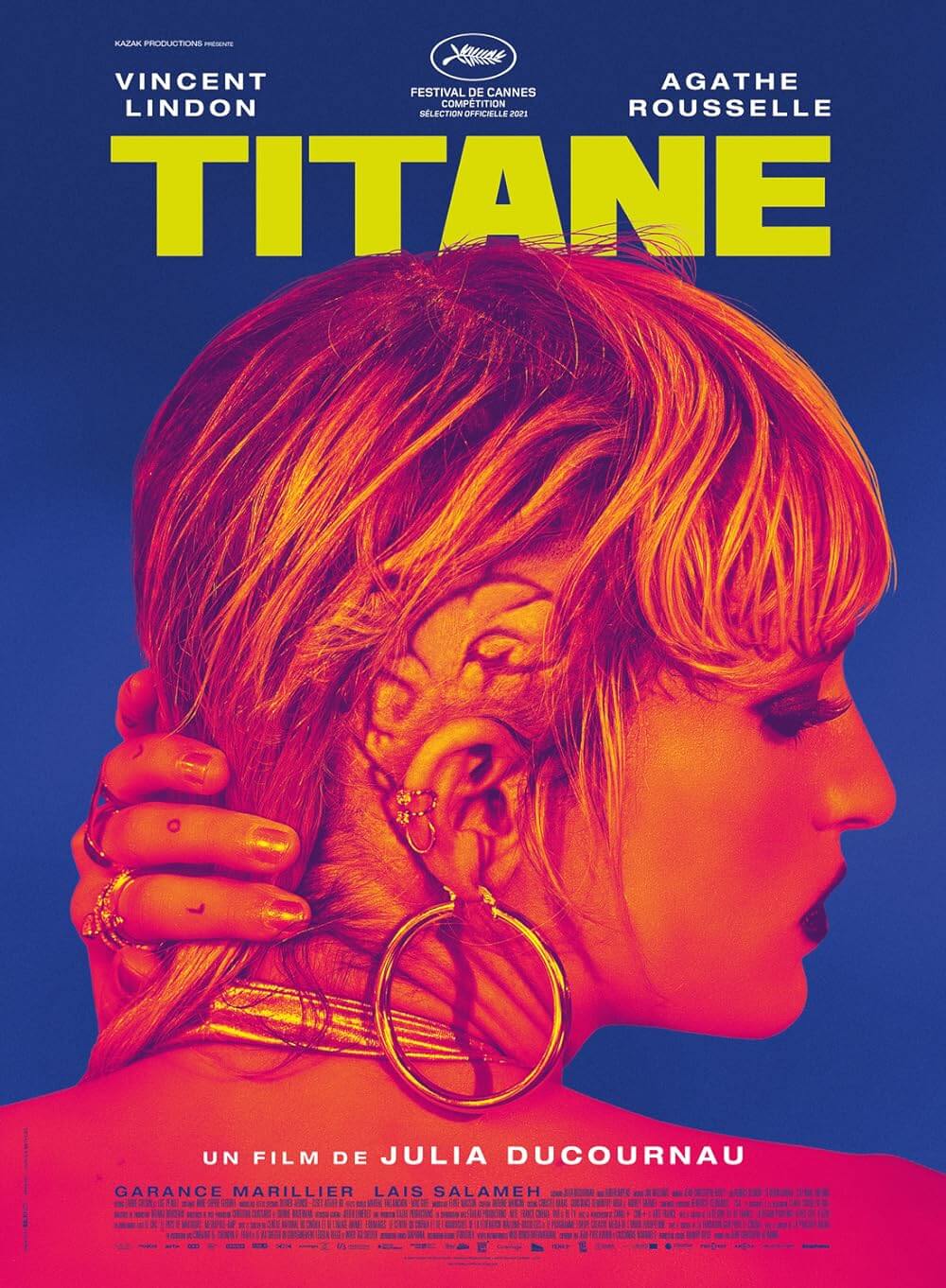

Titane

By Brian Eggert |

In the first images of Titane, the camera lingers on engine parts shot like sweaty appendages, dripping with perspiration and vibrating orgasmically with the motor’s hum. The metal shimmers with grease and droplets of oil, and its curves look almost fleshy in the way they bend and give way to the rolling shapes in the undercarriage. French director Julia Ducournau films these inhuman auto parts like erotica, exploring the connection between bodies and automobiles in ways not attempted since David Cronenberg’s controversial 1996 film, Crash, about the relationship between the little death and the death drive. The link between sexuality and cars has been there for a long while. After all, why do they call a mechanic’s workspace a body shop? Consciously or not, motorheads make these connections as well. Car magazines and calendars pair bikini-clad women with muscle cars and hot rods, coupling sex and automobiles in literal and figurative terms. Ducournau’s film considers how the male gaze creates this strange relationship of images and takes the next logical step. The result is something wildly original, brutally visceral, oddly funny and tender, and singular in its vision.

