Their Finest

By Brian Eggert |

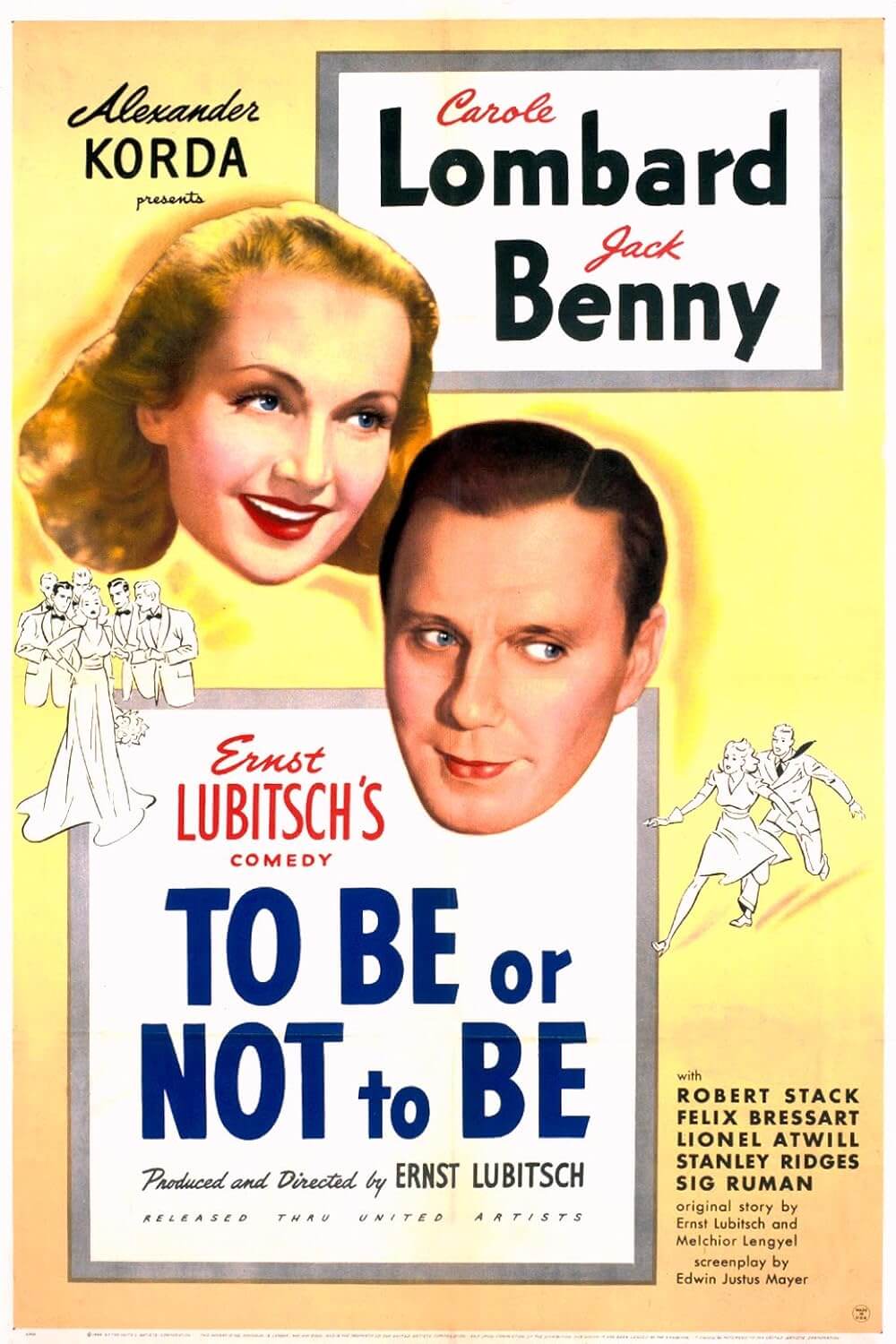

Americans find it all too easy to forget their late entry into World War II. Consider the Blitz, a series of months in which the British endured devastating air raids from Hitler’s Germany. Industrial and metropolitan targets throughout England suffered bombing that left thousands dead; meanwhile, America maintained an isolationist stance toward Hitler’s reign, at least until the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. At the same time, Hollywood and the British film industry alike tried to instill a steadfastness in the British people and convince Americans to intervene, and yet do so in a way that didn’t feel like propaganda. Films like Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator, Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent, Fritz Lang’s Man Hunt, and Carol Reed’s Night Train to Munich each beckoned Americans to beware the looming threat of fascism and help defend the world from its tyranny. Filmmakers passionate about their cause put a face to the conflict, suggested victory through bravery, called the uncommitted to arms, and delivered the message in entertaining and artistic ways.

Call the tactic “authenticity informed by optimism”—the words used by the British Ministry of Information’s film division in Their Finest, when they instruct a group of writers and producers to make a multifaceted piece of wartime cinema. The title comes from Winston Churchill’s 1940 speech anticipating the Battle of Britain; he hoped they would look back and say, “This was their finest hour.” Based on the 2009 novel Their Finest Hour and a Half by Lissa Evans, the film tackles serious subject matter, especially given its setting of London in 1940, though the material contains a blithe romantic comedy component and surprising humor throughout. It also hits several touchpoints that, admittedly, remain soft spots for this critic: stories about WWII, films about the film industry, and atypical romantic comedies pique my interest. Their Finest has all three. But this would be an exceptional film even without my predilection for the material. Danish director Lone Scherfig captures everything her characters aspire to create, with the added bonuses of a feminist message and informed historical context.

