The Wolf of Wall Street

By Brian Eggert |

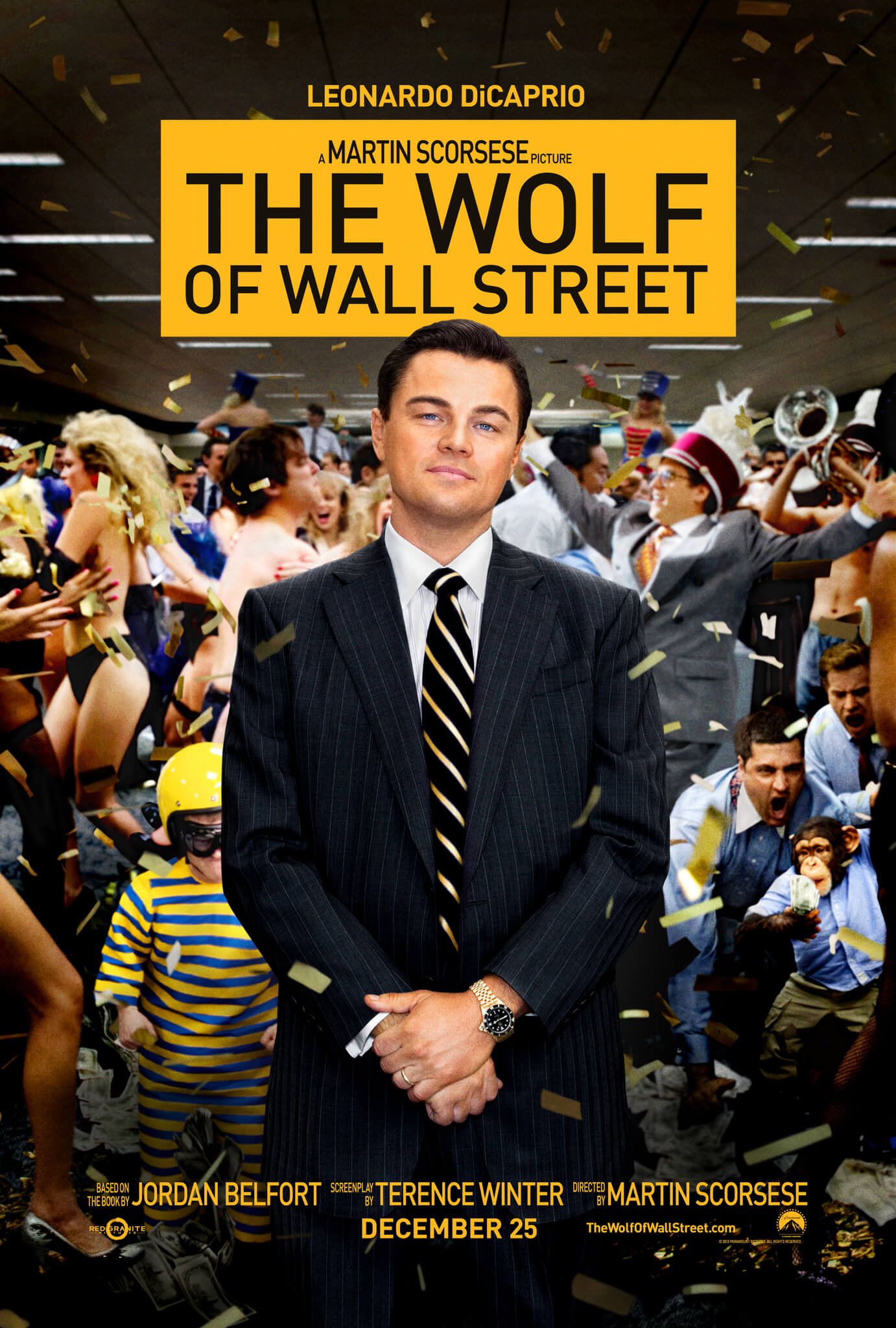

A marathon of euphoric decadence fuelled by copious amounts of drugs, sex, and an amazing performance at its center, The Wolf of Wall Street represents Martin Scorsese at his most exuberant, spinning a tale of American hedonism that revels in the profane, hilarious, and horrible behavior of its stockbroker characters. Based on the memoir of Jordan Belfort, whose financial exploits made him a multi-millionaire at the age of 26, the screenplay by Terrence Winter (Boardwalk Empire and The Sopranos) follows a similar narrative trajectory as Goodfellas and reflects the extremes of a capitalistic society that turns on itself through excess. Scorsese’s three-hour bacchanal unapologetically courses through the infectious appeal of Wall Street indulgence by way of Belfort, a fascinating anti-hero and self-described “Bond villain” of Caligula-esque proportions, played with unruly animation by Leonardo DiCaprio. Although, like Goodfellas, the film ends with Belfort’s slight ruination and fond memories of his former lifestyle, this is not a film about its main character’s redemption or casting a moralist stone at the proceedings. Rather, Scorsese considers what has drawn the character to this way of life and fills us with lament when it’s over, and not lament for the unscrupulous behavior but for the limelight which has passed.

Throughout, Scorsese reproduces Rome before the fall in a neverending series of sexual debaucheries and drug-addled exploits, all of it at once galvanizing and repulsive. DiCaprio’s almost constant, playful voiceover narrates Belfort’s story, beginning at his prime and then taking us back to the beginning, in the late 1980s when, just before the Black Monday crash of 1987, Belfort received his broker’s license. Though mentored as a green-faced “connector” (e.g. phone dialer) over a three-martini lunch by Matthew McConaughey’s sleazy L.F. Rothschild trader, Belfort soon finds himself out of work in a market where job openings for stockbrokers are few and far between. He answers an ad for a strip mall-set penny stock outfit (run by an uncredited Spike Jonze), a racket where commissions are fifty percent of each transaction due to the cheapness of the stock. From this, Belfort dreams up his own stately sounding company called “Stratton Oakmont” and writes a successful cold-call, high-pressure sales script for his boiler room of shady, inexperienced salesmen—comprised of drug dealers, high-school dropouts, and dim-wits—all of whom make it rich by “selling garbage to garbagemen.” Their operation rises in the ranks of Wall Street when Belfort’s merry staff tempts whale buyers with blue chip stocks, but then sells them millions in worthless penny stocks for higher commission rates.

