The Zone of Interest

By Brian Eggert |

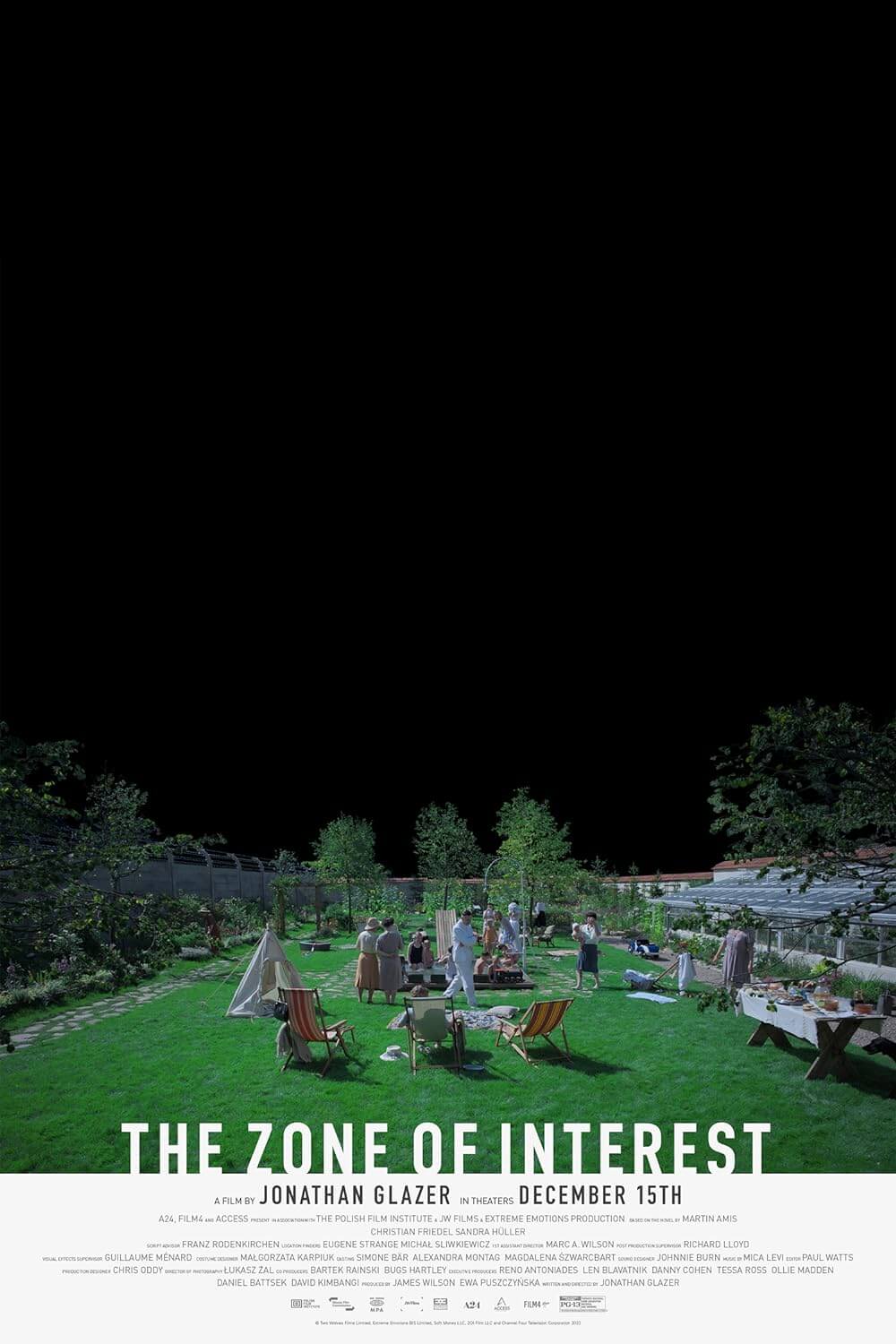

The Zone of Interest’s white title bursts onto a black screen with blinding intensity. Gradually, the title fades into grays before leaving the spectator in an all-consuming darkness. For a prolonged period, only obscure sounds and Mica Levi’s haunting score occupy the void. As title treatments go, this deceptively simple one lingered in the back of my mind throughout Jonathan Glazer’s new film, about a Nazi officer whose family lives next to Auschwitz, either willfully oblivious of, immune to, or uncaring about what unfolds less than a hundred yards away. The title sequence visualizes how society’s outrage and shock quickly fade into apathy in the face of the world’s immeasurable brutality. The instant news cycle and the sheer volume of heinous acts normalize atrocity, making it all too easy to turn away and focus on the particulars of our everyday lives. When news about some horrible event breaks, it’s everywhere and unavoidable. But slowly, our attention shifts elsewhere, hyper-focused on what’s right in front of us, while those affected don’t have that luxury. Glazer’s disquieting film remarks on the dehumanization of the Holocaust, but it also clashes with the long-held belief that the Holocaust was an incomprehensible event orchestrated by mythologically evil forces. Instead, it shows that people with familiar and relatable concerns about building a home and family perpetrated these acts. Glazer has made one of the most honest depictions of humanity’s vile limits ever made.

Much debate surrounds the ethics and politics of representing the Holocaust on film. A particular line of thinking suggests that no film can adequately capture the genocide’s monumentality, and when films such as Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993) attempt to do so, they only minimize its unfathomable scope. Worse, a narrative treatment risks trivializing or creating a distancing effect from the actual event, containing its reality in a dramatic representation with potential historical inaccuracies. Should the Holocaust be represented by cinema’s inherent poetry and entertainment value? Documentarian Claude Lanzmann argued that it should not, having made the essential documentaries on the topic, including the nine-hour Shoah (1985), which consists almost entirely of interviews with victims, perpetrators, and witnesses. Glazer’s film does not attempt to dramatize the Holocaust as other films but rather characterizes the mindset that engineered it and allowed it to continue. The film presumes an awareness of the Holocaust and its consequences—which, given that more than half of all US states do not require education on the subject, is perhaps a faulty assumption. But its purpose is not to address all aspects in a single film or even dramatize one episode. Glazer’s ambition with The Zone of Interest is far more artistic, complex, and confronting.

