The Woman King

By Brian Eggert |

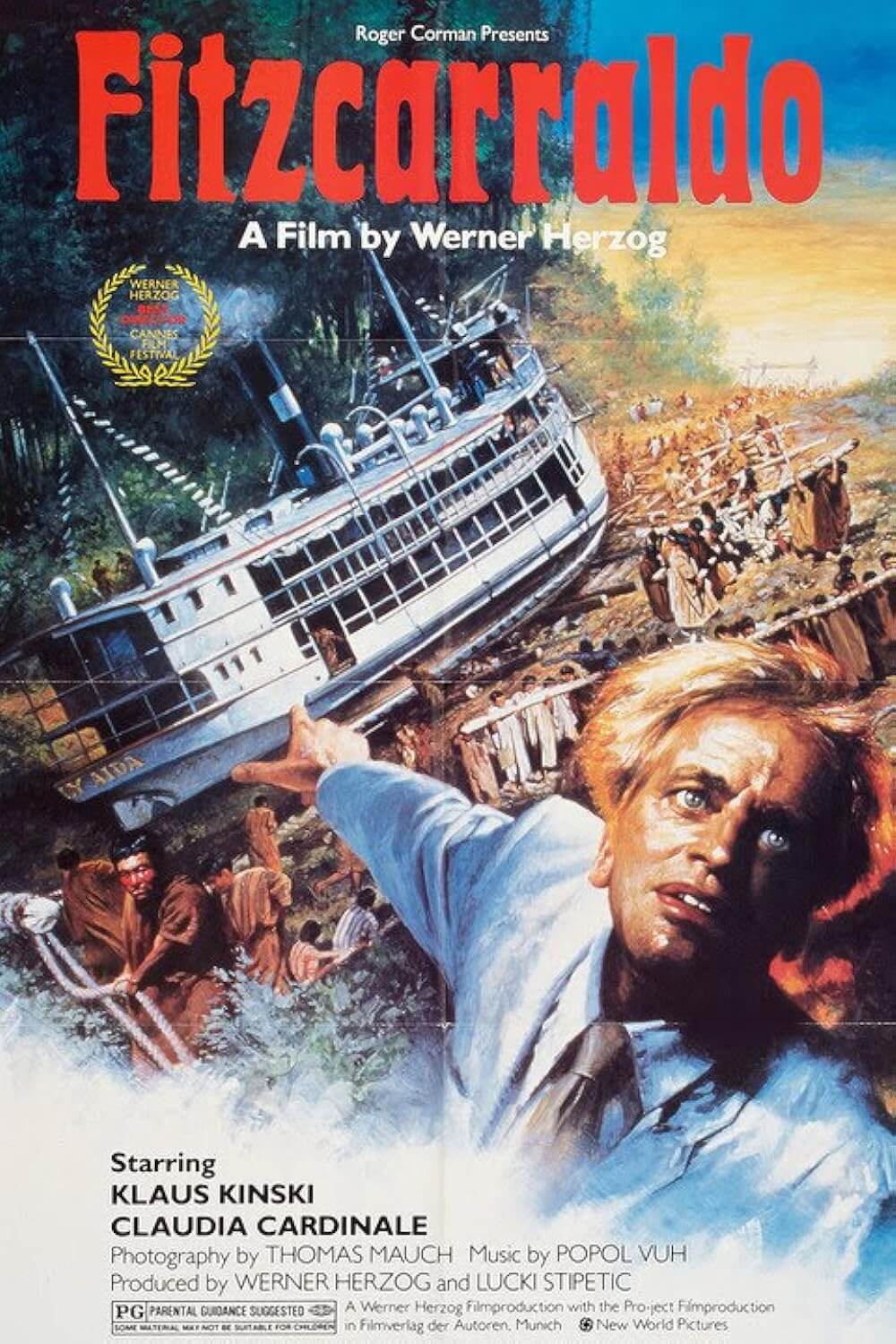

The Woman King marks the first Hollywood period epic set in Africa that’s not told from the subjectivity of colonizers. Sprawling titles from Zulu (1964), starring Stanley Baker and Michael Caine, to Werner Herzog’s Cobra Verde (1987) with Klaus Kinski, portray African kingdoms in a state of otherness, their citizens conveyed as anonymous savages to be conquered or enslaved by the British Empire or other European nations. Director Gina Prince-Bythewood’s film reframes history by centering on the Agojie—the all-female army tasked with defending the West African kingdom of Dahomey. The Portuguese slavers onscreen take on the roles of outsiders, exploitative and corrupting, and rightly cast as villains. By contrast, the Agojie are powerful, honorable, and fierce, and, headlined by Viola Davis, played by a cast of Black women who commands the screen. This historical account, based on the actual so-called Amazons active from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries, embraces the archetypal sword and sandals adventure and repositions its viewpoint. Even while conforming to genre conventions, The Woman King is passionate and exciting, beautifully filmed and acted, and easily among the best of its kind.

