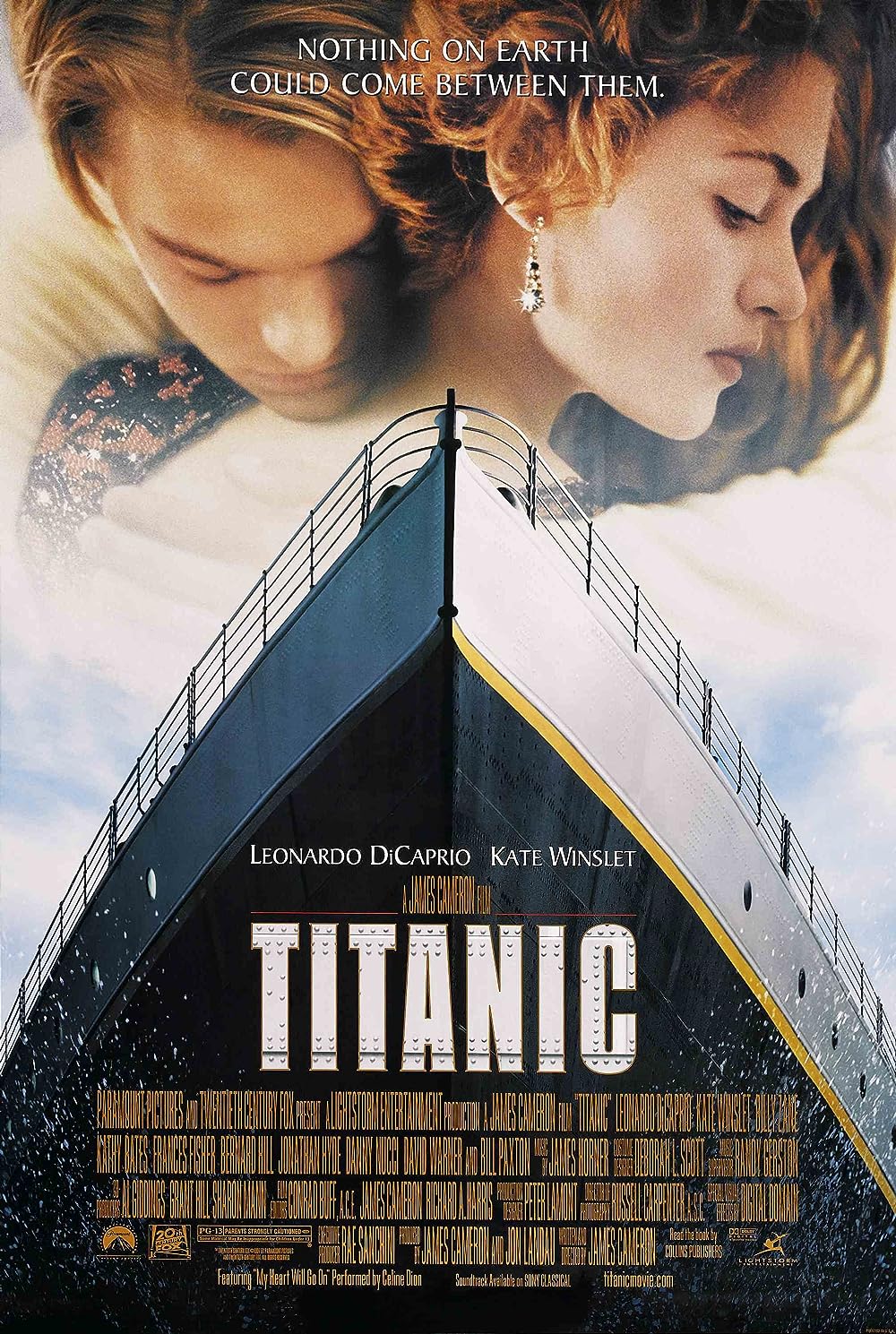

After unbridled celebration, followed by backlash that threatened to delegitimize its legacy, and then ongoing debate about its worth, James Cameron’s Titanic, a tale of romance and shipwreck, remains a generous, compassionate spectacle. Today, it’s difficult to grasp the phenomenon and its omnipresence in pop-culture. After becoming the highest-grossing film of all time, it turned into a cultural landmark and reference point to be quoted, lampooned, revered, and copied. Stars Kate Winslet and Leonardo DiCaprio became the faces of our romantic yearning, while “Kate and Leo” became shorthand for a coupling, almost as universal as saying “Romeo and Juliet,” despite their romance being limited to their respective characters, Rose and Jack. And then there’s Celine Deon, whose career still relies on the Oscar-winning song, “My Heart Will Go On.” Most of the discussion about the film occurred in the years immediately following its release in 1997, leading up to Cameron’s next biggest-movie-of-all-time, Avatar, from 2009. Upon revisiting the film for the first time in about twenty years, I was struck by its humanness. Stepping back from the cultural sensation of the thing, Cameron’s devotion to craft, detail, and accessible storytelling remains at the center of this viewing experience. And though the special FX and visual splendor were once central to the famously expensive production, those elements, which have aged to varying degrees of satisfaction, remain secondary to its touching melodrama.

Rare is the Cameron film that fails to engage both the heart and the senses. From The Terminator and its sequel to Alien, from The Abyss to True Lies, his work is rooted in humanity, though each of these films is propelled by high-concept action. Even Avatar, a film often praised for its eye-popping CGI over its complex characters, requires our empathy for a marginalized and subjugated alien race—characters realized with computers, though they prove more sympathetic, thus more real, than the story’s human colonizers. Titanic follows Cameron’s usual track on the heart and senses, immersing the viewer in a passionate love affair, while also dropping us into a desperate situation of survival and panic. It works so well because it places the viewer into impossible circumstances. We know what will happen: the ship will sink in the North Atlantic after striking an iceberg, leaving 1,500 of its passengers dead. But during its nearly three-and-a-half-hour runtime, Cameron manages to make the viewer forget about the disaster and lose ourselves in a tale of class elitism and impassioned romance—the stuff of a classic melodrama.

