Reader's Choice

Till

By Brian Eggert |

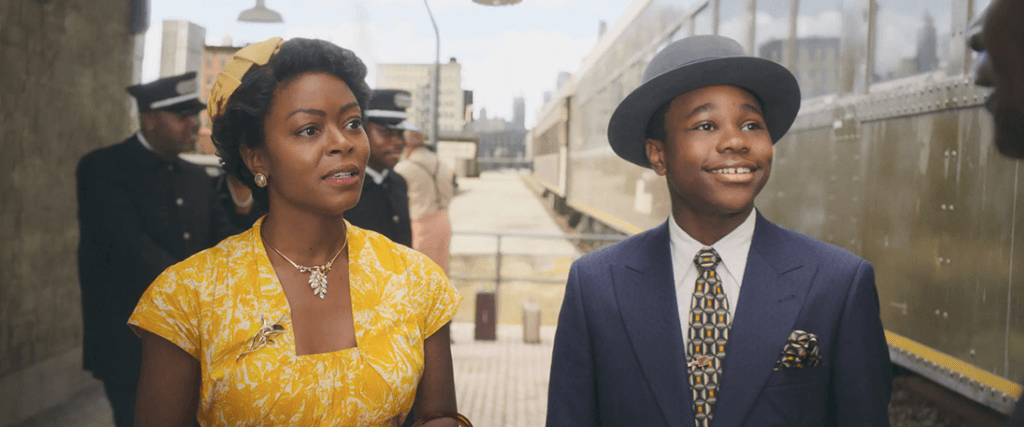

Till is a moving dramatization of Emmett Till’s lynching in 1955 and his mother Mamie Till-Mobley’s activism in the wake of her son’s death. This atrocious hate crime in the Jim Crow South reverberated throughout the Civil Rights Movement, so much so that it’s surprising this story hasn’t been turned into a major motion picture before. Although Till’s murder has been the subject of countless documentaries and books, it has never been the subject of a narrative feature. Then again, the historical account took place in a country where a grand jury refused to indict the murderers, who confessed to the crime to Look magazine not long after a jury of all white male Mississippians absolved them of any wrongdoing; where Congress didn’t enact the Emmett Till Antilynching Act until 2022; and where the very notion of thinking critically about America’s history with racism throws a segment of the population into an uproar. To be sure, it’s not altogether surprising that Till’s name goes unexamined in many American school curriculums. Doubtlessly, this will be the first time many viewers learn anything about Emmett Till. But it’s better late than never when it comes to this accessible film, which explores what happened not so long ago in a country that has changed in some ways, and in others, hasn’t changed at all.

Directed by Clemency (2019) helmer Chinonye Chukwu, who co-wrote alongside screenwriters Michael Reilly and Keith Beauchamp, Till never feels like a triumphant biopic about a civil rights figurehead. So often, movies dwell on great leaders or advocates for change in history, even those shot down in their prime, such as Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and Fred Hampton. But Emmett Till’s story doesn’t fit that mold. Instead, it’s about a 14-year-old boy (Jalyn Hall) from Chicago who’s snatched from his bed while visiting his cousins in Mississippi. He is beaten beyond recognition, shot in the head, hanged with barbed wire, and dumped in the Tallahatchie River. His story isn’t about a victory; rather, it’s a chronicle of the racial violence that was (and is) very much alive in America. The film also details how members of the NAACP encouraged Mamie (Danielle Deadwyler, from last year’s The Harder They Fall) to become a civil rights advocate, deploying images of her son’s bloated and distorted body as evidence of his lynching. It also considers what the Mississippi court chose to ignore in the case against the two white perpetrators, Roy Bryant and John William Milam.

The film opens with an idyllic scene set to The Moonglows’ “Sincerely,” where Emmett and his mother sing together in a blissful, initially carefree moment in the car. But something weighs on Mamie. She comes from a family who, along with her mother (Whoopi Goldberg) and estranged father (Frankie Faison), left the Mississippi Delta as part of the Great Migration to escape the poverty, racial prejudice, and segregationist laws of the South. Nevertheless, in the opening scenes, Mamie takes Emmett shopping to prepare for his vacation to visit his extended family in Money, Mississippi—a trip that fills her with anxiety, given that it will be the longest time she’s ever been apart from her son. Moreover, she admits to sheltering Emmett, nicknamed “Bo,” from the harsh realities of how America treats people of color, which has left him somewhat oblivious to the volatile racial dynamics in the South. So when she warns him “be small down there,” it doesn’t register as severely as it should. Instead, he remains a cheery, confident boy who doesn’t yet realize that not turning down his personality around white people in the South could mean danger.