As the story goes, Maria Bello pitched the project to Davis while on stage, presenting the Oscar-winner with an award at the Skirball Cultural Center’s National Women’s History Museum in Los Angeles. Bello and fellow producer Cathy Schulman had the idea for an action movie starring a cast of Black women, and after a trip to Benin, the modern-day site of the former Dahomey kingdom, Bello found her concept, which also inspired the all-female Dora Milaje warriors of Wakanda in 2018’s Black Panther. Bello outlined her pitch, describing the Agojie and their strength, then asked the crowd, “Wouldn’t you want to see Viola Davis in a role like that?” The crowd responded with reported enthusiasm, and Davis jumped at the chance to co-produce and star. The team pitched the idea around Hollywood, but most studios turned them down. An all-Black cast in an expensive epic? It was unheard of, at least until Black Panther. Then, due to that MCU property’s massive commercial success, Sony’s TriStar green-lit the production. Prince-Bythewood joined to direct after proving her action chops in 2020’s The Old Guard for Netflix, one of the streaming platform’s most popular features. And, working with a budget of $50 million, Prince-Bythewood helmed the production on location in South Africa.

In one of her most transformative roles, Davis stars as General Nanisca, who leads the Agojie and reports only to King Ghezo (John Boyega). The King’s collective of wives jealously compete with Nanisca for his favor, but they don’t have the King’s ear or the kingdom’s future in mind as Nanisca does. When the film opens in 1823, Dahomey has kept the Oyo Empire at bay by selling them their people, which Oda (Jimmy Odukoya), the merciless Oyo leader, turns around and sells to the Portuguese. But Nanisca advises Ghezo to stop selling people to the Oyo Empire, knowing they’re amassing other tribes to overtake Dahomey. She suggests relying on their palm oil resources to generate income, thereby cutting ties with the Oyo and no longer contributing to the slave trade. Doing so prompts a war between the two parties—a conflict that draws from actual historical accounts. Indeed, in a less historically inclined version of The Woman King, the film would avoid the complicated issue of Dahomey’s part in the barbarity of slavery and deliver clear-cut heroes and villains. But the filmmakers have more on their minds than oversimplified storytelling for the masses.

In one of her most transformative roles, Davis stars as General Nanisca, who leads the Agojie and reports only to King Ghezo (John Boyega). The King’s collective of wives jealously compete with Nanisca for his favor, but they don’t have the King’s ear or the kingdom’s future in mind as Nanisca does. When the film opens in 1823, Dahomey has kept the Oyo Empire at bay by selling them their people, which Oda (Jimmy Odukoya), the merciless Oyo leader, turns around and sells to the Portuguese. But Nanisca advises Ghezo to stop selling people to the Oyo Empire, knowing they’re amassing other tribes to overtake Dahomey. She suggests relying on their palm oil resources to generate income, thereby cutting ties with the Oyo and no longer contributing to the slave trade. Doing so prompts a war between the two parties—a conflict that draws from actual historical accounts. Indeed, in a less historically inclined version of The Woman King, the film would avoid the complicated issue of Dahomey’s part in the barbarity of slavery and deliver clear-cut heroes and villains. But the filmmakers have more on their minds than oversimplified storytelling for the masses.

Much of the narrative entails a defiant young woman, Nawi (Thuso Mbedu), who refuses to become the wife-property of a husband. Instead, her father gives her to the kingdom, which enlists her in Agojie training alongside dozens of other recruits. Nawi learns from the resident trainer, Izogie (Lashana Lynch), a good-humored but vicious warrior, how to fight and think like an Agojie in rigorous training sequences. But Nawi clashes with Nanisca at first, pointing out the hypocrisy of male soldiers who can take wives, yet the Agojie cannot take husbands or have children. Nawi has also had a hard life and wants recognition for her pain. “To be a warrior, you must kill your tears,” Nanisca tells her, reflecting the constant internal struggle of each woman in her army. Nawi has much to consider, whether it’s her orphan upbringing or the arrival of Malik (Jordan Bolger), whose father was European and whose mother was from Dahomey. Accompanying the white slave trader Santo Ferreira (Hero Fiennes Tiffin), who works closely with the Oyo, Malik presents a potential star-crossed romantic figure to Nawi. But their would-be forbidden love is an emotional temptation and symbol of the sacrifices the Agojie must make for their unity and sisterhood. Indeed, Nawi is warned not to give her power away to a man, even if Malik is tragically split between two worlds—evidenced by the ultimate symbol of cultural colonization, the crucifix, dangling on his neck.