For well over an hour, the viewer is effortlessly drawn into a story of star-crossed lovers on a “ship of dreams,” to the extent that, when the iceberg finally makes an appearance, Cameron has succeeded in making us forget that the ship will inevitably sink. No longer are we passive viewers, watching the famed disaster from a safe historical distance, like passers-by watching a car wreck with perverse curiosity. He has turned us into participants who dread the sinking ship and ache for its passengers. We experience it. “I never got it,” says deep-sea researcher Brock Lovett (Bill Paxton) who’s obsessed with the treasures lost on the sunken RMS Titanic. “I never let it in.” Not until Lovett hears Rose’s stirring, personal account of the events leading up to the ship’s demise does he fully understand the power and humanity of the Titanic’s story. The film makes us realize that, if we’ve read non-fiction accounts of the Titanic disaster (or even just the Wikipedia entry), their descriptions of the ship and dry historical summations have failed to capture our emotions and imagination the way cinema can. Lovett, a modern-day pirate with an earring, is evidently the audience’s proxy. He has approached the sunken ship from the perspective of its aftermath, an amazing story whose only basis in reality are the artifacts disintegrating at the bottom of the ocean.

Cameron’s ability to reframe our perspective speaks to his skill as a storyteller, though he often receives more credit as a technical director. What attracted me on this viewing of Titanic was how well the flashback story structure frames the disaster through the lens of a melodrama; it both prepares us for what’s coming and uses our foreknowledge to enhance our engagement. The film opens with Lovett using underwater drones and searching for the “Heart of the Sea,” a fictional diamond that represents the ultimate payday. Instead, he finds only a drawing of Rose, sketched on the day the ship sank. Gloria Stuart plays the 100-year-old survivor, who soon arrives on Lovett’s vessel to tell her story, what is promised to be a grand tale of love and feminist awakening that also explains what happened to the diamond. Lovett listens, and so do we. By making us Rose’s audience, Cameron has thus piqued our curiosity from the perspective of a treasure-hunter, historian, participant in the wreck, and audience member in cinema (or home theater).

