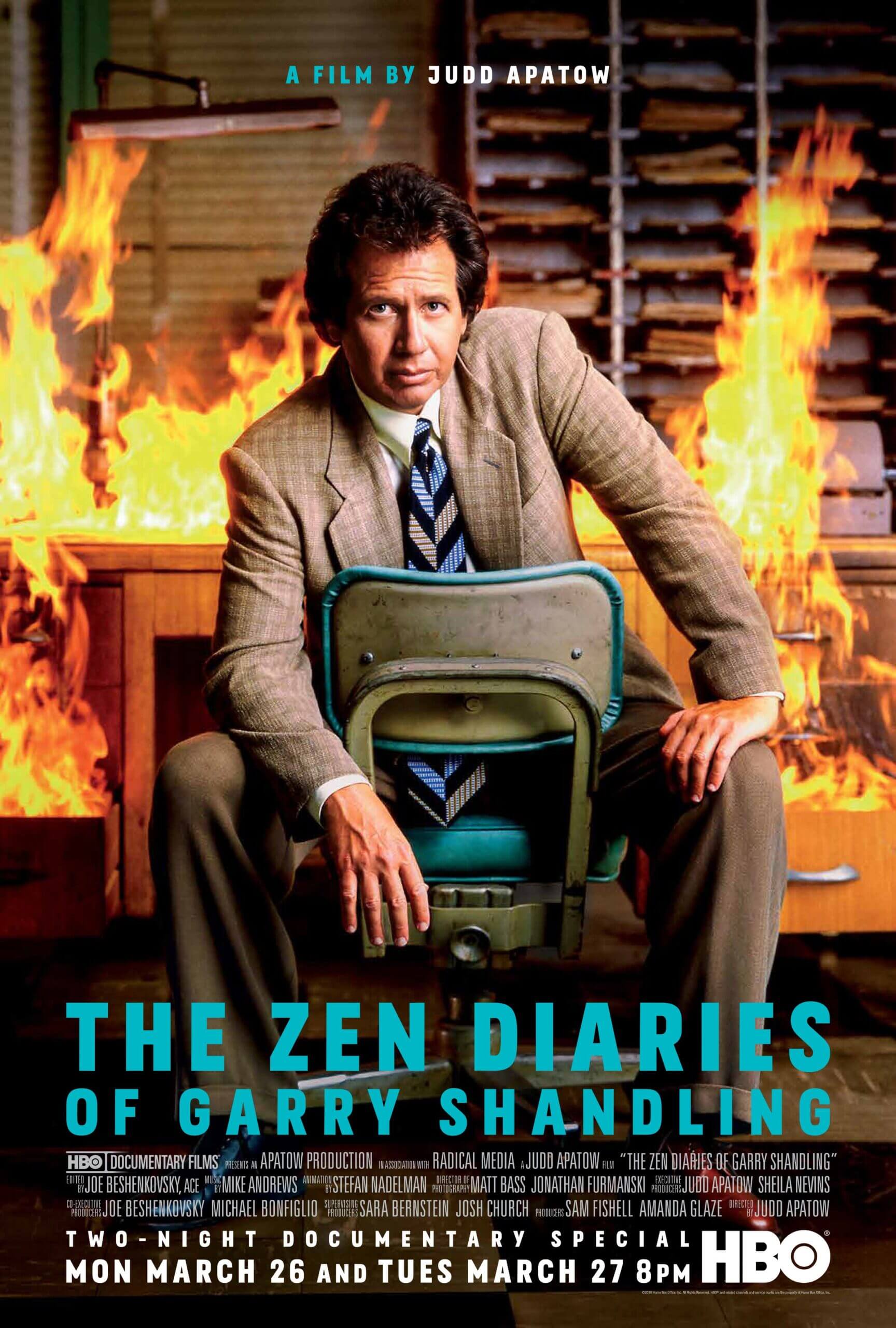

The Zen Diaries of Garry Shandling

By Brian Eggert |

Watching the HBO documentary The Zen Diaries of Garry Shandling, I felt as though director Judd Apatow had introduced me to a great friend and, by the end, I had lost him. Oddly, I grew up watching Garry Shandling on television, though I was much too young to understand his self-deprecating humor, sexual commentary, and Freudian schtick about his Jewish mother’s obsession with him. But he was a different television presence than the average comedian or star, and even as a young child I understood that. On Showtime’s It’s Garry Shandling’s Show (1986-1990), he pioneered a new strain of meta-humor—long before meta had become an all-too-common descriptor—through his character’s awareness that he was on a situation comedy. Breaking the fourth wall, Shandling looked out at his viewers, and I connected with him, and that show, more than other comedians or shows. He made me feel as if I was in on the joke, since he was the only television star talking to me. Over the years, perhaps because of this, and because he continued to be hilarious the more I watched his work, I have maintained a fondness for Shandling. And when he died of a heart attack in 2016 at the age of 66, it felt like a loss. All of this is just to confess that, while The Zen Diaries of Garry Shandling is a well-made film, its impact may have been more personally significant for me than the average viewer, which undoubtedly has shaped my love of this documentary.

