The Young Victoria

By Brian Eggert |

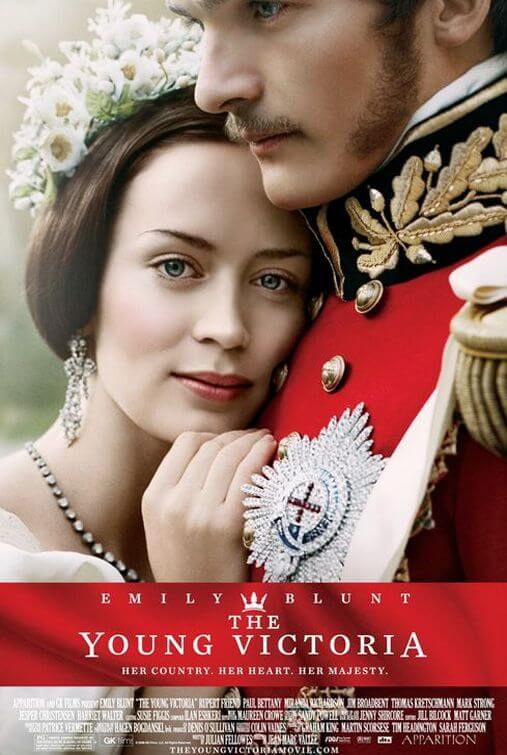

The Young Victoria covers a timeframe from 1836 to 1841, a brief but important section in the life of its subject, Queen Victoria. The plot drifts back and forth between romance and some minor political intrigue of the era; don’t expect the romance to get too juicy or the politics to become too bloody, though, as the PG rating wouldn’t allow it. The problem is, the film never knows on which story it should settle, as it’s too busy being a by-the-numbers period piece. Aimless though it may be, the film’s director Jean-Marc Vallée shoots the costumes and the architecture with a sharp eye, even if the characters filling them don’t always keep our attention.

Beginning a year before Victoria (Emily Blunt) is crowned, the film opens with her mother, the Duchess of Kent (Miranda Richardson), and the household’s top adviser, Sir John Conroy (Mark Strong), plotting to make Victoria sign papers that would make them regents—the powers behind the throne. The death of King William (Jim Broadbent) approaches, and they must act fast if they intend to wield the young sovereign’s future power. But Victoria refuses to sign and she’s crowned Queen, though she’s placed into a position that’s overwhelming to her youth and inexperience. But then, her mother intended Victoria to be naïve so that she might be too frightened to take the throne. As it is, Victoria plays a dangerous game of politics with players that are much better than she. Such a player is Lord Melbourne (Paul Bettany), the Prime Minister, who intends to woo her and use her authority by gaining her trust. Melbourne becomes Victoria’s top adviser, and his control over her grows so that England begins to suspect her favoritism of his political views, thus harming her reputation as a fair Queen.

Through all of this, Victoria meets and exchanges letters with Prince Albert (Rupert Friend) of Belgium. Albert’s father, King Leopold (Thomas Kretschmann), who is also Victoria’s Uncle, wants desperately to secure his son’s marriage to the Queen. As the letters between Victoria and Albert continue, so does her receptiveness to Melbourne’s political suggestions. Only through her eventual marriage to Albert does she finally become the responsible and favored monarch that history remembers. The romance between Victoria and Albert would seem to be the chief selling point of this story, but they’re a rather dull couple. They play chess and ride horses together, but mostly we understand their relationship through the device of their letters. And because the letters are opened and read by their advisors for any hints at political dealings, the writers must keep their words extraordinarily proper, which doesn’t help the audience to learn much about the film’s only emotionally resonant characters.

That’s not to say that the other characters aren’t interesting, they’re just not that well-developed. Bettany’s performance as the slick and smart adviser makes one completely forget that he was in Legion, which is saying something. Broadbent’s brief role as King William offers more range than the entire remainder of the cast. Richardson flip-flops wonderfully between a conniving parent to a remorseful mother. And Mark Strong proves once again that he’s today’s best-supporting actor, even if he had a better chance of taking over the British government in Sherlock Holmes than he ever did here. Each of these small roles is played to perfection by the secondary cast members, and they give more reason to see the film than the leads.

Blunt’s portrayal of Victoria doesn’t inspire admiration, either in the performance or in the character. She’s serviceable, but she doesn’t draw the audience to her, which then leaves us at a distance from the film. For a more memorable performance and a more stirring persona, one should look no further than Judi Dench’s representation of Queen Victoria in Mrs. Brown. Blunt’s sleepy eyes and plain-Jane presence feel understated in comparison. But maybe the actress isn’t to blame. Perhaps it’s the fault of screenwriter Julian Fellowes, who chose such a dull period in Victoria’s life to write about. There’s little to follow with much interest besides the reading of letters between Victoria and Albert via narration. If audiences wanted that, they could see the latest Nicholas Sparks adaptation.