Before the old woman tells her story, one of Lovett’s experts plays a crude animated recreation of what scientific evidence suggests happened to the ship, explaining why it sank in layman’s terms. This is a stroke of genius on Cameron’s part. It establishes just what will happen to the ship later in the film, but it does so with unconvincing animation that appears laughable next to the spectacle Cameron has in store. But first, there’s an enchanted love story. Leonardo DiCaprio’s Jack, a starving artist and “tumbleweed blowin’ in the wind,” wins his passage to New York aboard the newly christened ship, where he finds Kate Winslet’s Rose in a doomed engagement to the über-rich and patriarchal Cal Hockley (Billy Zane). It will be a marriage of convenience, urged by Rose’s conscientious mother Ruth (Frances Fisher), regardless of whether the idea of marrying Cal makes Rose want to commit suicide. Jack prevents Rose from leaping into the icy waters of the Atlantic and earns himself a seat at a stuffy dinner with Rose’s circle of first-class bluebloods, which Cameron contrasts with the party below decks in the third class compartments—a scene of Irish dancing and drinking in which Rose and Jack fall madly in love. After Rose devotes herself to Jack, poses for a nude drawing, and makes love with him in the cargo hold, the ship hits the dreaded iceberg due to a number of oversights and unnecessary risks by Captain Edward John Smith (Bernard Hill) and crew.

The breakthrough CGI of the ship and its eventual plunge into the ocean looked uneven in 1997 and still wobbles today. The initial shots of the RMS Titanic at port, where Cameron’s indulgent digital frame passes over loading docks flooded with passengers, are among the film’s best. Later, when Kate and Leo have captured the audience’s gaze, it’s best not to look at the ship nor dwell on certain lines of dialogue (“I’m flying, Jack!”). Once it strikes the iceberg, about 90 minutes into the picture, the remaining runtime shows Cameron at his best: he delivers a relentless procession of increasingly desperate circumstances that seem to build and build with almost unbearable tension. Doorways burst open from water amassing on the other side, hallways become claustrophobic spaces of ice-cold current, the first-class snobs try to prevent the third-class passengers from making it to the lifeboats. Each of Cameron’s action films unravel in this way, rushing from one breathless moment to the next. Titanic is no exception. As Cameron puts us in the middle of these situations, we remember the computer simulation shown by Lovett’s colleague earlier in the film, except now the progression of events that lead to the ship sinking look real. Well, mostly. The smokestack that falls into the water onto Jack’s friend Fabrizio, played in a gross Italian stereotype by Danny Nucci, has always looked fuzzy and pixelated. But images of the half-submerged ship, its lights glimmering on the still surface of the Atlantic, remain visually arresting.

Less convincing is Zane’s performance as Rose’s husband-to-be, the resident villain. Underneath a laughable wig and over-groomed eyebrows, Zane overacts every gesture and every expression to intolerable degrees. His presence approaches camp and almost single-handedly derails the film’s integrity. Perhaps this was Cameron’s intention—to create such a deplorable, visually artificial man that could only serve to bolster another of his strong heroines. Indeed, though Leo received top billing and adorned the many posters that covered the bedroom walls of teenage girls in the 1990s, the film belongs to Winslet’s Rose DeWitt Bukater. The film’s main narrative thrust, after all, follows Rose from an oppressed turn-of-the-century woman to an independent, modern feminist determined to be a survivor. In Jack’s last moments, as he progresses into deeper shades of blue as he freezes, Rose promises him that she will “survive”—it’s the only thing that will give his death meaning. This self-actualization arc reaches beyond her romance with Jack and outlasts the titular passenger liner; it is an arc that follows Rose from the docks, where’s she’s little more than Cal’s garnish, to some eight decades later when she’s 100 years old, having lived a full life. In that sense, the common criticisms of Cameron’s film, which question the utility of a love story in the middle of a disaster film, are misguided and overlook the dramatic focus on Rose, not Jack and Rose.