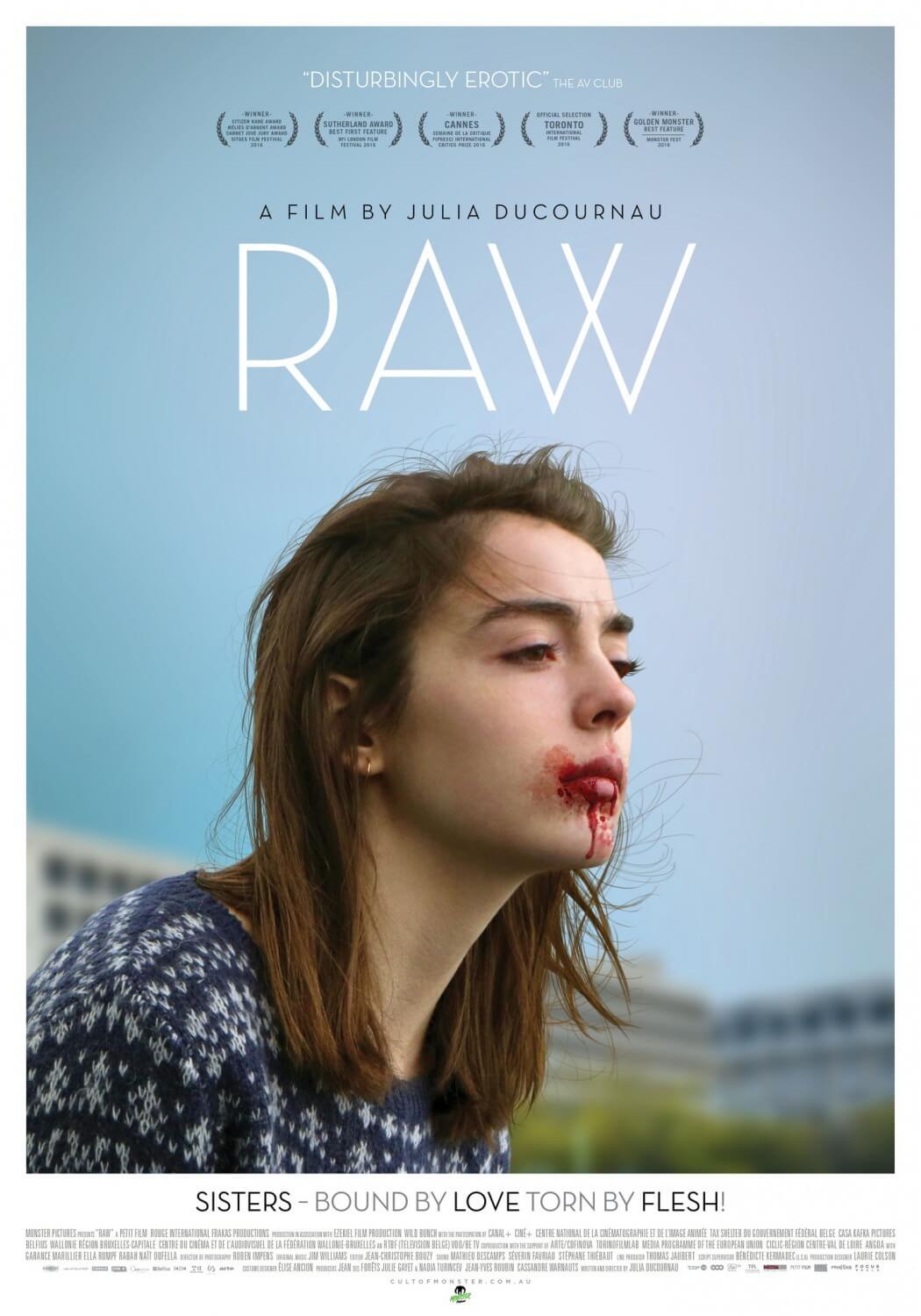

Winner of the Palme d’Or at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, Ducournau’s film is literate and carnal, cerebral and barbaric, and unsettling yet with a depth of feeling. Her film supplies a borderline facetious body horror prompt to confront the gaze. When her protagonist, Alexia (newcomer Agathe Rousselle), ultimately has sex with a car that impregnates her, Ducournau seems to ask men compelled by such images, “Is this what you want, a woman and a car?” The French word for titanium, Titane (pronounced tee-tahn) sounds like the name of a mythic heroine whose superpower involves metal, which might be the ultimate male fantasy for those who consider their pickup truck an extension of their phallus. Ducournau turns that idea on its head, yet she explores the imagery in layered terms. However, Titane’s reputation as a film “about a woman fucking a car” captures only the surface. Similar to her debut feature Raw (2016), a film that used cannibalism as a metaphor for emerging desires in young adulthood, Ducournau’s interest lies beyond the immediate conceit—that’s just a launchpad to investigate how the body’s fetid processes, needs, desires, and malformations give the individual shape.

Alexia’s eventual sex with a Cadillac occurs after an automobile reshapes her body as a child. Early on, we meet the preadolescent Alexia (Adèle Guigue). She loudly hums the sound of an engine in the back seat of the family car, much to her father’s (director Bertrand Bonello) annoyance. He turns the volume up on the radio to ignore her. But she just hums louder and begins to kick the back of her father’s seat. After he yells at her, she takes off her seatbelt, and he turns to stop her, screaming for her to put it back on. All at once, he loses control of the car, and they spin into a Jersey wall. Alexia needs a titanium plate to replace sections of her fragmented skull, leaving a nasty scar of folded skin above her right ear. Reading the girl’s harsh look in the hospital and her father’s equally empty, cruel expression, the two do not share a strong bond. There’s no embrace after her recovery and no apology. Maybe it’s because she’s technically a cyborg now, or perhaps she has always loved automobiles. But when the hospital releases Alexia, she hugs and kisses the family car, glad the damage was only slight. When Titane transitions to Alexia as an adult, her relationship with her father has not improved. She still lives at home with her parents, and he seems to look at his daughter with contempt, as though he knows her many secrets.

