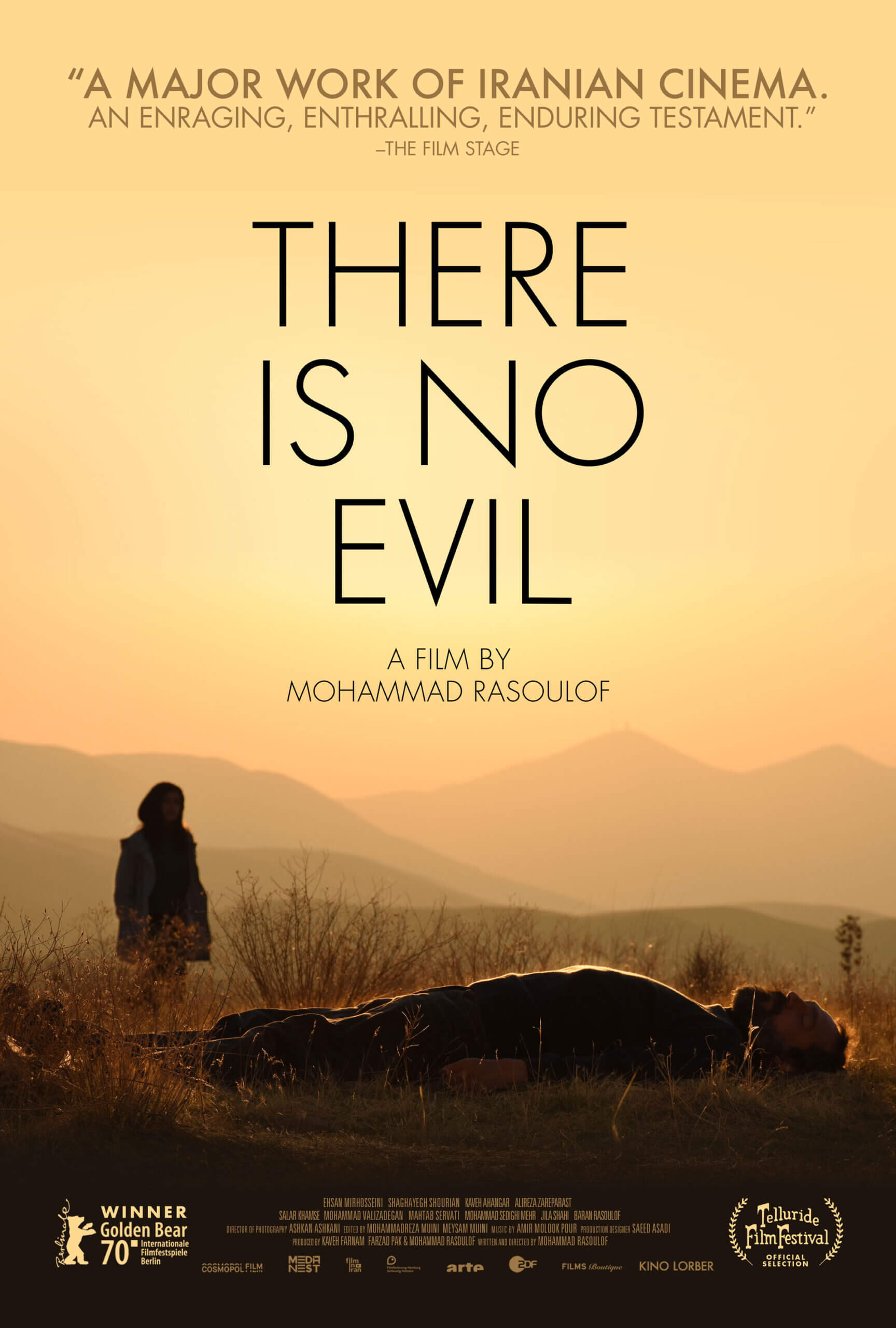

There is No Evil

By Brian Eggert |

Mohammad Rasoulof’s There is No Evil considers how the Islamic Republic of Iran has used forced military service and state-sanctioned executions to maintain control since the 1979 Revolution. To qualify for a passport, insurance, trade licenses, or to leave the country, men must serve up to two years of mandatory military service. During that time, they may be asked to carry out executions of criminals or political dissidents. (Iran is believed to be the country with the highest execution rate after China.) Many of those who perform their service live normal lives in Iran; some leave the country afterward to find opportunities elsewhere. But most carry out their conscription because the law requires it, and to refuse could mean prison time and a stain on their family’s reputation from the state’s perspective. To confront these issues, Rasoulof’s approach is far from a didactic drama that lays them bare. Then again, compared to other Iranian filmmakers who often rely on allegory to address larger social issues, Rasoulof’s subject matter is direct. The Iranian filmmaker’s profoundly human four-part anthology deals with the morality, compartmentalization, and lasting impact of people forced to participate in Iran’s death penalty. And yet, he never resorts to making an outright statement; rather, he weighs the human costs, and the implications become unmistakable.

