The World to Come

By Brian Eggert |

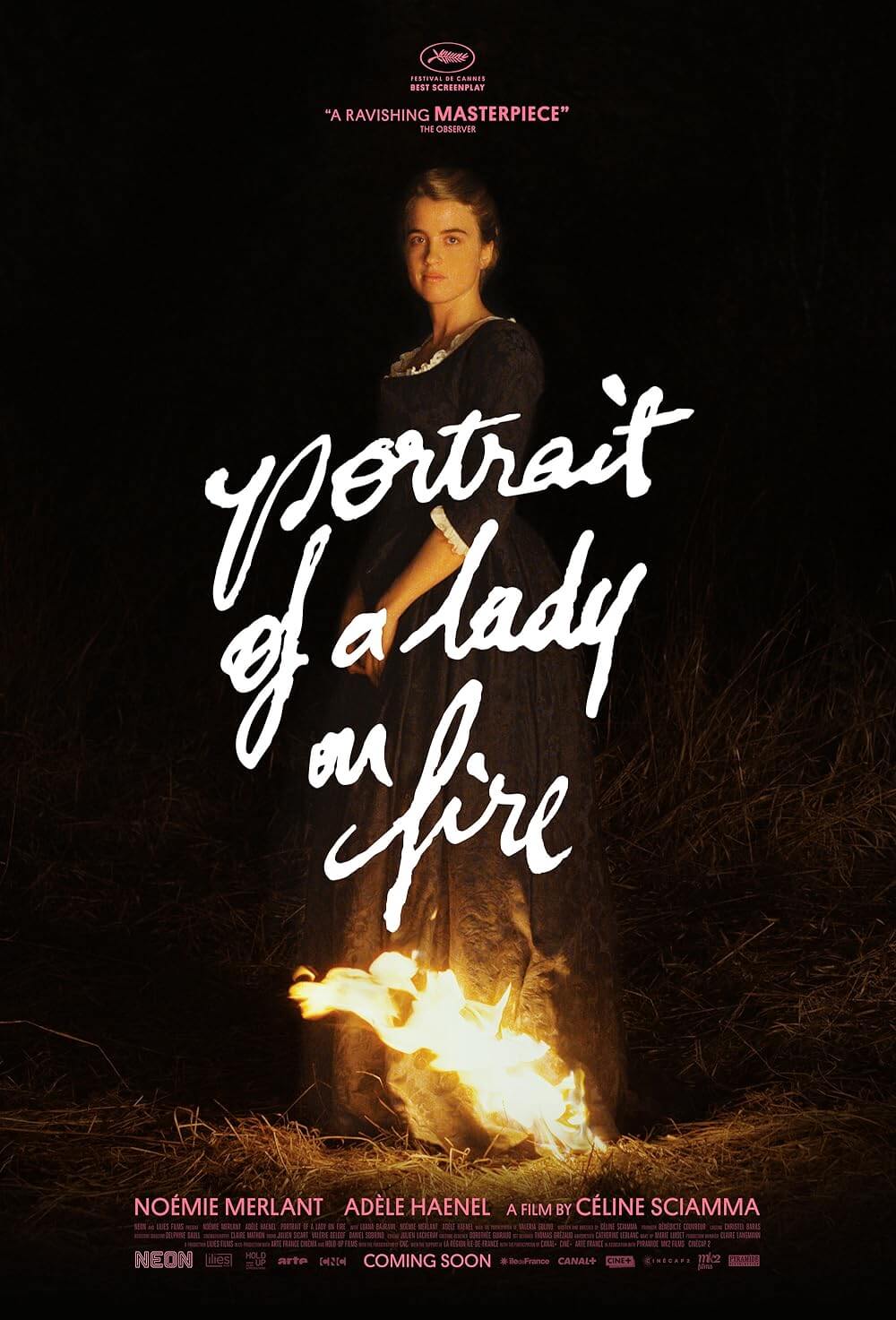

In the realm of LGBTQ+ romances set in a distinct place and time, recent examples from Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019) to Francis Lee’s Ammonite (2020) fare better than Mona Fastvold’s The World to Come. In these films and others, including Todd Haynes’ Carol (2015), women’s requisite interiority in patriarchal societies, particularly queer women, becomes a wellspring for repressed emotions and doomed romances. It’s inherently dramatic material often accompanied by formal choices that both reflect the crushing cultural oppression and reticence experienced by their characters. Dour and drained of vivid colors, Fastvold’s film takes place in the journals of Abigail (Katherine Waterston), an unhappily married woman grieving the loss of her daughter to diphtheria a few months earlier. She confines her expressions to journal entries, which she reads aloud in the film’s voiceover. The first entry on January 1 reflects her luminous internal life circumscribed by loss and a loveless companionship: “This morning, ice in our bedroom for the first time all winter,” she acknowledges in one of her many weather reports that doubles as a description of her life’s passion or lack thereof. “With little pride, and less hope, we begin the new year.”