In Oliver Stone’s Wall Street (1987), Gordon Gekko famously argued, “Greed is good.” Belfort wouldn’t disagree, except he’s invariably less concerned with debating this point to a room full of investors than he is with experiencing the benefits of endless riches first-hand. He’d rather chant “Gooble-gobble, we accept you, one of us!” from Freaks (1933) after negotiating how to best catapult a little person onto a target. Alongside his oddball business partner Donnie Azoff (Jonah Hill, behind hilarious white-capped teeth and glasses with clear lenses to look smarter), Belfort encourages Stratton Oakmont’s alpha-male office routine of abundant drug use, sales war cries, and prostitutes (eventually, restroom signage bans office sex during business hours), while in his personal life he’s an admitted addict, dependent on a steady intake of illegal substances, bedroom debauchery, and the most addicting drug of all: Money. As Belfort becomes a millionaire dubbed “The Wolf of Wall Street” in a Forbes article, he ditches his former middle-class wife (Cristin Milioti) for a blonde model named Naomi (Margot Robbie) and an endless party lifestyle. Meanwhile, FBI agent Patrick Denham (Kyle Chandler) targets Belfort and Stratton Oakmont in an investigation, inciting Belfort to rely on a number of friends and relatives (played by Rob Reiner, Jon Favreau, Joanna Lumley, and Jean Dujardin, all excellent) to protect his money and shield him from legal culpability.

In Oliver Stone’s Wall Street (1987), Gordon Gekko famously argued, “Greed is good.” Belfort wouldn’t disagree, except he’s invariably less concerned with debating this point to a room full of investors than he is with experiencing the benefits of endless riches first-hand. He’d rather chant “Gooble-gobble, we accept you, one of us!” from Freaks (1933) after negotiating how to best catapult a little person onto a target. Alongside his oddball business partner Donnie Azoff (Jonah Hill, behind hilarious white-capped teeth and glasses with clear lenses to look smarter), Belfort encourages Stratton Oakmont’s alpha-male office routine of abundant drug use, sales war cries, and prostitutes (eventually, restroom signage bans office sex during business hours), while in his personal life he’s an admitted addict, dependent on a steady intake of illegal substances, bedroom debauchery, and the most addicting drug of all: Money. As Belfort becomes a millionaire dubbed “The Wolf of Wall Street” in a Forbes article, he ditches his former middle-class wife (Cristin Milioti) for a blonde model named Naomi (Margot Robbie) and an endless party lifestyle. Meanwhile, FBI agent Patrick Denham (Kyle Chandler) targets Belfort and Stratton Oakmont in an investigation, inciting Belfort to rely on a number of friends and relatives (played by Rob Reiner, Jon Favreau, Joanna Lumley, and Jean Dujardin, all excellent) to protect his money and shield him from legal culpability.

