Theater Camp

By Brian Eggert |

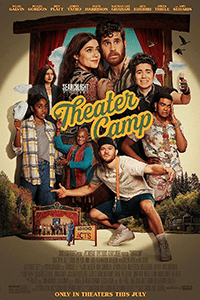

For drama kids, dance studio performers, musical enthusiasts, and arts educators, Theater Camp will instill moments of recognition and humor. Made by performers from Broadway’s Dear Evan Hansen and its big-screen adaptation, the film details both the unique experience of theater camp for those familiar and offers a glimpse of this strange microcosmos for the uninitiated. Although the scrappy conditions, single-minded passions, brutal auditions, egomaniacal instructors, and resulting haphazard stage productions may seem alternately miserable and delightful from an outsider’s point of view, the staff and committed attendees know how to “turn cardboard into gold.” Everyone’s there because they love what they’re doing, and that’s catching, even for someone with no theater experience. Still, this affectionate portrait of a distinct community and the eccentric types therein crams too much into a short runtime, suggesting the filmmakers started out with much more footage and cut too deep, leaving a mangled result.

Conceived by co-directors Molly Gordon and Nick Lieberman, who co-wrote their screenplay with Noah Galvin and Ben Platt, Theater Camp expands on their 2020 short of the same name. The filmmakers clearly draw from Christopher Guest’s output, adopting a mockumentary format, for better or worse. The device informs the structure and aesthetics, with d.p. Nate Hurtsellers using handheld digital cameras that create the convincing look of grainy 16mm film stock and capture the mostly improvisational action. Meant to evoke a vérité technique whereby no documentarian appears onscreen, the film annoyingly interrupts the action with white titles on a black screen, offering context, with almost omniscient knowledge into characters’ motivations. Aiming for a combination of Waiting for Guffman (1996) and Wet Hot American Summer (2001), the film’s satiric quality might have landed, except the filmmakers never quite justify the mockumentary framework. When not one attention-hungry kid looks at the camera, it borders on suspicious, suggesting the filmmakers either didn’t commit themselves to the conceit or simply added the titles after the fact.

“This place is for people who need it,” announces one character of AdirondACTS, the upstate New York summer retreat struggling to keep afloat under the committed management of its founder, Joan (Amy Sedaris). Around her, an established company of creatives orbits, oblivious to the scraping-by required to keep the camp operating. But after Joan succumbs to a coma following a seizure (prompted by a strobe light at a school production of Bye Bye Birdie), the management of the camp falls to her son, Troy (Jimmy Tatro, from Netflix’s American Scandal). A YouTube finance guru with bro energy, Troy is determined to prove he can “take a business from late to lit”—even though he needs to look up the meaning of “repossession.” While serving as a portrait of the camp’s teachers and students, the film’s conflict hinges on whether Troy can save the camp from the bank. Though Theater Camp is about outsiders in a self-contained world of expression, it’s also about underdogs using art to sustain themselves.

Troy becomes the entry point for those unfamiliar with the theater camp experience and remains amusingly oblivious to the decorum and lingo. When the technical director Glenn (Galvin) explains the camp will put on a combination of straight plays and musicals, Troy asks, “So what’s a gay play?” Glenn pauses, “That’s a musical.” At first, Glenn may seem like a sidelined character next to the costume designer Gigi (Owen Thiele), dance teacher Clive (Nathan Lee Graham), and the codependent Amos (Platt) and Rebecca-Diane (Gordon), who specialize in music theory and drama, respectively. But Glenn becomes more important later, stealing the show, as it were. Meanwhile, the children characters prove underdeveloped, used mostly for laughs in the juxtaposition of their diminutive size and capacity to perform in complex, mature emotional scenarios for the stage. Rather, much of the story hovers around Amos and Rebecca-Diane. The former describes himself as “A performer who works full time as an acting teacher,” while the latter teaches a past lives regression class and calls music “the closest thing we have to the Other Side.”

Troy becomes the entry point for those unfamiliar with the theater camp experience and remains amusingly oblivious to the decorum and lingo. When the technical director Glenn (Galvin) explains the camp will put on a combination of straight plays and musicals, Troy asks, “So what’s a gay play?” Glenn pauses, “That’s a musical.” At first, Glenn may seem like a sidelined character next to the costume designer Gigi (Owen Thiele), dance teacher Clive (Nathan Lee Graham), and the codependent Amos (Platt) and Rebecca-Diane (Gordon), who specialize in music theory and drama, respectively. But Glenn becomes more important later, stealing the show, as it were. Meanwhile, the children characters prove underdeveloped, used mostly for laughs in the juxtaposition of their diminutive size and capacity to perform in complex, mature emotional scenarios for the stage. Rather, much of the story hovers around Amos and Rebecca-Diane. The former describes himself as “A performer who works full time as an acting teacher,” while the latter teaches a past lives regression class and calls music “the closest thing we have to the Other Side.”

The filmmakers know these personalities through and through. They pour every observation about their community into this little film, making the narrative feel secondary and the 94-minute runtime feel consumed by random asides. While the faculty attempts to stage an original musical written by Amos and Rebecca-Diane called Joan, Still, in honor of the camp’s comatose founder, Troy finds himself conned into making a deal with a competing rich-kid theater camp, repped by Caroline (Patti Harrison). They have long sought to buy out the AdirondACTS, and Troy makes the deal, only to regret it. But this conflict falls flat, with little doubt that the camp will overcome its financial troubles, despite its inept new manager. The film might have been better served by dispensing with the contrived plot and going with a purely observational portrait that conveys why Joan fell in love with youth theater in the first place. Instead, few characters receive full arcs, though viewers well-versed in these personalities may overlook the story’s deficiencies because they recognize the stereotypes on display.

If you’ve seen one quirky camp comedy with heart, you’ve seen them all. By the end, the teachers and students save the camp, put on a rousing show, and defy all odds, all while celebrating each others’ individuality and idiosyncrasies. The film offers plenty of laughs in editor Jon Philpot’s patchwork assembly, from Rebecca declaring “tear sticks are doping for actors” to the faculty demanding the young performers imagine “the reality of IBS.” Theater Camp will work well for its target audience, even if its foursome of writers and directing duo don’t have a handle on the mockumentary format. More often than not, the material lovingly mocks its characters and encourages us to laugh at these particular behaviors rather than giving them emotional integrity, which feels like a disservice. Regardless, the film was reportedly a crowd-pleaser at the Sundance Film Festival this year, prompting Searchlight Pictures (formerly Fox Searchlight) to acquire it for distribution. Indeed, the momentary distractions are plenty, but on the whole, the film doesn’t amount to much.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review