Set in upstate New York in 1856, the film occupies Abigail’s melancholic outlook, reflected by cinematographer Andre Chemetoff’s grayish winter color palette and narrow aspect ratio (1.66:1). She receives a beacon of hope with the arrival of new neighbors. The possessive pig farmer Finney (Christopher Abbott) is accompanied by his wife Tallie (Vanessa Kirby), whose voluminous red hair and blue eyes catch Abigail’s attention. Our heroines begin with a polite friendship after Tallie conducts an initial neighborly visit, but soon she becomes the only source of the otherwise stone-faced Abigail’s joy—a detail that does not go unnoticed by her husband, Dyer (Casey Affleck). “My reluctance seems to have become his shame,” Abigail admits of Dyer’s remoteness. But before the inevitable romance, our only sense of Abigail’s true feelings for Tallie comes out in the voiceover of journal entries. They have an untrained yet intense poetic style that, while open-hearted and occasionally lofty in the contemporary style, conveys her delight and confusion about her growing affections for Tallie. Her poetic sentiments are almost comically contrasted by her frank descriptions of “an enema of molasses, warm water, and lard” given to Dyer to treat a fever. “Also a drop of turpentine next to his nose” to clear congestion.

Based on Jim Shepard’s book, Shepard and Ron Hansen’s adaptation resembles a contingent of quiet, understated period pieces in which talented performers must restrain themselves from overstating their characters’ unspoken desires and dissatisfaction with their lives. The story unfolds on the countryside, where some women are beaten for not adhering to their “wifely duties,” while some wives are poisoned by disapproving husbands. Dyer isn’t so stern as Finney, who quotes the Bible and demands obedience with violence. Rather, Dyer seems preoccupied with maintaining the farm, his focus as machine-like as his daily ledgers and hand-cranked apple peeler. Affleck’s role carries surprising weight, and the viewer’s empathy for Abigail begins to compete with Dyer, a likewise broken and decent person. After all, he’s no Finney. He doesn’t beat his wife or demand explanations; he’s too grief-stricken and solitary for that. And his wife’s increasing disinterest in his workmanlike presence begins to resemble a tragedy for Dyer that goes somewhat overlooked by Fastvold. Of course, Dyer’s inner life isn’t the point of The World to Come, but Abigail’s treatment of him seems callous at times. Neither of them knows how to love one another, which becomes evident in every interaction. It’s just bad luck that Abigail found someone else.

Fastvold’s approach is perhaps too eager to articulate what the characters conceal, making up for what Abigail does not or cannot express herself. Using journal pages like chapter titles, Fastvold and editor Dávid Jancsó skip over weeks at a time, showing the meaninglessness of entire days when Tallie does not visit. Daniel Blumberg’s music puts a fine point on emotions that would be best left open for interpretation. When his score goes on a manic saxophone jazz riff to capture a frenzied blizzard sequence, it breaks our immersion into the period’s surroundings. It becomes a Brechtian touch of post-modernism. At the same time, Chemetoff’s camerawork uses natural light and expansive backdrops shot in Romania to capture the frontier experience, and it’s undeniably gorgeous and transportive. The sound design, too, offers a realistic aural treatment of footsteps on hollow wooden floors and echoing interiors. But the period details seem offset by more modern theatrical displays, such as the choppy sex montage near the climax or the rapturous scene when Abigail sprawls her body out at the kitchen table after a visit from Tallie. It’s a beautiful-looking film that brought to mind how Nancy Kelly shot Thousand Pieces of Gold (1990), albeit with the added affectations found here.

The World to Come’s title infers a hopeless future for the women of this story, not to mention women over the next century-and-a-half. But it’s not as though patriarchal dynamics reached their zenith in the 1850s and gradually dissolved until they were gone as of today. Instead, the film’s commentary feels less immediate than Abigail’s urgent scenes with Tallie or remoteness with Dyer. But Fastvold also seems overly committed to pronouncing certain aspects of Abigail’s situation, including the obvious classical parallels between Abigail’s happiness and the changing seasons (sadness in winter, hope in spring, joy in summer, doom in fall). Beneath these overstated qualities is the familiarity of a story that has been revisited several times in recent years. And while the Western-style backdrop and terrific performances from the cast do much to keep the viewer invested—especially Waterston, who has rarely had such a substantial role—it cannot help but feel like a reaching attempt to match better films. Maybe that’s not fair. If viewed in isolation from more distinguished examples, The World to Come might play better. At this moment, however, it feels over-familiar and comparatively minor.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review