The film is not only a humanist statement but an act of courage. When the film received the Golden Bear for best feature at the Berlin International Film Festival in February 2020, Rasoulof could not attend. He has been banned from making films and saddled with a one-year prison sentence for spreading “propaganda against the system.” After his 2010 arrest for shooting without a permit, his films Manuscripts Don’t Burn (2013) and A Man of Integrity (2017) angered the government, and they barred him from filmmaking or leaving the country; he was also sentenced to a year in prison, which, so far, goes unserved. Despite the attention on him from the Iranian state, he filmed There is No Evil in secret, and many of the film workers involved risked their safety and freedom by taking part. But unlike other films shot illegally, this one does not bear a guerilla-style appearance. It doesn’t look like Rasoulof snuck out into the dead of night with his cast and crew to steal a few shots. Instead, the film appears elegantly composed and considered, offering scenes in crowded city streets and idyllic countryside locations. The filmmaking is patient, often stunningly shot by cinematographer Ashkan Ashkani, and leisurely paced for full immersion in the grave situations in each story.

Discussing the content and structure of the film in any detail means revealing what has been designed to surprise you. Consider yourself warned of spoilers in the next few paragraphs. There is No Evil doesn’t announce its subject in the first episode. It follows Heshmat (Ehsan Mirhosseini), an average guy with a mundane routine. He returns home from work and showers, unwinding with some television and a snack. Heshmat is a decent man, evidenced by how he helps some children free a cat stuck behind some equipment. Then he leaves to pick up his wife from work and daughter from school. They shop for groceries as a family, stop by his mother-in-law’s to clean and feed her, and go out for pizza. After going through their routine, Heshmat falls fast asleep. His alarm goes off in the middle of the night. He wakes and drives to work in the rain, but something about the traffic lights that switch from red to green makes him freeze. We must reconsider his entire day after the final moments of his story, when, inside a cramped office, Heshmat prepares himself coffee and fruit before signal lights on a wall indicate that prisoners are ready. Then, by pressing a button, he executes several men in the same instant.

Discussing the content and structure of the film in any detail means revealing what has been designed to surprise you. Consider yourself warned of spoilers in the next few paragraphs. There is No Evil doesn’t announce its subject in the first episode. It follows Heshmat (Ehsan Mirhosseini), an average guy with a mundane routine. He returns home from work and showers, unwinding with some television and a snack. Heshmat is a decent man, evidenced by how he helps some children free a cat stuck behind some equipment. Then he leaves to pick up his wife from work and daughter from school. They shop for groceries as a family, stop by his mother-in-law’s to clean and feed her, and go out for pizza. After going through their routine, Heshmat falls fast asleep. His alarm goes off in the middle of the night. He wakes and drives to work in the rain, but something about the traffic lights that switch from red to green makes him freeze. We must reconsider his entire day after the final moments of his story, when, inside a cramped office, Heshmat prepares himself coffee and fruit before signal lights on a wall indicate that prisoners are ready. Then, by pressing a button, he executes several men in the same instant.

Rasoulof’s unassuming style carries the themes from one story to the next. Although the characters remain different, their stories are the same, suggesting that the same concerns face anyone conscripted into military service. The second story, called “She Said ‘You Can Do It,’” follows Pouya (Kaveh Ahangar), a death row guard stirred in the middle of the night to carry out his grim duty. Except, the anxious Pouya, sleeping alongside five bunkmates, grapples with what he must do. The others have already performed executions, and they try to assure him that the victim’s crimes justify their death. But Pouya’s conscience leaves him rattled and sick. He resolves to arm himself and escape service at gunpoint, declaring, “I don’t want to kill anyone, but if I have to, I’ll shoot any person forcing me to execute someone.” He has dreams of moving to Austria, where his girlfriend plans to study music, but those plans will mean nothing if he has to kill someone to achieve them.

Javad (Mohammad Valizadegan), the protagonist of the third story, has come to a different rationalization. In exchange for a three-day leave to visit his girlfriend Nana (Mahtab Servati) for her birthday, Javad has executed someone. His choice proves fateful when he arrives to discover the birthday celebration has been put on hold for a funeral service of a local teacher. What might seem like a predictable twist is elevated by Rasoulof’s staging of the reveal in an idyllic setting, surrounded by flowers, lush greens, and a cheerful birthday dance.