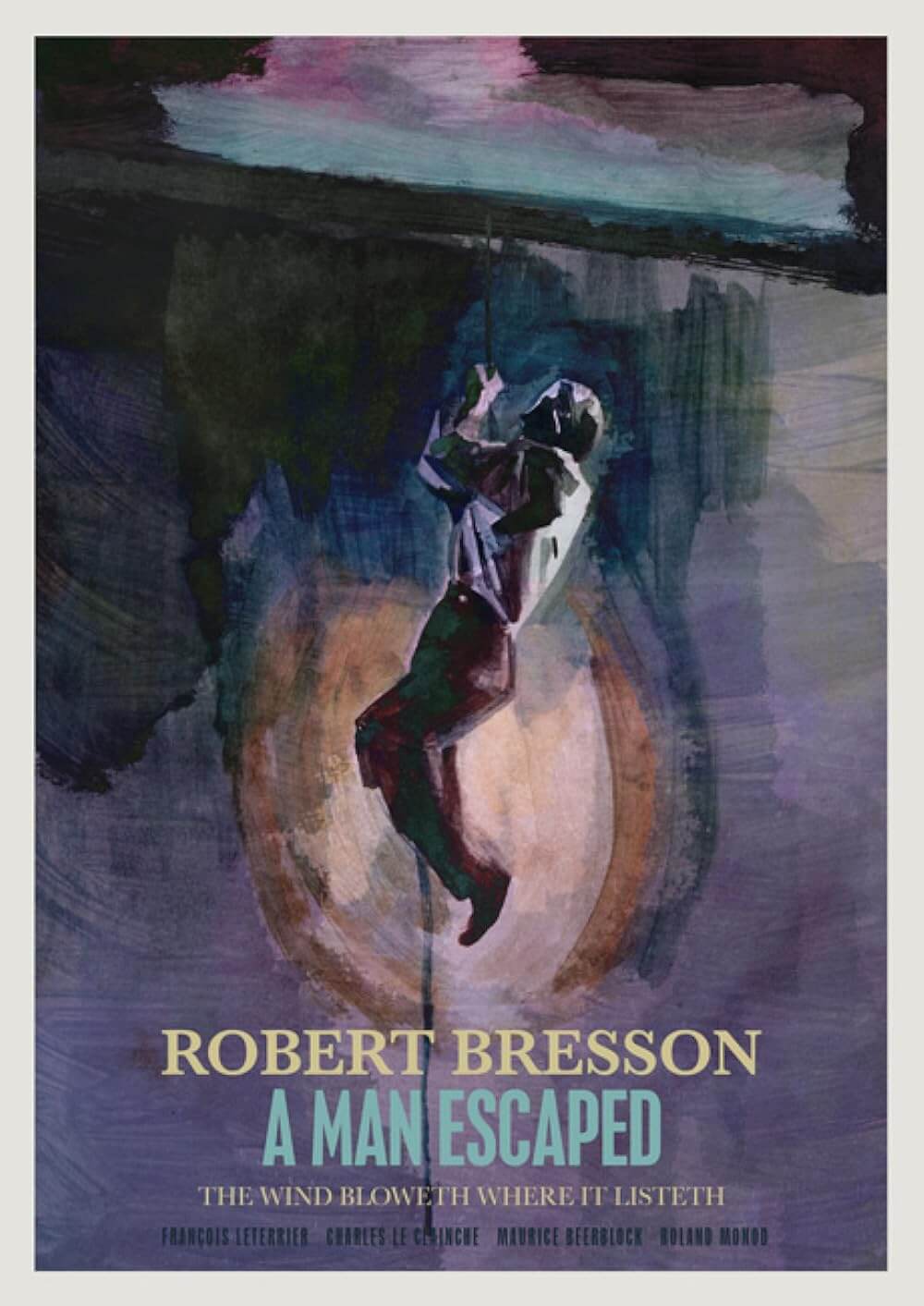

A loose adaptation of the 2014 novel by Martin Amis, Glazer’s script takes what were fictionalized roles in the book and gives them historical backing. Central is Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel), the real-life SS commandant who oversaw the torture and death of over one million people, primarily Jews, at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. Omitting much of the novel’s story, Glazer, similar to his 2013 adaptation of Michel Faber’s 2000 book Under the Skin, uses the book as a launchpad for something completely different—a specific and exacting treatment of a singular idea, albeit fleshed out with a portrait of humanity. A measured study in the banality of evil, The Zone of Interest opens with Rudolf and his wife Hedwig (Sandra Hüller) out for a picnic and swim with their children and servants, the idyllic scene unfolding by a river, surrounded by lush greens and rolling forest hills in the backdrop. Shot in wide masters, the framing is expansive, asking the viewer to consider more than the characters within. And sure enough, an aural curiosity lies beneath this peaceful image and, once noticed, becomes deafening and unshakable: the faint pops of gunfire, the occasional scream, and the persistent industrial hum of the crematorium.

A loose adaptation of the 2014 novel by Martin Amis, Glazer’s script takes what were fictionalized roles in the book and gives them historical backing. Central is Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel), the real-life SS commandant who oversaw the torture and death of over one million people, primarily Jews, at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. Omitting much of the novel’s story, Glazer, similar to his 2013 adaptation of Michel Faber’s 2000 book Under the Skin, uses the book as a launchpad for something completely