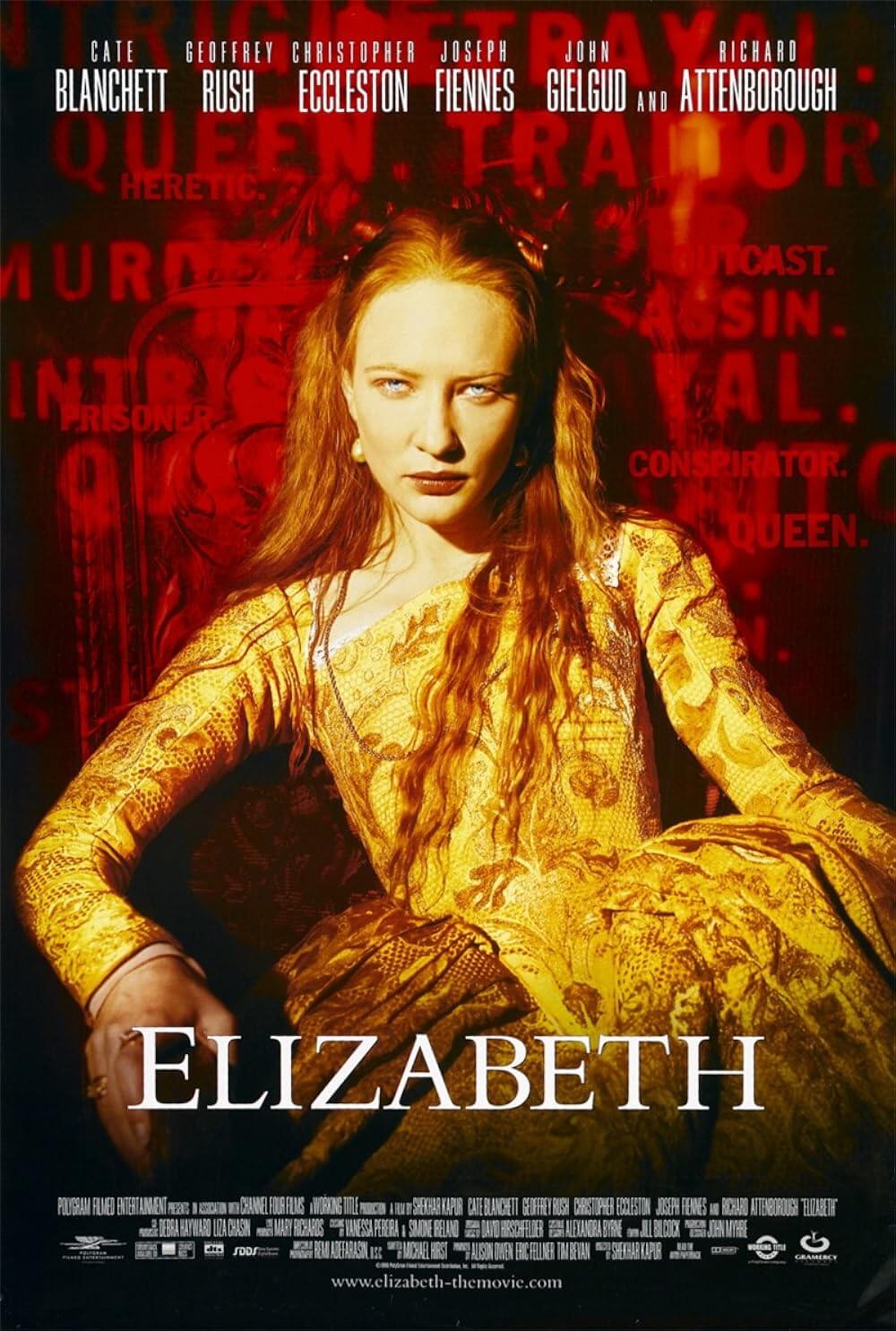

In a way, The Young Victoria recalls Elizabeth: The Golden Age, another period film that chose to only vaguely dwell on the most interesting aspects of the story. Still, it’s understandable why the film earned Oscar nominations for Art Direction and Costume Design. This is a beautiful production to behold, even if there isn’t much going on in the foreground to make the scenery truly come alive. Moviegoers will lose themselves in the elaborate costumes and the period rhetoric, but for some, that won’t be enough. For fans of this sort of film, there’s much to relish, yet it’s doubtful audiences will find any meaningful connection to this otherwise empty, forgettable experience.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review