The final story, entitled “Kiss Me,” is less obviously connected to the others at first. Nevertheless, its final moments reveal how Rasoulof’s overall structure to There is No Evil has implications that affect people for their entire lives. When a medical student, Darya (Baran Rasoulof, the director’s daughter), visits her uncle and aunt, Barham (Mohammad Seddighimehr) and Zaman (Jila Shahi), at the behest of her off-screen father, she does not know why she’s there. Barham and Zaman live in seclusion without a phone or internet; they survive from solar panels and beekeeping. Barham also serves as a local doctor, although he has no clinic. The lingering secret as to Darya’s reason for being there suggests what might’ve become of Pouya in twenty or thirty years—and what might happen to anyone who abandons their service after making such a moral choice. In each of these stories, something insidious resides beneath seemingly banal services. Some might call that evil, a term that evokes a moral or even religious certainty in the dichotomy between good and evil. It seems more complex than anything purely one way or the other. If there is no evil, then there is only the law that forces these men to make a choice.

None of these stories address whether those executed were guilty or innocent of breaking Iranian laws, or whether they deserved to face the consequences. Instead, the final story offers a parable about the value of all life, referenced by a farmer who refuses to kill a fox, even though the predator has made it impossible to keep chickens. Rasoulof argues that the ends never justify the means, that the taking of life does not reinforce the law. While the particulars of Iran’s justice system remain at a remove, Rasoulof acknowledges the country’s preferred mode of execution: hanging. The executions take place behind closed doors in the first two stories, usually in a sub-sub-basement devoid of windows and composed of colorless concrete walls and corridors. The first story shows the executioner pressing a button from behind glass to carry out multiple sentences—a shocking moment that sets the mood of the remaining runtime. In other cases, characters reference having to pull the stool out from beneath the victim’s feet, leaving them to fall with a noose around their neck. Some justify the action as “following orders.” Another rationalizes, “Right or wrong, this is the law of the land.” Yet another character notes, “This is Iran. There’s no law here. Just money and nepotism.”

None of these stories address whether those executed were guilty or innocent of breaking Iranian laws, or whether they deserved to face the consequences. Instead, the final story offers a parable about the value of all life, referenced by a farmer who refuses to kill a fox, even though the predator has made it impossible to keep chickens. Rasoulof argues that the ends never justify the means, that the taking of life does not reinforce the law. While the particulars of Iran’s justice system remain at a remove, Rasoulof acknowledges the country’s preferred mode of execution: hanging. The executions take place behind closed doors in the first two stories, usually in a sub-sub-basement devoid of windows and composed of colorless concrete walls and corridors. The first story shows the executioner pressing a button from behind glass to carry out multiple sentences—a shocking moment that sets the mood of the remaining runtime. In other cases, characters reference having to pull the stool out from beneath the victim’s feet, leaving them to fall with a noose around their neck. Some justify the action as “following orders.” Another rationalizes, “Right or wrong, this is the law of the land.” Yet another character notes, “This is Iran. There’s no law here. Just money and nepotism.”

If these examples are any indication, Rasoulof’s screenplay sometimes uses dialogue that puts a fine point on his themes or perspective. His approach is unlike the late Abbas Kiarostami, who disguised his nationalized critique in ambiguous scenarios that raised moral conundrums, often using children to minimize and also universalize their questions. His shorts Two Solutions for One Problem (1975) or First Case, Second Case (1979) remain essential prompts for an entrenched discussion. Alternatively, Asghar Farhadi uses intricate domestic dramas, most famously in A Separation (2011), to allegorize his critique of Iran’s repressive culture. And even Rasoulof has used more ambiguous methods in the past. Watch Iron Island (2009), about the captain of a rusty, broken-down tanker teeming with people who follow his every order, despite their immobile conditions. Besides the title, There is No Evil seems to have disposed of irony and metaphor to face the problem in terms that will be unmissable for his audience—a largely international viewership since the film was banned in Iran.

Questioning Iran’s laws, and sensitive to how capital punishment has a ripple effect beyond the act itself, There is No Evil uncovers how the state has penetrated the culture and left something deeply wrong at the center. It’s not a matter of religious or political ideology in the strictest sense, but something far more universal than one might expect, making the Farsi-language drama necessary viewing alongside other, similarly themed stories about the death penalty, including Werner Herzog’s Into the Abyss (2011) or Chinonye Chukwu’s Clemency (2019). It’s also a rare film anthology that feels like a cohesive and carefully structured whole instead of a loosely affiliated series of stories. More specifically, Rasoulof shows how the average citizen in Iran has no choice at all. You can either carry out executions or risk breaking the law by fleeing service; you can resign yourself to follow the law or choose resistance. Iranian law and military conscription leave people in a no-win scenario, and Rasoulof’s tales reflect on how leaving people with no choice eats away at their humanity. There is No Evil should be sought out and seen, if not for its thoughtful and affecting drama, then to support Rasoulof’s continued project of clandestine filmmaking and defiance.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review