Alexia’s eventual sex with a Cadillac occurs after an automobile reshapes her body as a child. Early on, we meet the preadolescent Alexia (Adèle Guigue). She loudly hums the sound of an engine in the back seat of the family car, much to her father’s (director Bertrand Bonello) annoyance. He turns the volume up on the radio to ignore her. But she just hums louder and begins to kick the back of her father’s seat. After he yells at her, she takes off her seatbelt, and he turns to stop her, screaming for her to put it back on. All at once, he loses control of the car, and they spin into a Jersey wall. Alexia needs a titanium plate to replace sections of her fragmented skull, leaving a nasty scar of folded skin above her right ear. Reading the girl’s harsh look in the hospital and her father’s equally empty, cruel expression, the two do not share a strong bond. There’s no embrace after her recovery and no apology. Maybe it’s because she’s technically a cyborg now, or perhaps she has always loved automobiles. But when the hospital releases Alexia, she hugs and kisses the family car, glad the damage was only slight. When Titane transitions to Alexia as an adult, her relationship with her father has not improved. She still lives at home with her parents, and he seems to look at his daughter with contempt, as though he knows her many secrets.

There’s a lot to hide. Alexia works at auto shows that feature souped-up vehicles accompanied by scantily clad women who perform erotic dances with the cars. It’s a scene straight out of The Fast and the Furious in its fetishization of women’s bodies and automobiles. Alexia is something of a celebrity in this circuit. Bodyguards have to keep aggressive fans away, ordering, “Hands off, sir. Touch with your eyes.” Atop the hood of a vintage Cadillac painted with orange and purple flames, she dances, and her performance pantomimes having sex with the car. After the show, an obsessed fan chases Alexia to her car. He asks for an autograph, then a kiss. Alexia gives it to him, and then she gives him her metal hairpin in his ear. It’s not the first time she has killed, either. And it won’t be the last. But just when you think Ducournau has concocted a French slasher that might be called The Hairpin Killer, something curious happens that takes Titane into another world altogether.