different—a specific and exacting treatment of a singular idea, albeit fleshed out with a portrait of humanity. A measured study in the banality of evil, The Zone of Interest opens with Rudolf and his wife Hedwig (Sandra Hüller) out for a picnic and swim with their children and servants, the idyllic scene unfolding by a river, surrounded by lush greens and rolling forest hills in the backdrop. Shot in wide masters, the framing is expansive, asking the viewer to consider more than the characters within. And sure enough, an aural curiosity lies beneath this peaceful image and, once noticed, becomes deafening and unshakable: the faint pops of gunfire, the occasional scream, and the persistent industrial hum of the crematorium.

Glazer observes the horrific reality of the Höss family’s common lives, their home sharing a wall, topped by barbed wire, with the Auschwitz camp. Rudolf spends his days at work, taking meetings and making plans to improve the efficiency of their murder factories. Meanwhile, Hedwig, a mother of five children, her eldest boy in the Hitler Youth, labors over her elaborately designed garden and pool while her servants manage the cooking and laundry. Proudly dubbed “the Queen of Auschwitz,” she regularly receives the spoils of her husband’s duties, from an expensive ermine fur coat to silky undergarments. When she gabs with friends, presumably the wives of other SS officers, they remark on the treasures they’ve found hidden in Jewish belongings. One woman chuckles over the diamond she discovered in toothpaste. Before Rudolf goes to work one day, Hedwig puts in her request: “Chocolate,” she says. “Any goodies if you see them.” Glazer, Jewish, shows that some of their motivations prove relatable: The Höss family wants what many people do: a nice place to call home, security for their family, and, every once in a while, an indulgence.

