The Zero Theorem

By Brian Eggert |

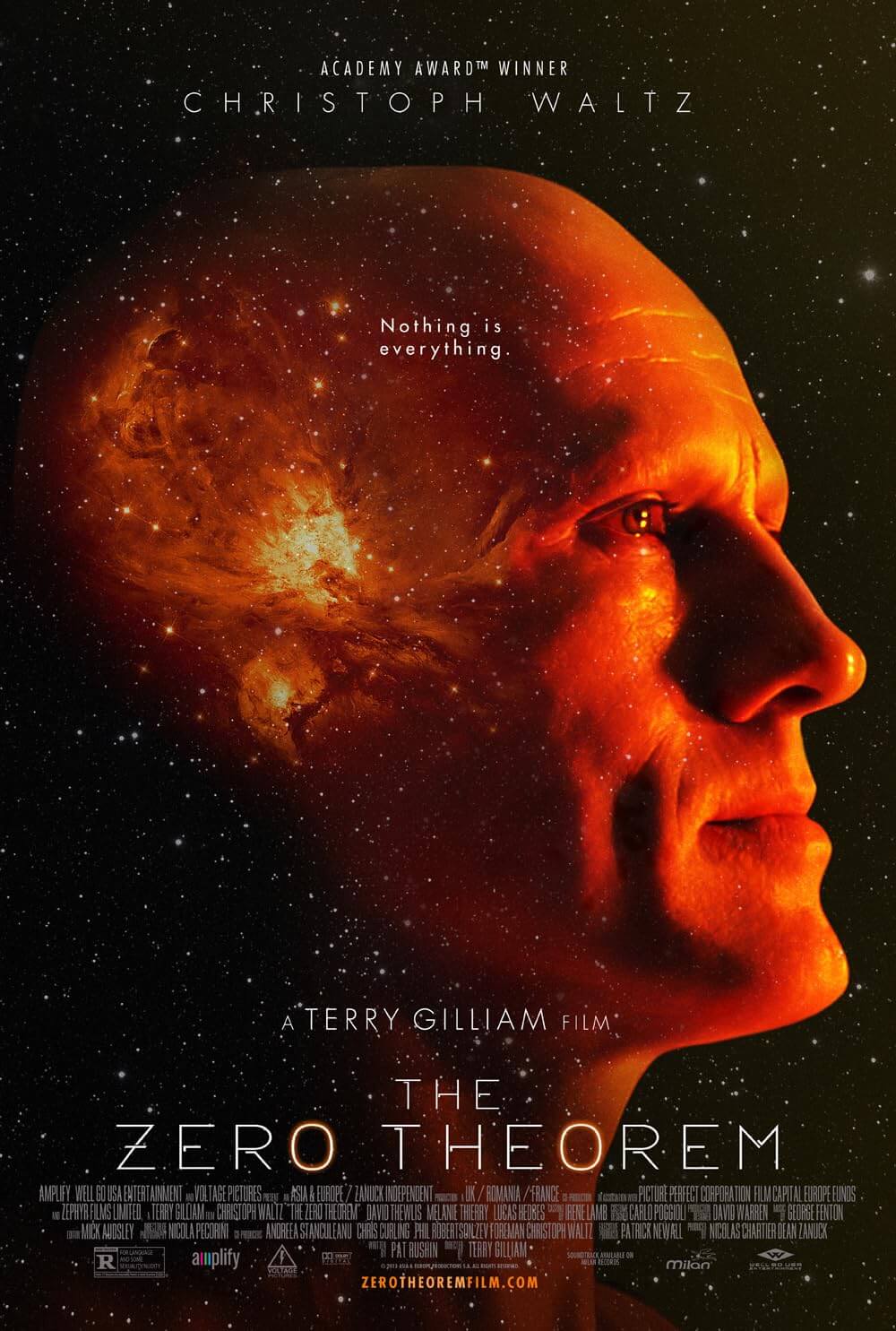

Terry Gilliam’s The Zero Theorem takes place in a world that looks like a potential future, conceivably where we’re headed in about twenty years. Huge skyscrapers and blimps look down from above on bustling, graffiti-lined city streets where minicars buzz along without slowing for pedestrian traffic. On the sidewalks, plastic florescent clothing styles pop with bright patterns and see-through coverings, and wispy gel hairstyles resemble Katsushika Hokusai’s ocean waves. Huge video billboards for “The Church of Batman the Redeemer” blare overhead, while a personalized ad for financial services streams alongside people as they walk. Workplaces segment employees into frantic little cubicles where they punch away on controllers and operate a videogame-like process with no discernable objective. At night, parties rage on under animal costumes and bouncy dancing to loud electronic music, everyone tuned in and isolated on their glowing tablets and smartphones. Sexual intercourse takes place online through wires in a convincing cyber reality to avoid any threat of disease. And though this oppressive world seems years ahead of where we are now, if you asked Gilliam, he’d probably say his film is set in the present day.

In 1985, Gilliam released Brazil and presented a modern world of Orwellian surreality to reflect our own twentieth century, wherein a lowly office drone escapes the stifling congestion around him by dreaming himself into a heroic open-air fantasy. Just as complex visually as The Zero Theorem, that film benefited from a narrative thrust about its hero, Jonathan Pryce’s distracted Sam Lowry, finding the physical embodiment of his actual dream girl. Gilliam’s latest feels closely related to Brazil, though its narrative is more nebulous. It was based on an original screenplay by UCF English professor Pat Rushin, who must have had Gilliam’s Brazil in mind when he was writing. Both films involve a company drudge who toils away but becomes sidetracked by a woman, and while he grows ever-closer to the answers he’s seeking, he comes dangerously close to losing his grip on reality. The search for meaning amid a repressive world of big business and computerization drives every facet of these films. Consider them variations on a very Gilliam theme and more closely related than any other two of the director’s films.