The film becomes a disturbing fantasy when Alexia returns to the auto show locker room to shower her victims’ foaming sputum out of her hair. While cleaning herself, she hears an engine revving in the garage. Stark naked and still wet from her shower, Alexia searches out the sound and finds the flamed Cadillac waiting, its lights on. She climbs inside and positions herself atop the stick, wrapping her arms in the seatbelts. The car comes alive, fucking her with its bouncing hydraulics. Afterward, Alexia finds herself covered in bruises on her inner thighs and leaking oil from her vagina; sometime later, her stomach grumbles and begins to protrude. She is pregnant. Alexia’s obsession with cars might stem from her accident. Perhaps the titanium in her head has fused her perspective with the mechanical, to the extent that traditional relationships prove impossible. Consider her brief fling with Justine (Garance Marillier, star of Raw), with whom Alexia has a comical meet-cute in the auto show’s locker room shower—Alexia gets her hair stuck in Justine’s nipple ring. Later, while fooling around, she obsesses over the metal piercing and nipple’s flesh, pulling too far with her teeth beyond the pleasure-pain barrier.

Ducournau’s murderess is driven at first by the violent and sexual meeting of metal and flesh, but Titane’s just getting started. Soon there’s a string of bodies, among them her parents in an act of fiery retribution—for what, we cannot be sure. The cagey relationship between daughter and father hints at much but reveals nothing specific, aside from its emptiness. Maybe this is why Alexia finds herself drawn to and projecting upon inanimate objects. Her father’s loaded expressions suggest that he knows about her crimes, yet he does not report her. In any case, her killings threaten to catch up with her. Evading the authorities, she cuts her hair and breaks her own nose until she vaguely resembles a boy who has been missing for years. Then, after using a medical bandage to tape down her breasts and conceal her pregnant belly, she comes forward as the boy, named Adrien Legrand. Enter Vincent (Vincent Lindon), Adrien’s broken father, who allows himself to believe that his missing son has been found after all these years. Alexia has escaped an unloving father and found another who will jealously protect her.

Ducournau’s murderess is driven at first by the violent and sexual meeting of metal and flesh, but Titane’s just getting started. Soon there’s a string of bodies, among them her parents in an act of fiery retribution—for what, we cannot be sure. The cagey relationship between daughter and father hints at much but reveals nothing specific, aside from its emptiness. Maybe this is why Alexia finds herself drawn to and projecting upon inanimate objects. Her father’s loaded expressions suggest that he knows about her crimes, yet he does not report her. In any case, her killings threaten to catch up with her. Evading the authorities, she cuts her hair and breaks her own nose until she vaguely resembles a boy who has been missing for years. Then, after using a medical bandage to tape down her breasts and conceal her pregnant belly, she comes forward as the boy, named Adrien Legrand. Enter Vincent (Vincent Lindon), Adrien’s broken father, who allows himself to believe that his missing son has been found after all these years. Alexia has escaped an unloving father and found another who will jealously protect her.

Whether driven by denial or sheer loneliness, Vincent takes “Adrien” into his home and presents the young man to his other family, a band of buffed-up firefighters who live and work at a station. Doubtful glances suggest they know what their captain does not, or will not. But Vincent shuts down their skeptical remarks by introducing Adrien as “Jesus” and himself God. The station’s hierarchy may be established on the surface, but at least one firefighter begins to suspect Adrien’s real identity. In the meantime, Vincent tries to reestablish a bond with his son, who remains muted and stand-offish—in part because Alexia must conceal that she’s a pregnant woman who’s lactating motor oil. Vincent’s first attempt to bond with his son begins with an open-hearted dance to The Zombies’ song “She’s Not There,” with its telling lyrics, but the dance turns into masculine roughhousing and near-deadly violence, which puts Adrie at a distance. Vincent will have to find alternative ways of bonding with him; the usual methods that work with his firefighter bros—who love dancing with one another—don’t work.

Ducournau’s portrait of Vincent and Adrien’s growing relationship has a surprising sweetness, marked by Lindon’s nuanced performance and his character’s saddening vulnerability. Just as Alexia’s body threatens to give her away, Vincent’s body betrays him. He’s older and becoming inadequate, so he shoots steroids to maintain a Hellenistic physique. Adrien’s return gives Vincent some hope, though, and Alexia finds herself transitioning—or wanting to transition—as their father-son relationship deepens. Ducournau fashions scenes that explore their bond in both funny and touching terms. She turns an EMP call into a comic scene when Vincent teaches Adrien how to perform CPR by following the tempo of the “Macarena.” More accustomed to taking lives, Alexia feels moved by saving one. There’s also an awkward moment when Vincent finds his son trying on a dress; he laughs, then shows his new son a photo of Adrien as a boy, playing in the same dress. “They can’t tell me you’re not my son,” he says. His sincere love for Adrien in his present form welcomes empathy for this broken man, who presents a soft alternative to Alexia’s initially brutal exterior.

