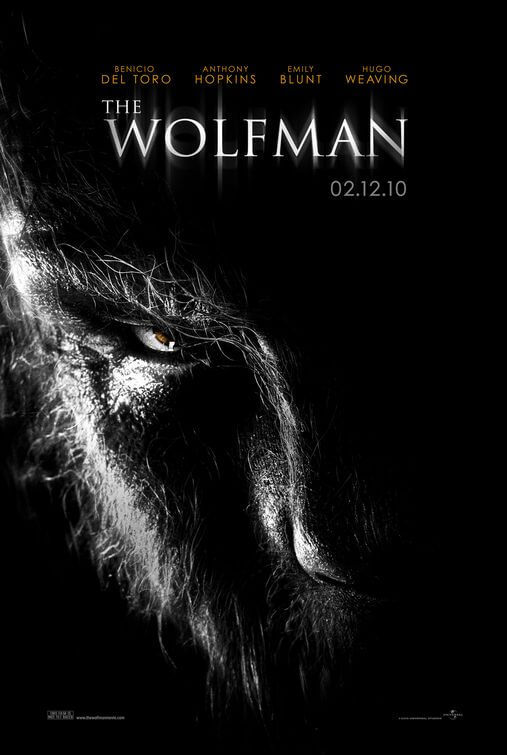

The Wolfman

By Brian Eggert |

The werewolf gets a bum rap. Since the 1941 original The Wolf Man, the film that invented our modern concept of the creature, the werewolf has been rendered in dozens of shoddy horror movies. It used to be that the werewolf represented the duality of the human mind, the inner monster—it was a curse that offered a window into the nature of man. Nowadays, werewolves are more frequently seen as the opponents of vampires, to be represented in humdrum computer-generated battles. Few werewolf films, today or otherwise, compare to the original, and almost none contain the same thematic or emotional consequence written into the narrative. Most are content to be special FX vehicles, wherein the werewolf’s presence is reduced to a means for cheap thrills.

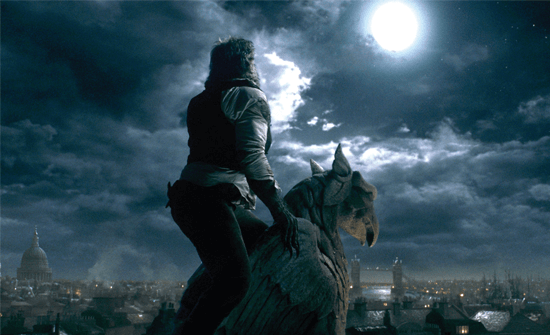

Universal Studio’s remake The Wolfman attempts to refashion the original film for modern audiences by staying true to the monster’s inherent lesson about duality, but also by supplying plenty of violence and gore for moviegoers seeking cheap thrills. Instead of modernizing the setting, however, the filmmakers made the brave and welcome choice of setting the film in Victorian London, a dark and foggy place that emanates the appropriate atmosphere of gothic horror. There’s a near-perfect balance of classicism embedded into the scenery and modernized horror bloodshed gushing from the story, enough to please apologist horror fans. And yet, there’s something missing from the characters in this setting that prevents the film from truly succeeding the way it should have.

This is an important film for Universal Studios, a step in the right direction of reclaiming its status as the premier monster movie studio. They’ve lost their grip on that standing since the 1950s, and now they’re returning to Golden Age classics like Dracula, Frankenstein, and The Bride of Frankenstein. They tried to squeeze out every penny in one failed grasp with Van Helsing in 2004, a movie that pitted Hugh Jackman against dull computer-generated versions of the Universal monsters. Anyone who saw that dud knows instantly why it failed, for the same reasons that their rehash The Mummy from 1999 failed in a creative sense (though it was a blockbuster financially). Instead of making a creaky, spooky horror movie, in both cases, their director, Stephen Sommers, made an overblown B-grade action movie.

Within the first scenes of this remake, the audience knows they won’t be enduring your typical revision of a classic horror icon—it doesn’t look like Wes Craven’s Cursed or Dracula 2000. This production is top-notch, even if there were problems behind the scenes. But more on that later. There’s always a fog on the moors. The backdrop is damp, murky, and ominous. The characters appear worn and tired, heavy with sorrows that the script doesn’t begin to explain. The exact setting is 1891 in rural England, where Ben, the son of Sir John Talbot (Anthony Hopkins), has disappeared. Sir John’s other son, London stage actor Lawrence Talbot (Benicio Del Toro), receives a letter from Ben’s fiancée, Gwen Conliffe (Emily Blunt), to come and help find his brother. By the time Lawrence arrives at Talbot Hall, Ben’s body has been found, mutilated by what the locals believe is some awful beast of the moors.

Within the first scenes of this remake, the audience knows they won’t be enduring your typical revision of a classic horror icon—it doesn’t look like Wes Craven’s Cursed or Dracula 2000. This production is top-notch, even if there were problems behind the scenes. But more on that later. There’s always a fog on the moors. The backdrop is damp, murky, and ominous. The characters appear worn and tired, heavy with sorrows that the script doesn’t begin to explain. The exact setting is 1891 in rural England, where Ben, the son of Sir John Talbot (Anthony Hopkins), has disappeared. Sir John’s other son, London stage actor Lawrence Talbot (Benicio Del Toro), receives a letter from Ben’s fiancée, Gwen Conliffe (Emily Blunt), to come and help find his brother. By the time Lawrence arrives at Talbot Hall, Ben’s body has been found, mutilated by what the locals believe is some awful beast of the moors.

