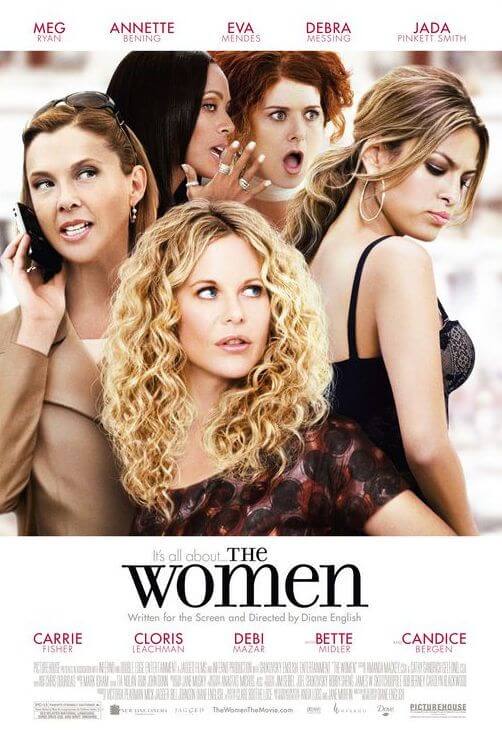

The Women

By Brian Eggert |

The Women began as Clare Boothe Luce’s hit 1936 Broadway play about Manhattan socialites, their love for shopping and Haute couture, and their penchant for gossip-mongering. George Cuckor, director of Gaslight and The Philadelphia Story, staying true to the source, adapted the play into a blithe 1939 film starring Norma Shearer, Joan Crawford, Rosalind Russell, Paulette Goddard, and Joan Fontaine—each one an incomparable screen icon. Cuckor’s black and white production boasted no men in the cast or background, and even included a fashion show mid-film shot in Technicolor (you know, for the ladies).

And now, Murphy Brown creator Diane English has adapted Luce’s play for a contemporary setting and, thankfully, also gives Cuckor’s film its due credit. Populated by a slew of female characters, all of which could be described as flighty and yammering but always well-dressed, the new film includes only women in the production. No male is seen for the duration. But despite the modernization of English’s take, her approach still relies on discussions (to which I’m oblivious) about shopping and modern labels—somewhat familiar for those of us who saw The Devil Wears Prada.

For example, the film opens with Annette Bening, who plays posh magazine editor Sylvia, hunting for bargains in Saks Fifth Avenue (an oxymoron in itself), scanning prices with a digital targeting readout built into her sunglasses. This is meant to be funny, I suppose, but it’s also a transparent appeal to present-day audiences that completely disregards the source’s spirit. Instead of fast-paced, wit-laden dialogue, we have sappy speeches about friendship and womanhood. Where the original saw the fun in callous, vindictive behavior, English tempers her screenplay to remain politically correct, even overemotional for the potentially comical material.

America’s Sweetheart no longer, Meg Ryan stars as Mary Haynes (the part originally played by Shearer), a wife, mother, and fashion designer who, with her absentmindedness, relies on her trusty housekeeper Maggie (the scene-stealing Cloris Leachman) to keep her life organized. Nevertheless, Mary’s husband is cheating on her with perfume spritzer girl, Crystal Allen (Eva Mendez, nowhere near the wickedness of Joan Crawford). Discovering the awful truth about her marriage, Mary luckily has friends there for support.

Debra Messing plays Edie, the disjointed mother who gets increasingly pregnant as the story progresses and ends the film with its most lively scene. We have a lesbian character, Alex (played by Jada Pinket-Smith), who whines about her supermodel girlfriend and could have added some backbone to the story had English allowed it. Candice Bergen makes a welcomed appearance as Mary’s wise mother. And cameos include Bette Midler, Carrie Fisher, and Ana Gasteyer. (Note: Despite these stars, I realized the material was just madcap enough for Diane Keaton, and her surprising absence was missed.)

After separating from her unseen husband, Mary loses herself in a slump, ignoring friends and family to a distressing degree. Reacting to this, her teenage daughter Molly (India Ennenga) decides she doesn’t want to be a woman and, in an awkward scene, burns her tampons in rebellion. Meanwhile, Mary’s friends aren’t doing much to help; they have their own problems, whereas in the original they were actively (and hilariously) plotting revenge on the adulteress. English’s script suggests vengeance is yesterday’s news, but if you expect audiences to escape into the affluence of the self-absorbed New York feminine elite, then why not make it completely escapist and allow for some cathartic payback?

English seeks to turn what was a lively comedy into a sort of funny melodrama with an overlong, frankly depressing second act, leading to a third that lacks vindication. She’s missing the point readily embraced by Cuckor: that each of Luce’s characters is a caricature sporting a snootily upturned nose and the ability to sling mud. Inside reprisals and deplorable behavior reside in Luce’s ridiculous, lovable satire. English attempts feminine empowerment for every role—a great message on its own, but not Luce’s, at least not in the softened, flaccid form English has conceived.

Unlock More from Deep Focus Review

To keep Deep Focus Review independent, I rely on the generous support of readers like you. By joining our Patreon community or making a one-time donation, you’ll help cover site maintenance and research materials so I can focus on creating more movie reviews and critical analysis. Patrons receive early access to reviews and essays, plus a closer connection to a community of fellow film lovers. If you value my work, please consider supporting DFR on Patreon or show your support in other ways.

Thank you for your readership!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review