In his fifth collaboration with Scorsese (after Gangs of New York, The Aviator, The Departed, and Shutter Island), DiCaprio displays an intensity unlike anything he’s accomplished before, ranging from despicable lows to physical comedy of a rare sort. There’s a gut-achingly hilarious scene where Belfort must get home to stop Donnie from talking on his FBI-tapped phone, but he finds himself so incapacitated by Quaaludes (the film’s drug of choice) that he must crawl across the ground to his sports car like an infant. The scene is fuelled by our strange sense of dread over our hero’s capture and the raw hilarity of his silly, Popeye-inspired break from his stupor. DiCaprio’s commitment to Belfort’s rousing rally the troops speeches and more self-deprecating moments of sexual humiliation are both priceless and fearless, but the performance is not devoid of quieter, cleaner touches of sobriety. It’s a manic performance of extreme highs, ridiculous behavior, and carefully placed nuances that should deservedly earn DiCaprio an Academy Award nomination (if not the Oscar itself). Take the wonderful intricacy in the scene where Belfort invites Denham on his massive yacht and cautiously offers a bribe, the conversation transforming out of Belfort’s control, illustrating how he exists in his own little larger-than-life fantasy where money solves everything, but doesn’t.

Scorsese is known for gritty crime dramas and heavy explorations of flawed, dangerous characters—he’s not known for comedies, though his films The King of Comedy and After Hours represent the rare, very dark exceptions to the rule. The Wolf of Wall Street is by far his funniest film, a comedic journey with dramatic and vivid biopic strains, which the 71-year-old filmmaker directs with the vitality of a younger, dynamic talent. With the help of cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto, he conceives an impressive array of playful techniques and tricks: the camera zooming over cubicles and a partying sales force, the tracking shots of DiCaprio’s fourth-wall-breaking dialogue, a couple of riotous internal conversations, Quaalude-driven slow-motion, and punctuated freeze-frames. Scorsese’s unabashed liveliness in his technique here is thrilling to behold; the filmmaker has never been so appropriately unrestrained in his application of style. He further pushes the limits of his R-rating in his depiction of sexual acts and nudity, bringing into question the film’s objectification of women from start to finish. However, in embracing the subjectivity of Belfort’s story, Scorsese virtuously refuses to step back and exact a moral verdict on the misogyny and relentless bad behavior on display. As with Taxi Driver, Mean Streets, the aforementioned Goodfellas, and countless other films in his career, Scorsese aligns the viewer with a mesmerizing sociopath and involves us in their world as both spectator and participant.

Scorsese is known for gritty crime dramas and heavy explorations of flawed, dangerous characters—he’s not known for comedies, though his films The King of Comedy and After Hours represent the rare, very dark exceptions to the rule. The Wolf of Wall Street is by far his funniest film, a comedic journey with dramatic and vivid biopic strains, which the 71-year-old filmmaker directs with the vitality of a younger, dynamic talent. With the help of cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto, he conceives an impressive array of playful techniques and tricks: the camera zooming over cubicles and a partying sales force, the tracking shots of DiCaprio’s fourth-wall-breaking dialogue, a couple of riotous internal conversations, Quaalude-driven slow-motion, and punctuated freeze-frames. Scorsese’s unabashed liveliness in his technique here is thrilling to behold; the filmmaker has never been so appropriately unrestrained in his application of style. He further pushes the limits of his R-rating in his depiction of sexual acts and nudity, bringing into question the film’s objectification of women from start to finish. However, in embracing the subjectivity of Belfort’s story, Scorsese virtuously refuses to step back and exact a moral verdict on the misogyny and relentless bad behavior on display. As with Taxi Driver, Mean Streets, the aforementioned Goodfellas, and countless other films in his career, Scorsese aligns the viewer with a mesmerizing sociopath and involves us in their world as both spectator and participant.