Lawrence’s search for his brother leads him to a gypsy camp that’s immediately attacked by the beast. He’s bitten but survives the ordeal, only to learn from the gypsy woman Maleva (Geraldine Chaplin) that he’s cursed to become a half-man, half-wolf, prowling the night for prey while baying at the full moon. Sure enough, the next full moon, he’s doing just that. But here is where the story gets more involved than the original, because Lawrence is eventually captured by authorities, namely Inspector Abberline (Hugo Weaving), and brought to London to be examined in an asylum that believes him a lunatic. Of course, they learn very quickly his curse is not merely a delusion.

Writers Andrew Kevin Walker (Sleepy Hollow) and David Self (Road to Perdition) extend the plot of the original film quite far, doing so with some ingenuity that deepens the characters with a twist. To be sure, the right actors were chosen to complement the writing. Del Toro may not look like Lon Chaney Jr., but he does have a wolflike visage, and he’s capable of handling the weighty presence of his character. Although, the audience doesn’t have a connection with Lawrence Talbot, as the film doesn’t take the time to make a bond between the character and the audience before he’s sprouting fangs and wolf hair. The same can be said for Weaving, who has an intriguing role as Abberline (the same investigator of the ‘Jack the Ripper’ murders), though not much is done with the character. Blunt’s role is barely developed; Gwen’s motivations and eventual romantic interest in Lawrence feel obligatory and forced. Hopkins, though, steals the show in an intense role, this being his second gothic horror remake of a classic monster movie, the other being Francis Ford Coppola’s highly underrated Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

Even if the characters don’t have that much presence, the monster effects and associated violence are filmed with undeniable style. Rick Baker, the makeup guru behind every major werewolf movie of the last thirty years (from An American Werewolf in London to The Howling to Wolf), chose to render the Wolf Man in a form comparable to the original. A hulking man-beast, Del Toro’s monster looks much like a contemporized version of the 1941 concept from Jack Pierce. While noble from an homage standpoint, the man-beast doesn’t look quite right for today’s audiences, and the traditional appearance gives the creature a campy edge. The computer-generated scenes of the monster—used mostly when it’s running or attacking or transforming—look decent, but they won’t impress you (neither will the lousy CGI bear and deer). Still, there’s plenty of bloodshed, limbs lost, decapitations, and guts spilled, if that’s your thing. All the effects in the film, both makeup and computer, are simply serviceable.

It’s no secret that the production of The Wolfman was a troubled one, and director Joe Johnston has been surprisingly open about the behind-the-scenes complications—they’re much less scandalous than one would expect. Johnston was hired when the original director, Mark Romanek (One Hour Photo), left the production due to the ever-ambiguous “creative differences” with Universal in 2007. In doing so, Johnston stepped onto a major studio film that was three weeks away from shooting principal photography, though he contends that Romakek made some smart decisions and provided the groundwork for his own interpretation. Still, there were changes in the script and the structure of the film. After shooting, the extensive post-production process met with delay after delay, when the wavering studio teeter-tottered on decisions surrounding the film’s budget, special FX sequences, and musical score.

A chase sequence through London was cut from the script before completion, so the themes in composer Danny Elfman’s original score no longer fit the overall picture. The studio then demanded modern electronic music, completed by Paul Haslinger, to accompany the shorter film. But Johnston fought Haslinger’s period-inappropriate score, and it was removed altogether when the filmmakers decided to include the London chase sequence, after all, thus adding to the runtime and making the Haslinger music obsolete. After necessary reshoots, Elfman was brought back to reformat his initial score to fit the new runtime. What’s more, in this shuffle to find their structure, the filmmakers scrapped much of makeup man Rick Baker’s physical designs, relying instead on heavy strokes of CGI to avoid the time-consuming hassle of traditional makeup application.

A chase sequence through London was cut from the script before completion, so the themes in composer Danny Elfman’s original score no longer fit the overall picture. The studio then demanded modern electronic music, completed by Paul Haslinger, to accompany the shorter film. But Johnston fought Haslinger’s period-inappropriate score, and it was removed altogether when the filmmakers decided to include the London chase sequence, after all, thus adding to the runtime and making the Haslinger music obsolete. After necessary reshoots, Elfman was brought back to reformat his initial score to fit the new runtime. What’s more, in this shuffle to find their structure, the filmmakers scrapped much of makeup man Rick Baker’s physical designs, relying instead on heavy strokes of CGI to avoid the time-consuming hassle of traditional makeup application.

What’s evident in the final film is that there was some creative flip-flopping going on behind the scenes. Subplots feel patchy and underdeveloped, and the beginning feels rushed to get Talbot attacked and the werewolf curse pulsing through his veins. That’s no fault of Johnston, who claims a “Director’s Cut” will appear on home video and feature scenes that build the relationships of the characters more thoroughly. Perhaps that’s the cut to see, although whether that will solve the problems of the film remains to be seen. The main problem inhabits in the editing, re-editing, and re-reediting. Something is bound to be lost in the process of going over the same film over and over for two years; the audience may feel a certain distance from the material because of it.

But The Wolfman is not a disaster by any means, whereas another film put through the same rigmarole might not have fared so well. Johnston’s direction, however workmanlike, gets the job done—though undoubtedly, a more visionary director would’ve been a better choice and perhaps would’ve fought for the necessary scenes to build the film’s characters. Enjoying the somewhat cheesy, B-movie exploits on an aesthetic level is easy, as the 19th-century gothic airs have a beautiful darkness to them, comparable to the look of Sleepy Hollow or Hammer horror films. Where the film suffers is its lack of involvement in the crucial levels of emotion and suspense, the driving forces of the original film. Had those essential elements of the story been developed further, this would be an effortless recommendation. As is, you might want to wait for Johnston’s Director’s Cut.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review