The Zone of Interest presents a near-constant negotiation between what we see and what we hear—and what we unavoidably imagine—going on just beyond the Höss property walls. Sound designer Johnnie Burn implants an ever-present whir that reverberates in the spectator’s body, reminding us that the unthinkable is occurring not far away. Drawing from the sounds of gunfire, barking guard dogs, the shouts of Nazis, and gut-wrenching screams from crowds of people, our minds paint a picture of the horrors playing out. Similar to this year’s Killers of the Flower Moon, Glazer’s film considers how people can compartmentalize something ghastly that they’re taking part in if it means their family benefits. In that film, Leonardo DiCaprio’s character participates in a murderous plot to exploit his Osage wife’s wealthy family, yet when he says he loves her, he means it. How does he reconcile these two seemingly conflicted positions, and does he even attempt to? One scene in Glazer’s film shows Rudolf enjoying an evening cigar, and upon noticing the light from the crematorium chimney, he turns his back—out of sight, out of mind.

The German-language film’s unthinkable juxtaposition of an orderly domestic space next to an extermination camp seems so monstrous that it almost defies reality, except Glazer relies on factual details. Rudolf Höss’ family actually lived near Auschwitz, within the so-called Interessengebiet (interest zone), just at the corner of the first camp. They “had it good” at the location, Rudolf wrote not long after his arrest in 1946, the year before a tribunal hung him for his crimes. Placing Rudolf at the center of a film might seem like a tasteless or hideous perspective to some. Why attempt to humanize Nazis? They’re monsters, after all, right? However, turning them into something almost supernatural does the reality of the Holocaust a disservice. The Zone of Interest remains exceptional among Holocaust films for looking directly at the limits of human behavior, viewing it not as an uncanny evil but as the twisted ways in which people can so fully immerse themselves within an ideology. Over time, people compartmentalize and rationalize their behavior to such extreme lengths that the appalling aspects no longer seem out of the ordinary. And it’s their ordinariness that remains shocking.

The German-language film’s unthinkable juxtaposition of an orderly domestic space next to an extermination camp seems so monstrous that it almost defies reality, except Glazer relies on factual details. Rudolf Höss’ family actually lived near Auschwitz, within the so-called Interessengebiet (interest zone), just at the corner of the first camp. They “had it good” at the location, Rudolf wrote not long after his arrest in 1946, the year before a tribunal hung him for his crimes. Placing Rudolf at the center of a film might seem like a tasteless or hideous perspective to some. Why attempt to humanize Nazis? They’re monsters, after all, right? However, turning them into something almost supernatural does the reality of the Holocaust a disservice. The Zone of Interest remains exceptional among Holocaust films for looking directly at the limits of human behavior, viewing it not as an uncanny evil but as the twisted ways in which people can so fully immerse themselves within an ideology. Over time, people compartmentalize and rationalize their behavior to such extreme lengths that the appalling aspects no longer seem out of the ordinary. And it’s their ordinariness that remains shocking.

Besides the inherent divergence between what we see and what we hear, the narrative conflict emerges when Rudolf is to be transferred to the German town of Oranienburg, the site of one of the earliest concentration camps. At this news, Hedwig feels affronted. “You can’t do this to me,” she says, thinking of the home she has built next to Auschwitz—where trains routinely deliver new stores of Jews, where the blue sky is blotched by the putrid green smoke of human ash, where the bedrooms glow orange at night from the furnace fires in the distance. Though her mother visits and observes that Hedwig has “landed on her feet,” she leaves in the night without a word, having been horrified by that glow. Regardless, Hedwig argues that the house is “Everything we want,” and she refuses to leave. Rudolf will go without her and the family, and they will reconnect after the war. However, saying goodbye to his favorite horse is more difficult than parting from Hedwig. And so, Rudolf screws the Jewish girl he’s been consorting with one last time, after which he compulsively washes his genitals, and then he’s off to his new promotion. It’s all so maddeningly routine.