A Welshwoman barely scraping by in London during the Blitz, Catrin Cole (Gemma Arterton) looks for work while her painter husband (Jack Huston) fills canvasses with grim depictions of bombed-out factories. Fortunately, she can support them both after landing a post at the Ministry of Information’s film division. Her supervisor (Richard E. Grant) soon learns of her newspaper experience and promotes her to a screenwriter of “slop”—an outdated industry term for women’s dialogue. She’s paired with two seasoned writers, Raymond Parfitt (Paul Ritter) and the egoist Tom Buckley (Sam Claflin), on a new picture with not-so-modest ambitions: Not only must the filmmakers inspire women at home, but they must also bolster their men and convince Americans to join the war effort. It’s all ordered by Jeremy Irons’ stodgy Secretary of War, who gives a dense rendition of Henry V’s “St. Crispin’s Day” speech to the crew’s rolling eyes.

Before long, their based-on-a-true-story—about twin sisters who stole their drunken father’s boat and ended up helping in the evacuation of Dunkirk—transforms to support the production’s agenda. Soon there’s a chummy, soused uncle; a cute dog; an unlikely romance with an injured British hero; and a good-looking American aboard the sisters’ boat. Their Finest offers an insider’s view into how the typical studio programmer (a fictional effort called “The Nancy Starling”) goes from concept to screen, from casting to writing, all the way to the premiere. Characters like Bill Nighy’s scene-stealing Ambrose Hilliard, an aged actor passed his prime (think Nighy’s role in Love, Actually), enliven the material into both a raucous comedy and bittersweet drama. For instance, a subplot involves Hilliard’s agent (Eddie Marsan) succumbing to the Blitz, only to be replaced by his hard-nosed sister (Helen McCrory), who must convince the rather vain Hilliard of his actual age. Elsewhere, Catrin and Tom must write-in a role for an American war hero named Carl (Jake Lacy) to involve American moviegoers.

Before long, their based-on-a-true-story—about twin sisters who stole their drunken father’s boat and ended up helping in the evacuation of Dunkirk—transforms to support the production’s agenda. Soon there’s a chummy, soused uncle; a cute dog; an unlikely romance with an injured British hero; and a good-looking American aboard the sisters’ boat. Their Finest offers an insider’s view into how the typical studio programmer (a fictional effort called “The Nancy Starling”) goes from concept to screen, from casting to writing, all the way to the premiere. Characters like Bill Nighy’s scene-stealing Ambrose Hilliard, an aged actor passed his prime (think Nighy’s role in Love, Actually), enliven the material into both a raucous comedy and bittersweet drama. For instance, a subplot involves Hilliard’s agent (Eddie Marsan) succumbing to the Blitz, only to be replaced by his hard-nosed sister (Helen McCrory), who must convince the rather vain Hilliard of his actual age. Elsewhere, Catrin and Tom must write-in a role for an American war hero named Carl (Jake Lacy) to involve American moviegoers.

The writing process is not inherently cinematic. Luckily, viewers don’t have to endure long stretches of Catrin or Tom sitting at a typewriter. The film shows us the moments when things go wrong, such as the first take of Carl’s performance when he looks directly at the camera and smiles. These minor disasters require sharp minds, wit, and creative thinking to overcome. After their shoot is nearly completed, the filmmakers receive a note from their distributors across the pond—their picture reads as decidedly too British (i.e. restrained) and, in order to secure their film for American audiences, they’ll need an ending with a bang (Americans do not like subtlety). Each addition or change requires a new last-minute draft by Catrin and Tom, who, of course, begin to fall for each other in their collaboration. The romance emerges gradually from the meet-cute of their creative head-butting and, much to our shock, ends in an unexpected way—but in a manner that deepens the material from its sometimes farcical setup. After titles like Byzantium or Tamara Drewe, Arterton once again demonstrates her ability to portray complex characters who confront their otherwise regimented and marginalized roles as women. She’s a compelling lead, yet her character retains a convincing, and appropriate, authenticity.

Moreover, by avoiding a squeaky clean happy ending that fades to black on a lovers embrace, screenwriter Gaby Chiappe maintains the distinction between real-life and cinematic artifice. “People love films because they provide a structure to life,” says Tom. Though “The Nancy Starling” production offers its share of pleasant diversions, Their Finest never allows the viewer to forget that the rampant bombings meant unexpected death and tragedy. The endless series of on-set hitches is offset by the reality of the war. Production designer Alice Normington challenges last year’s Allied in its stirring details of wartime London. A particularly scarring sequence involves Catrin surviving when a storefront explodes behind her; she searches for other survivors and is horrified to find body parts everywhere—the limbs of mannequins, mostly, until she finds a human victim in the rubble.

Scherfig balances what in another director’s hands could be an uneven mixture of tones, carefully maneuvering around the pervasive wartime trauma to find romantic, funny, and touching moments. Cinéastes and fans of classics will appreciate the attention to detail throughout, from the costumes (both behind and in front of the camera) to the equipment. Beyond its behind-the-scenes depiction of a 1940 film production, Scherfig replicates several fun sequences of “The Nancy Starling” that look and feel like a studio picture from this era, evoking undeniable nostalgia. But the personal relationships at the center drive the narrative, while the formal flourishes, sense of history, and apparent love of cinema enrich it. To be sure, Their Finest is a charmed film that manages to be everything the film-within-a-film sets out to achieve—it’s entertaining, inspiring, provides substantial feminist and wartime commentaries, and reminds American audiences that the British fought Hitler long before 1941.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review