Reader's Choice

Thousand Pieces of Gold

By Brian Eggert |

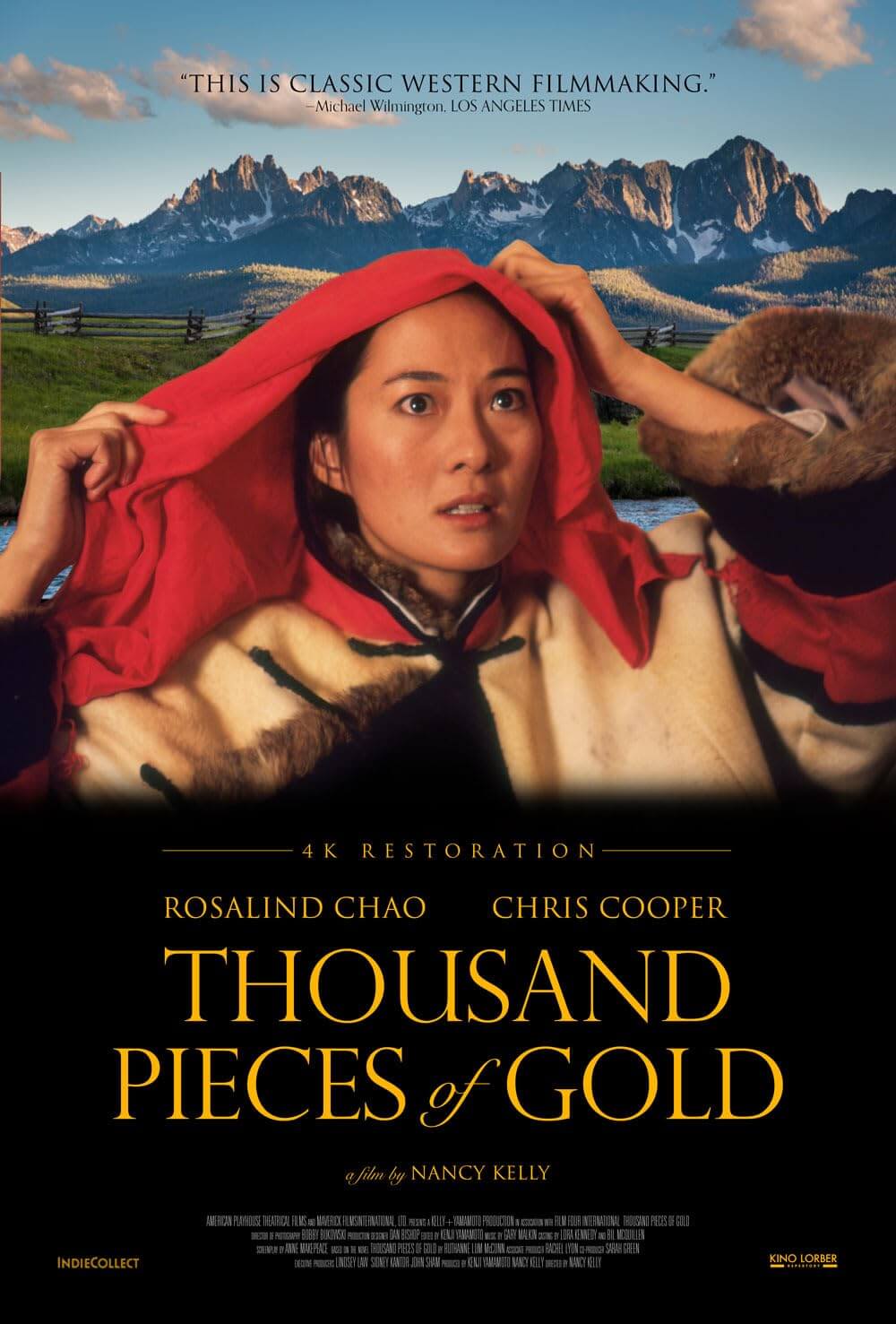

The Western film genre once encapsulated what it meant to be American. Filmmakers active during the Western renaissance—such as Anthony Mann, John Ford, Sam Peckinpah, and Howard Hawks—epitomized why no other genre better captures the ideological underpinnings of American culture. Not only did they portray cowboys bringing law to the Wild West and pioneers confronting the wilderness to carve out a new life for themselves, but also, they seldom told stories about characters outside of the white race or male gender. Just as they went overlooked in American culture, non-white races and women were often excluded, marginalized, or demonized throughout the Western genre’s prime in the early to mid-twentieth century, with few exceptions. Westerns at the time were indicative of American values by what they did not represent. It was not until 1990, when director Nancy Kelly adapted Thousand Pieces of Gold from Ruthanne Lum McCunn’s 1981 novel, that the Western genre finally acknowledged the contribution of Chinese immigrants to American identity with a film told from the perspective of a Chinese woman. If the genre has mythologized America as a land of opportunity and a place where people could demonstrate their steadfast will to achieve something greater than themselves, it often undercuts the widespread gender biases and racism that befell Chinese immigrants.