Every James Cameron film boasts a strong woman that defies the reductive stereotypes of her gender: Sarah Connor (Linda Hamilton) in The Terminator and T2: Judgment Day, Ellen Ripley (Sigourney Weaver) in Aliens, Dr. Lindsey Brigman (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio) in The Abyss, Helen Tasker (Jamie Lee Curtis) in True Lies, and Neytiri (Zoe Saldana) in Avatar. Rose belongs among them, whereas Jack is secondary—a catalyst that helps Rose gain a sense of independence, fight for a life away from Cal and her mother, and escape from the reductive roles of motherhood and familial obligation. Of course, Jack saves her life on a number of occasions as the boat begins to flood, and he helps maintain hope in those final moments in the water. And much of the film is seen from his point of view, such as when he waits for Rose on the stairs—a scene that quickly shifts to Rose’s point of view. She watches Jack waiting before she descends the stairs, and the moment culminates in a dreamily romantic embrace (right under the nose of Cal and Rose’s mother no less).

Rose is the one who, after Cal’s bodyguard (an excellent David Warner) captures Jack and handcuffs him to a pipe, ventures into the flooding corridor to find an axe, which she then carries back, guiding herself along in four-foot-deep water with one hand clinging to the overhead pipe and another gripping the axe, and uses it to break her man free. She’s the one who liberates herself from the gold-digging ambitions of her mother (“Oh, Mother, shut up!”) because she would rather die than be reduced to a mere obedient wife on her rich husband’s arm. And she’s the one who takes the entire wooden door for herself, inciting endless debates about whether Jack could have fit (The Answer: he could have fit; they should have piled atop one another to keep warm). She’s also the one who doesn’t want her memories turned into a museum piece to be fawned over and profited from by men such as Lovett, leading her plop the “Heart of the Sea” into the dark waters of the Atlantic, if for nothing else than her own peace of mind. My point is this: Titanic may be a disaster film with a secondary melodrama attached to it, but the auxiliary narrative is not just a love story. It’s a tale of a woman shifting from an object to a subject.

Before Titanic’s debut, it was impossible to escape the discussion about it. Whether or not you followed movies, you knew about the scope and subject of Cameron’s film. It may be the last of its kind in that sense, a true crossover film. Media outlets everywhere covered its long and historically expensive production. I was fourteen when I first read the behind-the-scenes reports. It was the first film whose development I followed in magazines like Entertainment Weekly and Premiere, and also on the relatively new concept of online film forums, where commentators remarked that the incredible $200 million budget required two major studios (Twentieth Century Fox and Paramount Pictures) to finance it, not to mention Cameron’s own salary, which he contributed to offset the production costs. And what if the film bombed? Would Cameron, director of Aliens and The Abyss, two of my favorite films as a teenager, suddenly lose everything? The delay from July to December 1997 certainly indicated a troubled production. Elsewhere, reports of Cameron’s behavior compared him to Captain Bligh: he screamed at technicians about getting things right; some even raised concerns about the actors’ safety. But then Cameron is not only a perfectionist but a bona fide genius. Much like Stanley Kubrick, he labors over every detail, and he knows the craft so well that, if you’re working on his set, he can probably do your job better than you can. He is a demanding visionary who once compared filmmaking to a war between art and commerce, and he has perpetuated that war with his behavior.