Apatow, who worked with Shandling closely over the years as a mentee, notably as a writer and director on HBO’s The Larry Sanders Show (1992-1998)—easily one of the smartest, funniest shows ever televised—has often been accused of making overlong comedies. Both Funny People (2009) and This is 40 (2012) have around two-hour-and-fifteen-minute runtimes, and the viewer feels the length in each case. Yet, every moment of his four-and-a-half-hour documentary about Shandling (broken into two parts by HBO) feels essential. I never checked the clock, and I completed both parts in one sitting. Apatow has lovingly sought to get at the sources of Shandling’s humor, ego, vulnerability, neuroses, and surprisingly, his lifelong search for inner peace through meditation. He interviews Shandling’s friends and colleagues, uses home video from Shandling’s childhood, and offers archival clips of his stand-up and television appearances. But above all, Apatow uses Shandling’s inventory of diaries, which he had kept since his late teens. In one of the many clips from Apatow’s own behind-the-scenes videos of Shandling, the comedian looks over one of the diaries and observes, “Here I’m on my way to Hawaii, and I say I like the weather.” He takes a moment and smiles in that dry, pained Shandling way. “So, you know, they’re filled with that kind of depth you can’t get anywhere else… But here’s what you get: My entire fucking life.”

Shandling was born in Chicago in 1949, but his parents moved the family to the warmer, drier climate of Tuscon shortly after discovering their elder son, Barry, was suffering from cystic fibrosis. The two brothers were inseparable, and so Barry’s death when Shandling was just ten became a formative moment for the performer’s life, and for Apatow’s doc. Shandling’s uncommunicative parents refused to let their remaining son attend the funeral; he didn’t even know his brother was gone until after the service. Shandling’s diary reads, “as mom put it, ‘I didn’t want you to see me crying.'” He continues, “I had no one (that I recall) putting a hand on my should or saying, ‘this is death, this is sadness, this is grief. Stay with the pain and let’s walk through it.'” After Barry’s death, Shandling’s mother, Muriel, smothered him to compensate for the loss. This lasted for the rest of his life and informed his material. “My mother wanted me to have kids, but not with another woman,” he said in his act. Shandling’s ongoing feeling of betrayal by his parents and aloneness after the loss of his brother remained with him, and in response, he explored meditation and Zen Buddhism to center himself.

Shandling was born in Chicago in 1949, but his parents moved the family to the warmer, drier climate of Tuscon shortly after discovering their elder son, Barry, was suffering from cystic fibrosis. The two brothers were inseparable, and so Barry’s death when Shandling was just ten became a formative moment for the performer’s life, and for Apatow’s doc. Shandling’s uncommunicative parents refused to let their remaining son attend the funeral; he didn’t even know his brother was gone until after the service. Shandling’s diary reads, “as mom put it, ‘I didn’t want you to see me crying.'” He continues, “I had no one (that I recall) putting a hand on my should or saying, ‘this is death, this is sadness, this is grief. Stay with the pain and let’s walk through it.'” After Barry’s death, Shandling’s mother, Muriel, smothered him to compensate for the loss. This lasted for the rest of his life and informed his material. “My mother wanted me to have kids, but not with another woman,” he said in his act. Shandling’s ongoing feeling of betrayal by his parents and aloneness after the loss of his brother remained with him, and in response, he explored meditation and Zen Buddhism to center himself.

Though he excelled at engineering and science in college, Shandling resolved to focus his hard work ethic into a lifelong interest: comedy. Taking a fateful chance, he drove to Phoenix to catch George Carlin performing at a comedy club and delivered several pages of material he’d written for him. Carlin could have tossed the 19-year-old Shandling’s material, but instead, he left a note saying that every page contained something funny, and to keep at it. Carlin’s example would become a model for Shandling later in life when he mentored young comedians like Sarah Silverman and Kevin Nealon. Before long, Shandling moved to Los Angeles and secured a job writing scripts for shows like Sanford and Son and Welcome Back, Kotter. He soon realized that he wanted to perform standup. He gradually developed a craft, taking dance lessons to improve his stage presence and posture, perfecting every punchline of his material. He told jokes about himself, his insecurities, his self-obsession, and his sexual humiliation. One of his greatest lines, “My girlfriend moved in with another guy, so I dumped her, because that’s where I draw the line” speaks to his way of making his foibles funny, while his delivery somehow evokes confidence. “Nothing ever felt so right,” he wrote about performing.

Shandling’s commitment to honing his naturalism and distinct on-stage persona comes through in his diary entries, which show his growing interest in Buddhism and finding happiness. He seems divided between his desire for success and acceptance and his desire for happiness. Messages to himself such as “Just be Garry” and “Commit to killing” speak to the former, while later he writes, “I don’t even want to be a great comedian anymore. I just want to have fun and be happy.” For instance, after finally achieving his dream with a seminal standup appearance on The Tonight Show, he later had the opportunity to take over for Johnny Carson. By this time, It’s Garry Shandling’s Show was a creative and critical hit, and the freedom and control he had over his own show convinced him to pass on what would’ve become a repetitive task of doing The Tonight Show. As Apatow intimates, Shandling labored over his comedy and avoided making decisions until the last possible moment. He liked to retool his jokes and find the perfect punchline, which many of the interviewees in the doc attest he could do in no time at all. In overseeing (and perhaps overthinking) every detail of his television appearances, he could protect his fragile ego by delivering the best jokes. As a late-night host, however, one is expected to have a bad night here and there. Shandling refused to have bad nights.

