The Woman in the Fifth

By Brian Eggert |

After directing the 2004 teen romance My Summer of Love, which introduced Emily Blunt and Natalie Press, Polish-born filmmaker Pawel Pawlikowski completed two-thirds of an adaptation of Magnus Mills’ novel The Restraint of Beasts. During the production, however, Pawlikowski’s wife had become seriously ill, and he canceled all work on that film to care for her and his children. After her regrettable passing, the Paris-based filmmaker moved on to another project entirely, this one from an original screenplay. With this in mind, his film The Woman in the Fifth becomes a haunting mix of poetic imagery and overlapping emotions, clearly drawn from Pawlikowski’s feelings as an artist grieving for someone he loved deeply. The result is something akin to an elegiac and surreal ghost story, but it’s as evocative as it is unsolvable.

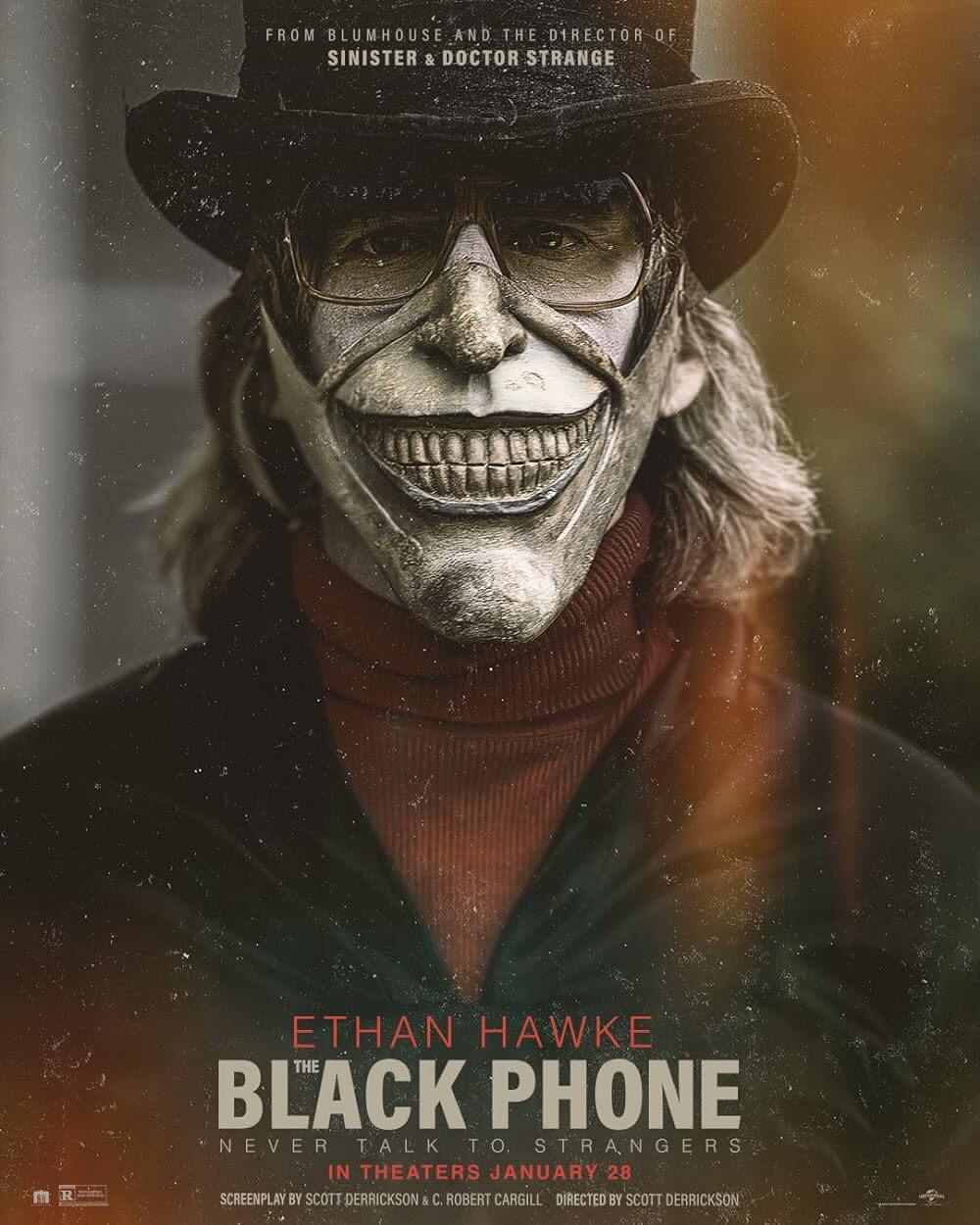

The opening scenes set the mood perfectly. Ethan Hawke’s gaunt American novelist Tom Ricks arrives in Paris to reconnect with his wife Nathalie (Delphine Chuillot) and their six-year-old daughter Chloe (Julie Papillon). His intentions seem noble enough until we see Nathalie’s reaction to his arrival: she’s filled with apprehension at his presence, and quickly calls the police to enforce the restraining order she’s taken out against him. When he speaks briefly with Chloe, Tom finds her mother has told her that he’s been away in prison and that the police are after him. Tom says that’s incorrect; he was away recovering in a hospital. But recovering from what? Or, if you believe Nathalie, why was he in prison? These questions are just the beginning. Soon we hear police sirens and Tom makes a run for it. He finds himself on a bus to who-knows-where; he’s fallen asleep and reached the end of the line, but his wallet and bags were stolen.

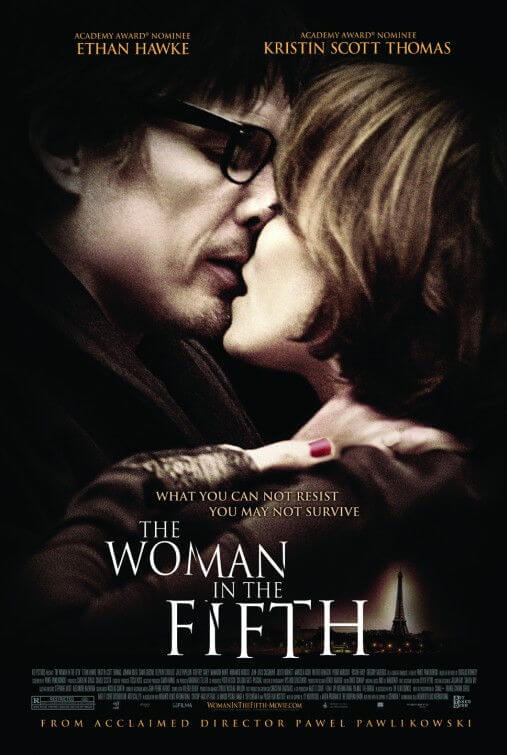

Broke, Tom asks for help from shoddy lodgings owner Sezer (Samir Guesmi), who agrees to give the American stranger a room if, in exchange, he accepts a night watchman post in Sezer’s questionable business warehouse. Tom spends nights screening people via security camera who enter a room for who-knows-what despicable purpose. Meanwhile, when Tom is spotted as the known author of his sole novel—titled Downside Up, although Tom says it’s called “Forest Light”—he attends a gathering of literary types, where he meets self-proclaimed writer’s muse Margit Kadar (Kristin Scott Thomas), a half-Hungarian, half-French seductress who wastes no time bedding Tom. He returns again and again to her titular flat number five, where she encourages him to write while he laments his situation and admits he feels like “a sad double” of his actual self. With comments like this, Tom’s status as an unreliable narrator becomes increasingly suspect.