And yet, one cannot help but question whether The Wolf of Wall Street will incite an intellectual investigation among its audiences into the reasons behind the recent financial collapse, or if it celebrates such troubling behavior through its unhinged depiction? The outcome depends on the viewer. More than half the moviegoers in my screening walked out grumbling about how the film was “disgusting” or “too much”, whereas another percentage left as if the film came with a complimentary line of cocaine at the finish, jazzed and ready to take on the world Belfort-style. Ironically enough, the majority who left worn down by the experience probably understood and had the proper reaction, whereas those young men who left shamelessly cheering about the film’s array of primitive amusements missed the irony behind Scorsese’s approach. There’s a point in the proceedings where Belfort proclaims, “Stratton Oakmon is America,” and in a scene shortly thereafter, Donnie urinates on a subpoena and incites a chant among Stratton Oakmon’s sales floor: “Fuck-you-U-S-A!” Belfort has, after all, worked the system and proved that after reaching incredible heights of wealth, the punishment for making money illegally is only a cushy white-collar prison, followed by a successful career as an author and motivational speaker.

Belfort is not a tragic figure like, say, Jay Gatsby. Earlier this year, DiCaprio played F. Scott Fitzgerald’s legendary character in Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby, an inflated film that avoided the cynical outlook of the novel in favor of CGI-enhanced period decoration. As Belfort, the second of DiCaprio’s Long Island multi-millionaire performances of 2013, there’s more effective cynicism in the film’s refusal to depict his overdue comeuppance. Although Belfort goes to jail and loses his family, his nominal punishment hardly scathes. Scorsese leaves it up to the viewer to weigh the morality of what they’ve seen, which is far braver a stroke than inventing a moralized tone in the finale. This point is beautifully articulated in one of the final scenes. After Denham has got his man, he takes the subway home and remembers a conversation with Belfort from earlier in the film, where Belfort warned that Denham’s Boy Scout behavior would land him nowhere, except taking the subway home along with every other poor sap out there. What’s better, a life of wealth, corruption, and depravity? Or the knowledge that your life is morally just, despite the daily discomforts of a middle-to-lower-class existence?

Belfort is not a tragic figure like, say, Jay Gatsby. Earlier this year, DiCaprio played F. Scott Fitzgerald’s legendary character in Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby, an inflated film that avoided the cynical outlook of the novel in favor of CGI-enhanced period decoration. As Belfort, the second of DiCaprio’s Long Island multi-millionaire performances of 2013, there’s more effective cynicism in the film’s refusal to depict his overdue comeuppance. Although Belfort goes to jail and loses his family, his nominal punishment hardly scathes. Scorsese leaves it up to the viewer to weigh the morality of what they’ve seen, which is far braver a stroke than inventing a moralized tone in the finale. This point is beautifully articulated in one of the final scenes. After Denham has got his man, he takes the subway home and remembers a conversation with Belfort from earlier in the film, where Belfort warned that Denham’s Boy Scout behavior would land him nowhere, except taking the subway home along with every other poor sap out there. What’s better, a life of wealth, corruption, and depravity? Or the knowledge that your life is morally just, despite the daily discomforts of a middle-to-lower-class existence?

Far removed from the hot-tempered salesmen in David Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross (1992) or the derivative Boiler Room (2000, also inspired by Belfort’s story), The Wolf of Wall Street is as much a riotous procession of fraternity exploits as it is a consideration-by-example of capitalism on overload. And, clocking in at three hours, it’s also Scorsese’s longest picture next to Casino, although it feels much shorter as a result of its contagious energy. Through DiCapio’s unbelievably brilliant performance and Scorsese’s directorial virtuosity, The Wolf of Wall Street becomes a comedy rooted in mortification and touches of cinematic surreality, and it’s further enhanced by its metaphoric representation of America’s financial irresponsibility. But the director refuses to temper the wild proceedings in favor of a message, and instead laces every exhausting minute with a writhing, hallucinatory, insistent, testosterone-laden buoyancy—a quality that will surely test an audience’s limits for offensive and morally distasteful material. Without passing overt judgment or becoming excessively meditative toward his subject, Scorsese depicts an intriguing and marvelously loathsome human beast in its natural setting, where the verdict on its judgment lies in the hands of its audience.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

As the season turns toward gratitude, I’m reminded how fortunate I am to have readers who return week after week to engage with Deep Focus Review’s independent film criticism. When in-depth writing about cinema grows rarer each year, your time and attention mean more than ever.

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your moviegoing—whether it’s context, insight, or simply a deeper appreciation of the art form—I invite you to consider supporting it. Your contributions help sustain the reviews and essays you read here, and they keep this space independent.

There are many ways to help: a one-time donation, joining DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or showing your support in other ways. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review