Prince-Bythewood draws from the wellspring of Braveheart (1995) and Gladiator (2000), epics invested in character depth as well as exciting battle sequences. But rather than those Ridley Scott-esque war scenes, complete with armored combatants clanging in battle and swooshing camerawork, Prince-Bythewood keeps the action grounded and efficient. The Woman King’s soldiers have sleek, oiled physiques, allowing them to be fast and deadly; their battle scenes prove just as streamlined and not weighted down by iron. Editor Terilyn A. Shropshire renders the battles in ground-level sequences that showcase the brutal, quick movements of the Agojie, who use deadly machetes, spears, acrobatic attacks, and sharpened fingernails to take out their enemies. Although The Woman King is rated PG-13 and avoids much of the blood and gore associated with the genre, the fight choreographer Daniel Hernandez, whose work can be seen in The Old Guard and several MCU entries, delivers fast-paced and thrilling combat scenes. But they don’t outshine the dimensional characters, who could have been impenetrable given how the people of Dahomey must not look at them directly when they return from a mission, thus instilling their mythic status in the kingdom. Instead, the screenplay by Dana Stevens, developed with Bello, gives them a depth of humanity that goes beyond the usual objectives seen in such epics—duty, honor, and revenge.

Since her directorial debut with Love & Basketball (2000), Prince-Bythewood has explored characters with respect for their inner lives, and The Woman King is no exception. The filmmaker balances grand set pieces with character introspection, bringing out several terrific performances. Central are Nanisca and Nawi. They each have individual conflicts to overcome in their dynamic as General and soldier, but they also have a deeper bond that enhances their relationship. Mbedu (31, despite looking 13) plays her scenes with equal measures of ferocity, sensitivity, and intelligence, and she holds her own opposite Davis’ powerhouse presence. Mbedu is the breakout here, delivering a star-making performance. Still, Davis lends her considerable talent to General Nanisca, whose past is marked by her capture and rape by Oda nearly 20 years earlier. Scarred and weathered, Nanisca could have been a singular and unstoppable force, but Davis and her director turn the character into someone who uses her trauma to sharpen her fierceness as a military leader and tactician. Prince-Bythewood gives Davis’ performance room to breathe. Although Nanisca gives some rousing battle cries and speeches (“We are the spear of victory! We are the blade of freedom! We are Dahomey!”), the most powerful moment is a scene of quiet solitude near the end when Nanisca processes an aching moment with Nawi. Besides Davis and Mbedu, Lynch’s endearing and imposing presence is deeply felt (stay for a mid-credits scene) and may become the audience favorite.

Since her directorial debut with Love & Basketball (2000), Prince-Bythewood has explored characters with respect for their inner lives, and The Woman King is no exception. The filmmaker balances grand set pieces with character introspection, bringing out several terrific performances. Central are Nanisca and Nawi. They each have individual conflicts to overcome in their dynamic as General and soldier, but they also have a deeper bond that enhances their relationship. Mbedu (31, despite looking 13) plays her scenes with equal measures of ferocity, sensitivity, and intelligence, and she holds her own opposite Davis’ powerhouse presence. Mbedu is the breakout here, delivering a star-making performance. Still, Davis lends her considerable talent to General Nanisca, whose past is marked by her capture and rape by Oda nearly 20 years earlier. Scarred and weathered, Nanisca could have been a singular and unstoppable force, but Davis and her director turn the character into someone who uses her trauma to sharpen her fierceness as a military leader and tactician. Prince-Bythewood gives Davis’ performance room to breathe. Although Nanisca gives some rousing battle cries and speeches (“We are the spear of victory! We are the blade of freedom! We are Dahomey!”), the most powerful moment is a scene of quiet solitude near the end when Nanisca processes an aching moment with Nawi. Besides Davis and Mbedu, Lynch’s endearing and imposing presence is deeply felt (stay for a mid-credits scene) and may become the audience favorite.

If The Woman King adheres to a conventional epic format and sometimes feels familiar in its uses of villains, obligatory speeches, and political intrigue, its cultural perspective and main characters transcend what most moviegoers associate with historical adventures. Prince-Bythewood delivers the best film of her career thus far, reaching beyond her previous work with complex characters, a visual treatment of considerable scope and scale, and a new landmark in the genre. Even while using traditional tropes, she enlivens them with subjectivity and a perspective never before seen in this kind of epic. By the end, the film’s theme that the Agojie are stronger and can better fight oppression because they remain psychologically unbound reaches into the contemporary world, speaking to women and people of color who historically have had their power taken from them by inspiring them with the Agojie’s strength and solidarity. But The Woman King is also bound to please crowds, regardless of race or gender, just as it celebrates these powerful Black female warriors. Quite simply, this is great filmmaking and exhilarating entertainment, and it’s sure to be remembered as a milestone.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review