The story opens in Northern China in 1880, where Lalu Nathoy (Rosalind Chao) lives with her family during a season of droughts and despair. One day, Lalu’s father sells her for a handful of coins to support the rest of his family. Lalu is trafficked to San Francisco, where another dealer sells her to the highest bidder. Although slavery had been outlawed in the United States by this time, the practice of selling Chinese women to buyers in America continued behind closed doors for decades to follow. In Chinatown, she is purchased again by Jim (Dennis Dun), who speaks Mandarin and might be the first friendly person she meets in the New World. They will even fall in love. Except, Jim has been hired to bring Lalu to a small Idaho town built around a gold mine. Jim explains that in America, her name will be either “China Mary” or “China Polly,” and she will serve as wife to Hong King (Michael Paul Chan), a businessman who owns part of the gold mine. Hong King plans to prostitute his new wife to the locals, though Lalu’s independent streak puts a stop to that. Unlike many Chinese immigrants during this time, she refuses to be relegated to her intended role as a sex-worker. One of the first English phrases she learns is “No whore.”

Indeed, Lalu quickly learns that she is surrounded by men who want to use her body and view her race as subhuman. Only later does a Black man tell her that her enslavement to Hong King is illegal. She is free, or she should be. The notion of her freedom is reinforced by Charlie (Chris Cooper, in one of his first screen roles), a saloon owner and former Union soldier whose basic human decency calls into question why he surrounds himself with such despicable people. He confronts Hong King about Lalu, declaring, “You can’t own a person. Those days are gone.” Even so, Charlie must win her freedom in a poker game. But Lalu does not merely become Charlie’s new woman, though he loves her and gives her a room in his home. Rather, Lalu demands a chance to become independent, to make her own money, to work on a business of her own design, and to earn enough so that she can afford to join Jim and return to China. Still, Thousand Pieces of Gold adopts a romantic tradition, where our protagonist falls in love with one man, only to be compelled to another.

Indeed, Lalu quickly learns that she is surrounded by men who want to use her body and view her race as subhuman. Only later does a Black man tell her that her enslavement to Hong King is illegal. She is free, or she should be. The notion of her freedom is reinforced by Charlie (Chris Cooper, in one of his first screen roles), a saloon owner and former Union soldier whose basic human decency calls into question why he surrounds himself with such despicable people. He confronts Hong King about Lalu, declaring, “You can’t own a person. Those days are gone.” Even so, Charlie must win her freedom in a poker game. But Lalu does not merely become Charlie’s new woman, though he loves her and gives her a room in his home. Rather, Lalu demands a chance to become independent, to make her own money, to work on a business of her own design, and to earn enough so that she can afford to join Jim and return to China. Still, Thousand Pieces of Gold adopts a romantic tradition, where our protagonist falls in love with one man, only to be compelled to another.

Much of the film’s violence was not present in the novel, but even as its presence underscores the racism and savagery against Chinese immigrants in the American West, the film never becomes a polemic or history lesson. Unlike, say, HBO’s Deadwood, the film does not dwell on the ugly details by depicting them. Thousand Pieces of Gold is gentle compared to the real-life crimes committed against Chinese immigrants in the nineteenth century. In the film’s final third, the white townspeople, whom the Chinese refer to as “white devils,” rally against and exile the small population of immigrants who work in their town. Some are hung, some are threatened with fire. It’s a rare example of an American motion picture that portrays the persecution of Chinese immigrants as a tragedy. History has more examples, such as the 1885 massacre in Rock Springs, Wyoming, that left twenty-eight Chinese people dead, killed by the white locals who wanted them out of their town. Or look up the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which sought to limit the influx of Chinese immigrants and make them ineligible for citizenship. Fortunately, there’s a happy ending here. Thousand Pieces of Gold is based on a true story, and the real Lalu lived out her life with Charlie on the “River of No Return” until an old age.