Of course, he shouldn’t have to behave any differently. He should be able to act like a naive teenager without fear of violent or mortal repercussions. Hall portrays Emmett with all the brimming happiness and promises that a kid his age should have, though he’s unaware of how Mississippi is another world. Once there, his uncle, known as Preacher (John Douglas Thompson), and his cousins, laugh off his refusal to work alongside them in the cotton fields. To Emmett, the role of a sharecropper and the reality of picking cotton seem backward. So when Emmett is heedless of the potential consequences. The moment is like watching someone dance through a minefield. Although there’s some historical ambiguity about what happened between Emmett and Bryant, the film shows Emmett comparing her to a movie star and then wolf-whistling at her. Bryant immediately proceeds to retrieve a gun from her car, and Emmett’s cousins scramble to gather everyone and race back home. Later that night, Emmett is taken.

Of course, he shouldn’t have to behave any differently. He should be able to act like a naive teenager without fear of violent or mortal repercussions. Hall portrays Emmett with all the brimming happiness and promises that a kid his age should have, though he’s unaware of how Mississippi is another world. Once there, his uncle, known as Preacher (John Douglas Thompson), and his cousins, laugh off his refusal to work alongside them in the cotton fields. To Emmett, the role of a sharecropper and the reality of picking cotton seem backward. So when Emmett is heedless of the potential consequences. The moment is like watching someone dance through a minefield. Although there’s some historical ambiguity about what happened between Emmett and Bryant, the film shows Emmett comparing her to a movie star and then wolf-whistling at her. Bryant immediately proceeds to retrieve a gun from her car, and Emmett’s cousins scramble to gather everyone and race back home. Later that night, Emmett is taken.

In a choice that seemingly spares the viewer, Chukwu avoids depicting the violence against Emmett. Instead, the story shifts to Mamie in more ways than one. The scenes where she learns of her son’s death and must identify his body prove excruciating, with Deadwyler giving everything she has in moments that capture her character’s grief and anguish. Given Chukwu’s hesitance to show Emmett’s death onscreen, one might also assume that she will avoid his brutalized corpse. Till initially conceals the body behind foreground obstructions until, all at once, the film confronts the viewer with its horrifying reality. It’s a choice that reflects how Mamie later resolves that “The whole world has to see my son.” After identifying her son’s body, she tells reporters, “No one’s gonna believe what I just saw—they have to see this for themselves.” Encouraged by the NAACP, Mamie becomes a political figurehead for the civil rights movement, wielding the images of her lynched son as evidence to speak about the many injustices and grim realities of racist laws and inequality in America.

Till doesn’t define new standards of storytelling on film. It occupies a familiar, commercially crafted production style that presents the narrative in conventional terms. Made with a polish that will surely mean Oscar nominations, the film shines courtesy of cinematographer Bobby Bukowski, who makes even the most jarring scenes appear straightforward and confidently composed. The emotions are unambiguous and often large, allowing Deadwyler to give a terrific, pours-out-her-soul performance that’s sure to receive awards consideration. Chukwu allows Mamie’s presence to overwhelm the viewer, particularly when the prosecution and defense attorneys in the criminal case against her son’s killers cross-examine her. Chukwu and editor Ron Patane keep the camera on Deadwyler’s face throughout Mamie’s testimony—an emotionally immersive tactic. Later, when Carolyn Bryant gives her testimony and proceeds to create an elaborate story about how Emmett became aggressive with her, the camera frames the scene with Mamie’s expression of certainty that her son would never do such a thing. Elsewhere, Abel Korzeniowski’s frequently on-the-nose score supplies the intention behind every emotional beat.

Indeed, Chukwu has designed her film to reach the widest possible audience and for them to experience every scene as intended. For this, the film cannot be faulted, except to say that Chukwu takes few risks. Even so, Till is a disheartening experience, especially when watching with the knowledge that justice was never done, while the US government has only just begun to acknowledge the history of lynching in this country. For those versed in the history or co-writer Beauchamp’s documentary The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till (2005), Chukwu’s film might seem like a standard drama. But this story remains vitally necessary in America today, as political forces continue to shape what sort of history schools can teach, often with biases toward reframing and suppressing matters of race and racism. Besides, Till is also a stirring drama centered on Deadwyler’s extraordinary performance, making the film an effective way to expose unfamiliar viewers to an incident they may never have learned about in their Civics and American History classes.

(Note: This review was originally suggested on and posted to Patreon on November 30, 2022.)

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review