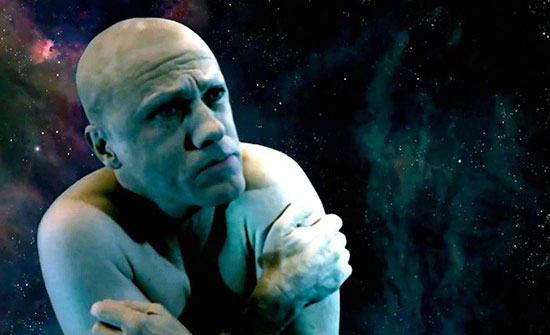

Christoph Waltz plays Qohen Leth, the top-performing number-cruncher for Mancom, the omnipresent company of the picture. Hairless, cracked, and put upon by the busied world around him, Qohen refers to himself as “we”. He seeks solitude and answers. At Mancom, he begs his supervisor (David Thewlis), who endlessly calls him “Quinn”, to work from home where he’ll be more productive, and where he can wait for a call he’s expecting—a call that he’s convinced will explain to him the meaning of existence. To work from home, Qohen must convince Management (Matt Damon, sporting a blond wig and animal print suits that camouflage him in his surroundings) that he’ll be more productive. And when he’s finally granted the opportunity, he’s assigned a special project to find the Zero Theorem, a mathematical equation that will prove “Everything is nothing” and, therefore, there is no purpose to the universe. Proving the Zero Theorem would seem to confirm all of Qohen’s worst fears, and yet he toils incessantly to prove it, destroying his own beliefs as he continues to make progress.

Inside the ramshackle skeletal remains of the church that he calls his home, the faithful Qohen sleeps on the pipe organ and has nightmares of a spatial black hole sucking everything into its nothingness. Behind his large-screen workstation, the Jesus head on a crucifix has been replaced by a camera through which Management watches Qohen’s progress, charted on a video program where blocks assemble a mathematical equation in which “0 must equal 100%.” Always a few percentage points off, Qohen’s harried efforts are ill-relieved by Dr. Shrink-Rom (Tilda Swinton, a shade more outlandish than her turn in Snowpiercer), his virtual psychiatrist program. Perhaps as a healthy diversion, or perhaps as an intended interruption, Management sends Qohen the irresistible Bainsley (Mélanie Thierry), a flirtatious disruption to whom Qohen slowly warms up, and perhaps even falls in love with, but ultimately disregards. Also there to stabilize or dismantle Qohen’s progress is Management’s own 15-year-old son, Bob (Lucas Hedges), who takes sympathy on the menial laborer, knowing the impossibility of the task Qohen’s been given.