Before Titanic’s debut, it was impossible to escape the discussion about it. Whether or not you followed movies, you knew about the scope and subject of Cameron’s film. It may be the last of its kind in that sense, a true crossover film. Media outlets everywhere covered its long and historically expensive production. I was fourteen when I first read the behind-the-scenes reports. It was the first film whose development I followed in magazines like Entertainment Weekly and Premiere, and also on the relatively new concept of online film forums, where commentators remarked that the incredible $200 million budget required two major studios (Twentieth Century Fox and Paramount Pictures) to finance it, not to mention Cameron’s own salary, which he contributed to offset the production costs. And what if the film bombed? Would Cameron, director of Aliens and The Abyss, two of my favorite films as a teenager, suddenly lose everything? The delay from July to December 1997 certainly indicated a troubled production. Elsewhere, reports of Cameron’s behavior compared him to Captain Bligh: he screamed at technicians about getting things right; some even raised concerns about the actors’ safety. But then Cameron is not only a perfectionist but a bona fide genius. Much like Stanley Kubrick, he labors over every detail, and he knows the craft so well that, if you’re working on his set, he can probably do your job better than you can. He is a demanding visionary who once compared filmmaking to a war between art and commerce, and he has perpetuated that war with his behavior.

Of course, time flattened many of the pre-release concerns about Titanic. Today, it’s almost commonplace for studios like Disney and Warner Bros. to spend $200 million (often much more) on the latest superhero extravaganza, and media outlets regularly cover the productions of such megabudget titles. What remains unique about Titanic is how ubiquitous it was in the zeitgeist. It still holds a record for remaining number one at the box-office for fifteen consecutive weeks, whereas subsequent earners such as Cameron’s Avatar, Star Wars: Episode VII – The Force Awakens (2015), and Avengers: Endgame (2019) each had comparatively shorter runs in first place at the multiplexes. Everyone saw Titanic, regardless of their demographic. Adjusted for inflation at the time of this review, Titanic’s ticket sales have only been out-performed by four films in the history of cinema: Gone with the Wind (1939), Star Wars (1977), The Sound of Music (1965), and E.T.: The Extra Terrestrial (1982). No film in the twenty-first century even comes close, and it’s difficult to imagine another film like Titanic coming along to unite our fragmented society, which depends so much on specificity and cultural bubbles that a crossover film such as this seems impossible.

At the Academy Awards ceremony on March 23, 1998, Titanic still held a top spot at the box-office several months after its initial release. Its staying power—flourishing on a curious mixture of spectacle, history, romantic melodrama, thrills, and teenage girls crushing on Leonardo DiCaprio after his breakout success on Romeo + Juliet (1996)—was unprecedented. Cameron’s film, which naysayers predicted would flop, earned a whopping eleven Oscars, setting a record only matched by Ben-Hur (1959) and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003). Cameron recognized the situation in his acceptance speech for Best Director: “I’m king of the world!” he proclaimed like a true cornball, while he also drove home the point that his detractors were so embarrassingly wrong about his monumental project. If Cameron’s ego about his craft and success became part of his (sometimes maligned) persona in Hollywood, the situation was escalated by the performance of his next feature, Avatar, which was the first film to unseat Titanic’s record-breaking performance. Both Titanic and Avatar sold more tickets than the MCU’s current record-breaker, Avengers: Endgame. And so perhaps Cameron’s ego remains justified, despite what could be described as a lack of modesty on his part.

Ultimately, this discussion of box-office performance and cultural significance serves to contextualize Titanic’s place and importance in history, though the film’s cultural footprint extends beyond its monetary totals or the number of awards it received. It’s an impressive object for what it represents, as Roger Ebert observed: “Movies like this are not merely difficult to make at all, but almost impossible to make well.” To be sure, the number of things that had to go right for Titanic to work as it does are staggering to imagine. But these discussions are extratextual of the film itself. Push aside the phenomenon, which too often limits Titanic’s place in film history, and what’s left is an immersive and affecting experience that may have been lost amid the talk about its making, its superstar performers, and its box-office receipts. In the end, I didn’t care about the countless awards or the monumentality of the production; I found myself engaging with Rose and her journey of Self, and less immersed in the sheer spectacle of it all.

(Note: This review was suggested by supporters on Patreon.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review