Today’s viewer will recognize both the skill and limited budget behind the production. Cinematographer Bobby Bukowski knows that he only needs to point the camera at the Rocky Mountains to evoke awe; there are no elaborate camera movements to admire, only forthright scenery and well-lit interiors. Similarly, the town never looks like façades erected on a studio backlot; it has a makeshift quality, with old boards and tents, like a real mining town. Gary Malkin’s score, however, alternates between synth tones and bamboo flutes, and it rings somewhat generic—like a movie-of-the-week circa 1990. Thousand Pieces of Gold also has a quality that might be unfairly criticized as melodramatic, a word that is often misused as a pejorative. The high emotions of Anne Makepeace’s screenplay have been carefully acted by the leads. Chao and Cooper never over-accentuate their lines, bringing their characters dimension and humanity. Although Cooper would go on to become an Oscar winner, Chao has seen more exposure from her role as Keiko O’Brien on Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. This film suggests that, in an alternate universe where Hollywood saw Asian-Americans as bankable, she would have made a fantastic leading lady.

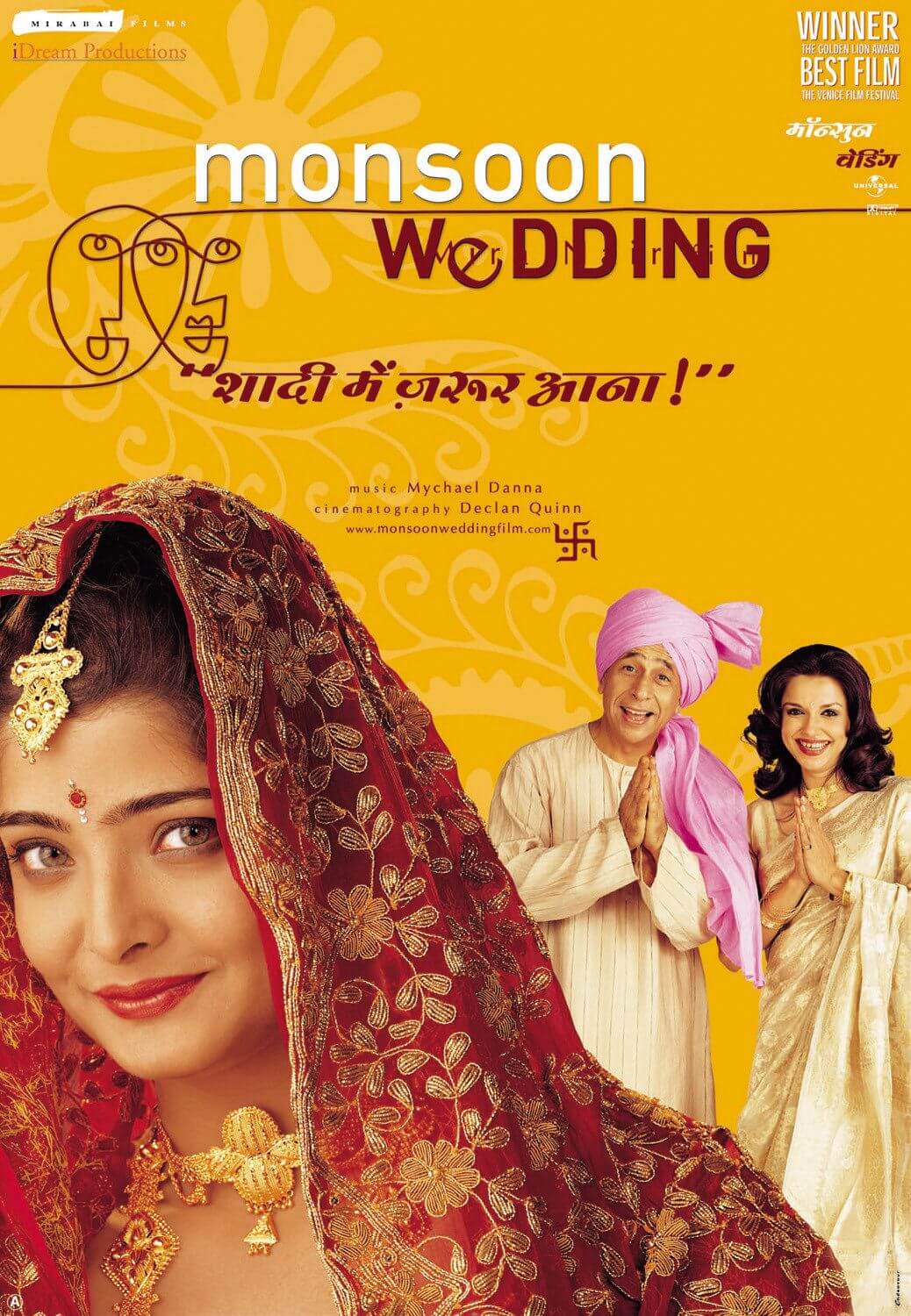

As for its director, Kelly started her career as a filmmaker with short subject documentaries about women who work on farms as ranch hands. In the mid-1980s, she discovered McCunn’s novel and chose the material for her first feature-length project. Kelly and her husband, co-producer Kenji Yamamoto, raised $3 million for the production over six years. Meanwhile, she trained at the Sundance Institute to become a dramatic filmmaker, and she was told by many Hollywood producers that a man with more experience should direct, or the story should be told from Charlie’s point of view. Conversations like this only committed Kelly to the task. The shoot took place mostly around Montana, and Makepeace’s script gave the little-known actors a chance to perform in a small-scale story that, under different circumstances, might have played like a grand romantic epic. Even the poster from the time sought to draw parallels to Gone with the Wind (1939), though it looked more like the cover of a cheap paperback.

As for its director, Kelly started her career as a filmmaker with short subject documentaries about women who work on farms as ranch hands. In the mid-1980s, she discovered McCunn’s novel and chose the material for her first feature-length project. Kelly and her husband, co-producer Kenji Yamamoto, raised $3 million for the production over six years. Meanwhile, she trained at the Sundance Institute to become a dramatic filmmaker, and she was told by many Hollywood producers that a man with more experience should direct, or the story should be told from Charlie’s point of view. Conversations like this only committed Kelly to the task. The shoot took place mostly around Montana, and Makepeace’s script gave the little-known actors a chance to perform in a small-scale story that, under different circumstances, might have played like a grand romantic epic. Even the poster from the time sought to draw parallels to Gone with the Wind (1939), though it looked more like the cover of a cheap paperback.

