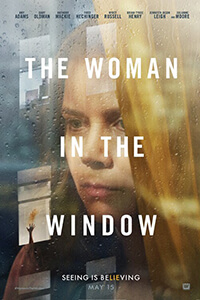

The Woman in the Window

By Brian Eggert |

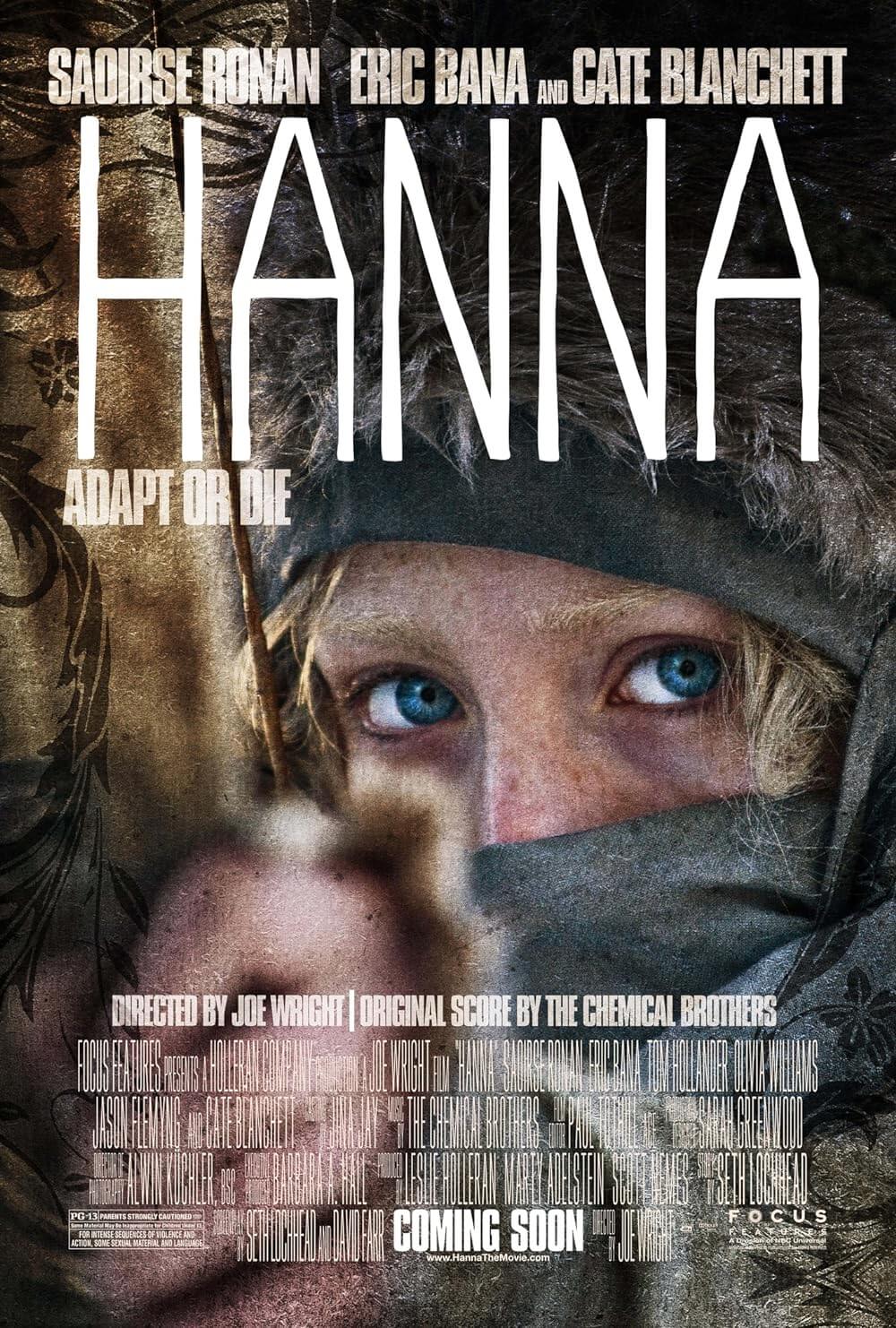

The Woman in the Window assembles one of the best groups of prestige talent you’ll see in any 2020 movie. Amy Adams takes the lead alongside Gary Oldman, Julianne Moore, Jennifer Jason Leigh, Brian Tyree Henry, and Wyatt Russell. It was directed by Joe Wright, helmer of such credible fare as Atonement (2007) and Darkest Hour (2017). The script, an adaptation of the 2018 best-selling book, was written by Tracy Letts, the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright of August: Osage County (2013) and the juicier, chicken-fried noir Killer Joe (2011). Cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel, who has worked with the Coen brothers, Julie Taymor, and Jean-Pierre Jeunet, shot the film with undeniable style. The prolific Danny Elfman, Hollywood’s go-to composer, wrote the score. But none of these supremely talented people can help A.J. Finn’s source material, a book so derivative and predictable that it fails to have any life of its own. Instead, the screen version reduces an already overly familiar scenario into a series of plot points and red herrings, carried out by underdeveloped characters and capped by a sloppy climax.