Sezer’s barmaid and lover, Ania (Joanna Kulig), quickly takes a liking to Tom too. She’s reading his book and falls for its author, recounting back to him the imagery he uses, which Pawlikowski shows us. We see a dark, picturesque forest strewn with crimson boxelder bugs and the decimated body of some grisly murdered victim. Are these images from Tom’s book or images from his past? Pawlikowski’s film seems to alternate between Tom’s life and the life of his novel, although the viewer must determine which is which, or if they’re at all separate. Soon we question everything, as the surreality becomes almost Kafkaesque with Tom’s sudden arrest, a brutal murder, Chloe’s sudden disappearance, and the revelation that at least one (but possibly more) of the aforementioned characters are dead. Don’t attempt to rationalize what you see; instead, allow the confounding yet affecting atmosphere to pass over you like a fog of sadness and dread.

Most effective is Scott-Thomas, whose elusiveness and confidence lend her character an indefinable aura. But The Woman in the Fifth belongs to Hawke’s grave expressions; he captures an indefinable woe, suspicion, sympathy, and paranoia that hasn’t been so effectively communicated in this format since Roman Polanski’s oddly circular horror masterpiece The Tenant (1976). With Polanski as an obvious influence here, Pawlikowski creates a comparable feeling for the audience in that we almost understand what’s happening to Tom, but it remains elusive enough to maintain its own mysteries and our interest at the same time. Then again, it must be said that some moviegoers will be left scratching their heads as to what it all means. And though Pawlikowski doesn’t share the morbid sense of humor that makes Polanski’s films so enjoyable and accessible, his own embrace of poetic gravity has a certain mesmerizing quality that a select group will find enchanting.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

Thank you for visiting Deep Focus Review. If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your movie watching—whether it’s context, insight, or an introduction to a new movie—please consider supporting it. Your contribution helps keep this site running independently.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review