Perhaps that’s why he created The Larry Sanders Show, his landmark satire about the behind-the-scenes hullabaloo of a late-night talk show, as it was the best of both worlds: a talk show whose script he could control, ensuring it would never become repetitive. On the surface, the show was about the inflated egos of everyone in the entertainment industry, especially Larry Sanders, who seemed like an autobiographical character for Shandling. “Some people mistakenly think that’s a dark show about people trying to get what they want,” Shandling once said. “No, it’s a show about people trying to get love and that shit gets in the way.” But the show’s star grew exhausted by the creative effort, which was rewarded with a number of dramatic off-screen scandals that, in time, found their way into the show’s storylines. Apatow’s doc observes that art imitated life in the series, but eventually, life imitated art.

Perhaps that’s why he created The Larry Sanders Show, his landmark satire about the behind-the-scenes hullabaloo of a late-night talk show, as it was the best of both worlds: a talk show whose script he could control, ensuring it would never become repetitive. On the surface, the show was about the inflated egos of everyone in the entertainment industry, especially Larry Sanders, who seemed like an autobiographical character for Shandling. “Some people mistakenly think that’s a dark show about people trying to get what they want,” Shandling once said. “No, it’s a show about people trying to get love and that shit gets in the way.” But the show’s star grew exhausted by the creative effort, which was rewarded with a number of dramatic off-screen scandals that, in time, found their way into the show’s storylines. Apatow’s doc observes that art imitated life in the series, but eventually, life imitated art.

Indeed, Apatow’s affectionate portrayal of Shandling does not avoid his downfalls, such as a particularly ugly situation when, after breaking up with longtime girlfriend Linda Doucett, he fired her from The Larry Sanders Show, and she responded with a winning wrongful termination suit. Another lawsuit, this one filed by Shandling against his former manager, Brad Grey (who, upon his 2017 death, was chairman and CEO of Paramount Pictures), sought $100 million from Grey because he betrayed Shandling and used his status as a Larry Sanders producer to broker self-serving deals. While both of these lawsuits reveal how petty Shandling could be, they also suggest how wounded he was—a lingering quality since the loss of Barry, his parents’ reaction, and the feeling that he could no longer expose himself to the potential loss of deep human relationships. Doucett, in tears, recalls that her breakup with Shandling was because she wanted children, but Shandling could not bear the possibility of bringing a child into the world and losing it, like he lost Barry.

During the film’s second half, Apatow explores Shandling’s life after The Larry Sanders Show, and how disenchanted he had become with the entertainment industry following Grey’s dishonesty. While his career waned with a few uninspired movie projects (among them Town and Country (2001), one of the biggest flops in film history), he took pride in hosting the Emmys, his voicework (and rewriting of) his role as a turtle in Over the Hedge (2006), and conceiving particularly creative special features for the DVD boxed set of The Larry Sanders Show. He started to spar regularly at a private boxing gym he co-owned with Peter Berg. But chiefly, after surviving pancreatitis and having his thyroid removed, he mentored younger talent including Conan O’Brien and Sacha Baron Cohen, occasionally performed standup, and found himself. Shandling became more invested in Buddhism and meditation all the time, he learned forgiveness and began to set aside his desire for success. “Garry wasn’t interested in Zen because he was Zen,” noted Silverman. “He was interested in Zen because he needed Zen.” When he died, it seemed as though he died happy.

Apatow assembles a warm and honest portrait of Garry Shandling, one that will give his fans a chance to understand him and others a chance to appreciate him. As one might expect, The Zen Diaries of Garry Shandling features an exhaustive list of celebrities and comics with stories about their friend and mentor. Apatow cuts between them, Shandling’s stage performances, and handwritten segments of the diaries with a cohesiveness that keeps the film moving. The form never becomes monotonous. There’s a sense of discovery, as though we’ve plunged into someone’s life story with intimate candor, openness, and sensitivity. Shandling’s personality and work ethic emerge throughout the extensive film. Apatow depicts him as a complicated and perhaps tortured performer whose devotion to creating comic art was second only to his desire for happiness. For those unfamiliar or uninterested in Shandling’s life and career, a more than four hour documentary about Garry Shandling may not work for you. But Apatow tells a human story full of laughter and tears, achieving profound moments that evoke the essence of his subject to the audience. And while a certain preexisting affinity certainly helps engage, the film introduces us to the human being and artist Garry Shandling, allows us to appreciate his talent and vulnerability, and leaves us mourning his loss. “Stay with the pain and let’s walk through it,” Apatow’s doc seems to say, giving his audience the catharsis Garry sought his entire life.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review