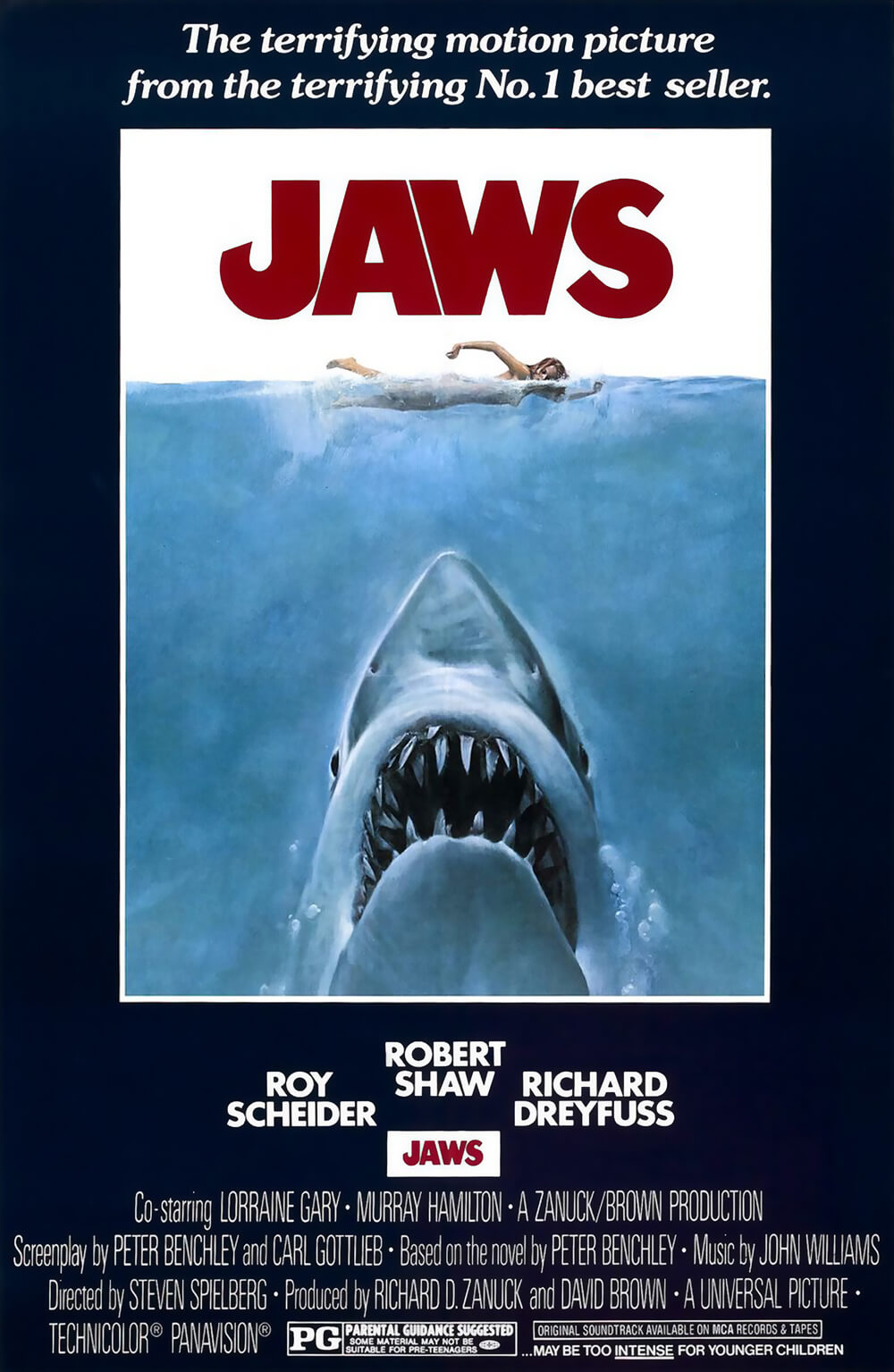

At the very least, Wright offers an immediate visual nod to Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window (1954), the obvious comparison piece, which is more than Finn did to acknowledge his book’s inspiration. The story follows Dr. Anna Fox (Adams), a troubled child psychologist who lives in a massive brownstone in Harlem, which she never leaves due to chronic agoraphobia and anxiety. Separated from her husband (Anthony Mackie) and daughter (Mariah Bozeman), Anna spends her days roaming around her house, mixing prescription medications with untold bottles of wine, and watching old movies. Rear Window makes an appearance in the first scenes in Wright’s hands; Finn’s book barely referenced the movie, despite Anna having an encyclopedic knowledge of classic thrillers. It was a conspicuous omission, too, given that, like James Stewart’s wheelchair-bound character, Anna sees a murder out her window while practicing some casual voyeurism.