Despite rousing notices from critics such as Roger Ebert and Stephen Holden, with many saying Chao’s performance deserved an Oscar nomination, Thousand Pieces of Gold made less than a third of its budget at the box-office. Enduring the fate of many female directors who fail to make a splash with their first film, Kelly never made another dramatic feature. “I ran into plenty of sexism—sometimes blatant, but more often veiled,” she told IndieWire. “It never occurred to me that breaking into the film industry would be harder than breaking a horse. I was wrong.” Her film was fantastically unconventional for this period. It is neither told from the white perspective nor a man’s perspective. American films about women were rare enough; American films about women from China simply did not happen. A Chinese character with agency in a Western is a rarer thing still. Chinese immigrants usually appear in Westerns on the margins of the frame as in McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971), or on the outskirts of town, operating opium dens, as in Tombstone (1993).

Thousand Pieces of Gold confronts the West, both its history and its place in American cinema. It exposes the traditional Western as a myth, while its violence and racism against Chinese immigrants brings truth to the screen. That Kelly presents this reality within a sweeping romance makes the material all the more accessible, and all the more regretful that the film went virtually unseen in 1990. It was recently given new life by IndieCollect, a nonprofit that restores and brings awareness to forgotten works of American independent cinema. Before its 4K restoration, I had never heard of the film or its director. With any luck, it will be a new discovery for many others as well. The film’s new restoration and tour, however, has been interrupted from a theatrical re-release by the COVID-19 pandemic. Viewers can still rent the film in “virtual theaters” through Kino Lorber’s arthouse theater service, Kino Marquee. Given the impressive visual scope, one cannot help but ache over Thousand Pieces of Gold once again being robbed of its time on the big screen. For all of the frontiers it explores, it demands to be seen.

(Note: This review was selected by vote from supporters on Patreon.)

Bibliography:

Kelly, Nancy. “How Industry Sexism Stopped the Career of ‘Thousand Pieces of Gold’ Director Nancy Kelly.” IndieWire. 30 April 2020. https://www.indiewire.com/2020/04/thousand-pieces-of-gold-nancy-kelly-industry-sexism-1202228333/. Accessed 6 April 2020.

Kitses, Jim. Horizons West: Directing the Western from John Ford to Clint Eastwood. British Film Institute; 2Rev Ed edition, 2008.

McCunn, Ruthanne Lum. Thousand Pieces of Gold: A Biographical Novel. Beacon Press, 1981.

Terry, Patricia. “A Chinese Woman in the West: ‘Thousand Pieces of Gold’ and the Revision of the Heroic Frontier.” Literature/Film Quarterly, vol. 22, no. 4, 1994, pp. 222–226. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43796635. Accessed 7 June 2020.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review