Glazer and Polish cinematographer Łukasz Żal craft an observant style that regards this household with objective distance. The shots, almost entirely medium and wide compositions, often employ a one-point perspective view down hallways or move tableau-style in parallel with walls. Editor Paul Watts’ cutting is logical, following the action with a shot-to-shot logic that creates a clear understanding of the spatial geography. The rigid visual treatment contrasts Levi’s mesmeric score, a winding piece of music that turns every image into a disturbing evocation. Disruptions to the film’s rigorous visual agenda do occur, such as a montage of flowers from Hedwig’s garden that rings with sounds of violence nearby. Elsewhere, Glazer includes sequences that might be nightmares, passages from a fairy tale such as Hansel and Gretel, or simply a look at another world—one so different from the Höss’ that it registers as an anti-world. Rendered using thermal imagery that looks like a photo negative, these sequences follow a Polish girl who scampers in the night, collects and redistributes fruit, and evades Nazi guards. They’re as abstract and expressionist as the wildest moments from Glazer’s body of work.

Glazer’s 20-year career as a feature filmmaker echoes those of Stanley Kubrick or Terrence Malick in their spare periods. Apart from music videos and short films, he has only made four feature films, including his latest, and each is a masterwork. Moreover, his aesthetic has changed dramatically since his terrific 2001 debut, Sexy Beast, a popish British crime yarn with a touch of the surreal. With the controversial Birth (2004), which finds Nicole Kidman weighing whether or not her late husband has been reincarnated into a teenage boy, followed by the sublime sci-fi tale Under the Skin, Glazer’s style has become ever more austere and experimental. He has spent the last decade developing The Zone of Interest, grappling with the subject matter and how to approach it. But as cultures around the world have become ever more radicalized, openly racist, and reflective of—if not fully embracing—the Nazi ideology, The Zone of Interest seems like less of a historical portrait than a mirror. The film serves as a reminder that the Holocaust wasn’t the product of abstract creatures; it was everyday people, not dissimilar from your friends and neighbors, who sought to exterminate Jews through an ever-more efficient system.

Glazer’s 20-year career as a feature filmmaker echoes those of Stanley Kubrick or Terrence Malick in their spare periods. Apart from music videos and short films, he has only made four feature films, including his latest, and each is a masterwork. Moreover, his aesthetic has changed dramatically since his terrific 2001 debut, Sexy Beast, a popish British crime yarn with a touch of the surreal. With the controversial Birth (2004), which finds Nicole Kidman weighing whether or not her late husband has been reincarnated into a teenage boy, followed by the sublime sci-fi tale Under the Skin, Glazer’s style has become ever more austere and experimental. He has spent the last decade developing The Zone of Interest, grappling with the subject matter and how to approach it. But as cultures around the world have become ever more radicalized, openly racist, and reflective of—if not fully embracing—the Nazi ideology, The Zone of Interest seems like less of a historical portrait than a mirror. The film serves as a reminder that the Holocaust wasn’t the product of abstract creatures; it was everyday people, not dissimilar from your friends and neighbors, who sought to exterminate Jews through an ever-more efficient system.

The Zone of Interest seeks to demystify what professor and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel called “the ultimate mystery.” Though Glazer characterizes humanity’s selfish and disturbing mode of cruel indifference in scene after scene, and much of the film could exist on a loop in a modern art installation, he’s not merely making the same point over and over. The humdrum lives of the Höss family add a human dimension to the offenders in a way few films have, making a bold statement about the very real depths to which people can sink. The film posits that, while unique in its sweep and lasting wounds, the Holocaust is not monstrosity but humanity at its worst, purveying genocide, of which history has had many; though, the regularity of genocide around the world should not in any way diminish the Holocaust’s horrors. With its modern-day coda of the custodial staff in the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum mindlessly polishing floors and wiping windows, unmoved by the vast cases of belongings gathered from those who the Nazis murdered, The Zone of Interest remarks on how people find it easier to process human barbarity in containers. Whether they are literal glass cases, warped rationalizations, or othering, humanity’s capacity for dehumanization is disturbingly present.

Consider Supporting Deep Focus Review

I hope you’re enjoying the independent film criticism on Deep Focus Review. Whether you’re a regular reader or just occasionally stop by, please consider supporting Deep Focus Review on Patreon or making a donation. Since 2007, my critical analysis and in-depth reviews have been free from outside influence. Becoming a Patron gives you access to exclusive reviews and essays before anyone else, and you’ll also be a member of a vibrant community of movie lovers. Plus, your contributions help me maintain the site, access research materials, and ensure Deep Focus Review keeps going strong.

If you enjoy my work, please consider joining me on Patreon or showing your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review