Anna believes Alistair Russell (Oldman), her hot-headed new neighbor across the street, has killed his wife Jane (Moore). She learns from Jane that Alistair has a short temper, which Anna witnesses when he confronts her about talking to his sensitive teenage son, Ethan (Fred Hechinger). But her credibility as a witness comes into question when a pair of detectives (Brian Tyree Henry and Jeanine Serralles) question her wine intake and fragile mental state. Moreover, Anna has no evidence of a crime since Alistair has found a look-alike for his wife (Leigh). The movie establishes any number of potential culprits: Alistair, the possessive and abusive husband; David (Russell), Anna’s mysterious tenant with a history of violence; Ethan, the boy who supposes Anna’s job as a child psychologist involves counseling for “school shootings or torturing”—an alarming assumption. Or maybe it’s Anna herself, considering she spends most of her time in an overstimulated and hallucinatory state.

Indeed, Wright presents an unreliable main character by inserting fragmentary images from Anna’s mind, which anticipate a twist that comes far too early (about an hour) into the proceedings. The moment gives Adams a scene that showcases her powerhouse talent, but it does little to deepen the character or advance the story in Letts’ adaptation. Everything about The Woman in the Window has been boiled down to plot points. Wright and editor Valerio Bonelli rush through exposition and choppily present action, giving the audience no time to care. It feels like an abridged version of a two-and-a-half-hour movie, edited down to meet some studio-prescribed formula runtime for an effective thriller. Scenes feel rushed and sharply cut, with no time to breathe or create an atmosphere. Odd moments that border on fantasy—such as CGI blood spattering on the camera as though Anna witnessed the murder up-close instead of fifty yards away—feel weirdly inserted into the mix.

Indeed, Wright presents an unreliable main character by inserting fragmentary images from Anna’s mind, which anticipate a twist that comes far too early (about an hour) into the proceedings. The moment gives Adams a scene that showcases her powerhouse talent, but it does little to deepen the character or advance the story in Letts’ adaptation. Everything about The Woman in the Window has been boiled down to plot points. Wright and editor Valerio Bonelli rush through exposition and choppily present action, giving the audience no time to care. It feels like an abridged version of a two-and-a-half-hour movie, edited down to meet some studio-prescribed formula runtime for an effective thriller. Scenes feel rushed and sharply cut, with no time to breathe or create an atmosphere. Odd moments that border on fantasy—such as CGI blood spattering on the camera as though Anna witnessed the murder up-close instead of fifty yards away—feel weirdly inserted into the mix.

The Woman in the Window is the kind of material that another filmmaker, like Brian De Palma, could have made into a memorable thriller. De Palma understands how Hitchcock built suspense through patience and elaborate set-ups, and he’s made several Hitchcockian homages—including two riffs on Rear Window with Sisters (1972) and Body Double (1984). Unfortunately, Wright’s impatient, over-eager style here fails to engage the audience or create an ample mystery or tension. He’s too interested in delivering a fast-paced viewing experience. The movie races through scenes that should be developing characters and establishing suspicion; rather, it lays out the suspects in clinical fashion, as though Wright and Letts drew out a thriller’s bones but had no idea how to give it flesh. The big-name cast, then, is saddled with underwritten characters who have no inner life.

Somehow, it makes perfect sense that The Woman in the Window was originally slated for a 2019 release. After the Disney-Fox merger and several delays to the movie’s release, coupled with the COVID-19 pandemic, The Woman in the Window ended up at Netflix, where it feels right at home with their vast inventory of undercooked original content. All of this is made worse by the fact that there’s endless potential here. Adams could have given Anna psychological depth; she’s well versed in portraying complex, damaged characters in Arrival or Nocturnal Animals, both from 2016. And though we see glimmers of a better role, her performance is cut short by Wright’s insistence on plot over character. The movie’s biggest crime is that Wright doesn’t have the good sense to make the proceedings into a fun or scary whodunit. He robs us of any joy the spectator usually gets from this sort of thing, leaving us unmoved and unengaged—the worst outcome a thriller could offer.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review