Titane’s undeniably feminist perspective questions heteronormativity and, in particular, the traditional bonding rituals among men by obscuring them, giving way to a tale that has been interpreted as trans-coded. Instead, Alexia’s transition into Adrien remains incomplete, while her fusion with a machine gives birth to another kind of non-binary being. But Ducournau’s remarks seem to be rooted in a feminist consideration of masculine definitions of gendered behavior and desire, suggesting that reality is far more complicated. At one point, Alexia prepares to leave Vincent because her risk of exposure becomes too great. She boards a bus to leave town, but then a group of rowdy young men talks loudly about their sexual conquests, announcing where they like to put it, and then they start harassing the one other woman on the bus. Finally, Alexia remembers what it’s like to be a woman, and she leaves and returns to her role as Adrien. Another scene at a firefighter party ends with Adrien using some of Alexia’s erotic dancing moves atop a firetruck. The dudes below look at the performance, with its curvy and snakily sexual moves, disgusted and confused over their conflicted desire. The moment is funny, of course, but it reinforces the film’s appreciation of non-binary beauty and the limitations of the male gaze.

Titane’s undeniably feminist perspective questions heteronormativity and, in particular, the traditional bonding rituals among men by obscuring them, giving way to a tale that has been interpreted as trans-coded. Instead, Alexia’s transition into Adrien remains incomplete, while her fusion with a machine gives birth to another kind of non-binary being. But Ducournau’s remarks seem to be rooted in a feminist consideration of masculine definitions of gendered behavior and desire, suggesting that reality is far more complicated. At one point, Alexia prepares to leave Vincent because her risk of exposure becomes too great. She boards a bus to leave town, but then a group of rowdy young men talks loudly about their sexual conquests, announcing where they like to put it, and then they start harassing the one other woman on the bus. Finally, Alexia remembers what it’s like to be a woman, and she leaves and returns to her role as Adrien. Another scene at a firefighter party ends with Adrien using some of Alexia’s erotic dancing moves atop a firetruck. The dudes below look at the performance, with its curvy and snakily sexual moves, disgusted and confused over their conflicted desire. The moment is funny, of course, but it reinforces the film’s appreciation of non-binary beauty and the limitations of the male gaze.

Ducournau composes her darkly transcendent film like an intimate epic of metamorphosis. Composer Jim Williams, who also created the music for Raw, delivers orchestral and choral grandiosity to scenes of abject violence and body horror. Titane is also a punishingly physical film, much as Ducournau’s last film. Not since Paul Verhoeven has violence felt so tangible and real, regardless of the sometimes fantastical circumstances. She has a way of shooting Alexia’s ravenous scratching of her pregnant belly, which begins to tear and reveal a titanium shell underneath her stomach’s half-circle, that gets under the skin. One scene features Alexia trying to perform an abortion on herself, and the sound design is enough to make one queasy. However grotesque the visual and aural presentation may sometimes be, Titane employs these potent tools—the stuff of fire, metal, sex, death, and birth—to get at something thematically elemental about how labels like “male” and “female,” often perpetuated by patriarchally established modes of understanding the world, are woefully inadequate.

A welcome affront to male fantasies and a complex rumination on identity and the human body, Titane is provocative with a purpose. Ducournau has made an incredibly original, never-saw-anything-like-it experience that, at the very least, must be cherished for its unclassifiable qualities. Fortunately, at every step of the journey, she tells her disruptive and downright insane story without delivering a mere shock machine; instead, it gives way to unexpected feelings and understanding about humanity’s many entangled states. Titane is an ambitious and singular film that will leave people stunned, awed, angry, and intrigued. For all its horror and human perspective, Ducournau argues that people prove far more complicated than any traditional uses and descriptions of the human body allow—especially those determined by the male gaze or patriarchal ideology. There’s indescribable and sublime beauty in how the body can deviate from its prescribed definitions, and there’s a profound emotional possibility when someone breaks from tradition to embrace what might be called transgressions or taboos. Improbably but wonderfully hopeful in the end, Titane celebrates the messy, ugly, and disruptive ways that people can connect when they embrace deviation.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review