Inside the ramshackle skeletal remains of the church that he calls his home, the faithful Qohen sleeps on the pipe organ and has nightmares of a spatial black hole sucking everything into its nothingness. Behind his large-screen workstation, the Jesus head on a crucifix has been replaced by a camera through which Management watches Qohen’s progress, charted on a video program where blocks assemble a mathematical equation in which “0 must equal 100%.” Always a few percentage points off, Qohen’s harried efforts are ill-relieved by Dr. Shrink-Rom (Tilda Swinton, a shade more outlandish than her turn in Snowpiercer), his virtual psychiatrist program. Perhaps as a healthy diversion, or perhaps as an intended interruption, Management sends Qohen the irresistible Bainsley (Mélanie Thierry), a flirtatious disruption to whom Qohen slowly warms up, and perhaps even falls in love with, but ultimately disregards. Also there to stabilize or dismantle Qohen’s progress is Management’s own 15-year-old son, Bob (Lucas Hedges), who takes sympathy on the menial laborer, knowing the impossibility of the task Qohen’s been given.

Rushin had written the script more than a decade ago, and at various stages, producers Richard D. Zanuck and his son Dean had stars from Ewan McGregor to Billy Bob Thornton to Al Pacino set to star. Gilliam had signed on and signed off again during his troubles on The Imaginarium of Dr. Parnassus (2009). But eventually, the international co-production was underway with two-time Oscar winner Waltz starring and shot in Romania on an amazingly short 36-day schedule—amazing because of the level of detail that Gilliam and production designer David Warren (Sunshine, Hugo) inject into the film. Every frame pops with the Monty Python cartoonist’s graphic eye, the backgrounds busy with colors and images, ironic and satirical. Visual gags from a musical pizza box, to the mice living in the walls in Qohen’s church, to the kaleidoscopic dot-sex stripper-cam website run by Bainsley are alive with Gilliam’s unique touch. Taking everything in over one viewing would almost certainly be impossible, as is the case with any Gilliam film. And like such cluttered, chaotic Gilliam worlds as The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988) and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1998), The Zero Theorem will only get better, funnier, and more insightful with repeated viewings.

Despite comic flourishes, it would be wrong for viewers to look upon The Zero Theorem as anything but a tragedy, as hinted by George Fenton’s melancholic score. Rushin was inspired by segments of the Hebrew bible’s book of Ecclesiastes, which, in an interview, he says asks questions like “What is the value of life? What is the meaning of existence? What’s the use?” Qohen’s name was taken from the book’s Hebrew title, “Qoheleth”, which means gatherer or teacher. And what, through the course of the film, does Qohen teach us? Some critics have remained baffled by Gilliam’s purpose, saying the film “doesn’t add up to much”. But there’s a prevailing message that the search for meaning itself becomes a distraction that only leads to the abyss of solitude, loneliness, and confusion. Whereas the important things in life, such as friends and love, represented through Bob and Bainsley respectively, carry on and, when not embraced, become sources of regret later in life. By the heartbreaking last shots of The Zero Theorem, we cannot help but realize that the fateful phone call, or the oh-so-close equations on which Qohen toiled for answers, were ultimately meaningless and served only to distance him from what would bring him true happiness.

Interpretations of The Zero Theorem may vary, but for this critic, Gilliam and Rushin argue that the universe is a cold and empty place, waiting to be filled with our own sense of purpose. They approach this world with an evident cynicism about the absurdity and pointlessness of our modern way of living, but it’s relayed through humor and Gilliam’s brand of unhinged surrealism that has pervaded his output from Time Bandits (1981) to The Imaginarium of Dr. Parnassus and everything in-between. In a world inundated by stimuli, how can anyone know what they desire, or hope to achieve any kind of meaningful realization about themselves? Some audiences may not have the patience or faculty to sift through Gilliam’s visual deluge to find those answers; stimulation overload is bound to occur. But then, isn’t that the point of Gilliam’s form-follows-function approach, to push aside the unnecessary distractions and assign the bleak universe, or neverending neural nets that might be a universe unto themselves, a significance all your own? Any meaning outside of what we create for ourselves is nonexistent, and so nothing is everything. It’s a powerful message under Gilliam’s demanding, over-stimulated surface spectacle, but sorting through the experience has a profound reward.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review