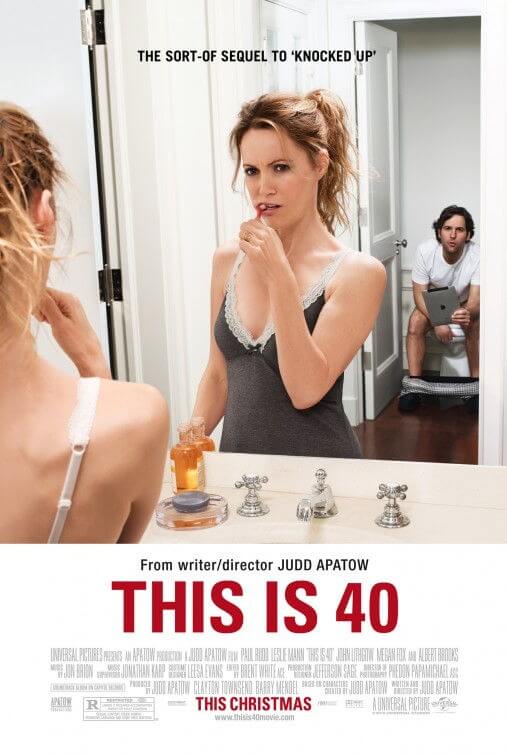

This is 40

By Brian Eggert |

Judd Apatow engages in autobiography, self-analysis, confessional, and midlife observation in This is 40, the writer-director’s comedy about a married-with-two-children couple played in part by his own wife, Leslie Mann, and his own two daughters, Maude and Iris. Apatow’s own alter-ego is Paul Rudd, that affable comedian who has appeared in most Apatow productions. For more than two hours, the film meanders about and gets lost on tangents, but wraps itself up rather nicely by the finish. Ups and downs both in the film’s plot (if you can call it that; it’s more of a rumination) and the central marriage on display make the experience grating on occasion, as Apatow seems more interested in his own world than the real world; although, there are enough bawdy laughs and relatable dramatic truths within to justify seeing this “sort-of sequel” to Knocked Up.

Debbie (Mann) was Katherine Heigl’s sister in Apatow’s 2007 comedy, and Pete (Rudd) was Debbie’s husband. As neither Heigl nor Seth Rogen appears here, there’s no need to see Knocked Up before you see This is 40, in spite of the marketing. No doubt Heigl’s public remarks about that film being “a little sexist” inspired Apatow to leave her character without so much as a cameo. At any rate, Debbie and Pete live in an impressive house with their two daughters, the teenager Sadie and the much younger Charlotte. The first scenes occur on Debbie’s fortieth birthday, although she insists that Pete use “38” on her cake because she needs two more years to accept that she’s getting older. Pairing a control freak with Pete’s more laid-back attitude, Apatow explores a series of vignettes about accepting the uncertainties of marriage with all the highs and lows, shouting matches, passion and intimacy (or lack thereof), openness, lies, and frustrations. All the while, it’s apparent he’s speaking from experience.

In addition to examining this stage of a marriage, Apatow overloads his comedy with supporting characters, some uninteresting and others very much so. A half-hour might have been spared us had Apatow resolved to cut a subplot involving Debbie’s clothing store. She suspects one of her two employees (Megan Fox and Charlene Yi) has stolen $12,000 from the store, but which one? Who cares. Fox’s annoying presence and Apatow’s ogling of her often scantily clad body serve only to give Debbie reason to doubt her own sexual attractiveness and to allow other supporting characters (Jason Segel, Chris O’Dowd, and Robert Smigel) to drool over the “eye candy.” Meanwhile, Pete runs an independent music label, and his latest client is largely forgotten Brit rocker Graham Parker, who appears as himself in a number of scenes, musical and otherwise. As nice as it was to see Parker remembered, his scenes divert from the film’s main road. Lena Dunham and Melissa McCarthy also have cameos, the latter offering the funniest end-credits outtake sequence in recent memory.

Necessary supporting roles go to Debbie and Pete’s parents, namely their fathers (both characters have virtually nonexistent mothers). An ongoing problem in Debbie and Pete’s marriage is Larry (Albert Brooks, excellent), Pete’s father, who has needed copious financial support over the years. With no sense of monetary responsibility, he’s an endearing, loving sort nonetheless, far more so than Debbie’s cold and long-absent biological father (John Lithgow), a spinal surgeon. These characters become essential to the film’s theme, being about the recurring generational relationship between children and their parents—how when children grow up, they promise themselves they won’t become like their parents, which they’re inevitably doomed to become. Accepting this process with love instead of resentment becomes the resounding message that keeps us attached to Debbie and Pete through their sometimes terrible decisions and behavior.

To be sure, it’s not impossible to conceive some moviegoers feeling unable to move beyond Debbie’s somewhat erratic behavior in the first half, or Pete’s sheer stupidity with the family’s money, or how the two repeatedly say horrible things to one another only to make up shortly thereafter. Most frustrating is watching as they talk about their money problems while Pete cries in his BMW and Debbie drives home in her Lexus. Their house must be worth a few million too. How rough they have it! Anyway, Apatow generates little sympathy for people who lament their budgetary problems when the film leads up to a lavish, catered birthday party. Their home is loaded with iPads and iPhones and the latest technology; modern diets and exercise routines with a personal trainer fill family discussions; their children complain about possibly having to use non-wifi internet connections. Whether Apatow meant all this ironically or not remains unclear, as no doubt, he and his family live in a similar home, but what’s certain is that he assures a certain portion of his audience won’t be able to relate to these rather spoiled people.

Nevertheless, This is 40 contains enough truth about marriages and families to outweigh the irritating details of the family’s financial situation and the film’s seemingly aimless structure. For what may be his most personal picture, Apatow brings together his friends and family in a comedy that feels delivered straight from the heart, with a sharp study of the family dynamic from one generation to the next. Included are the usual Apatow-production moments of bawdy, blue-humored raunch and potty-mouthed antics to lighten the material. But the filmmaker also manages to bring out some fine, very complex performances from his wife and daughters. By the end, Mann’s difficult-to-like character wins us over, flaws and all, just as the film does. This is 40 is much like the marriage depicted within: Undisciplined and sometimes wandering, yet populated by characters who become so likable and true that we cannot help but stay with them to the end.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review