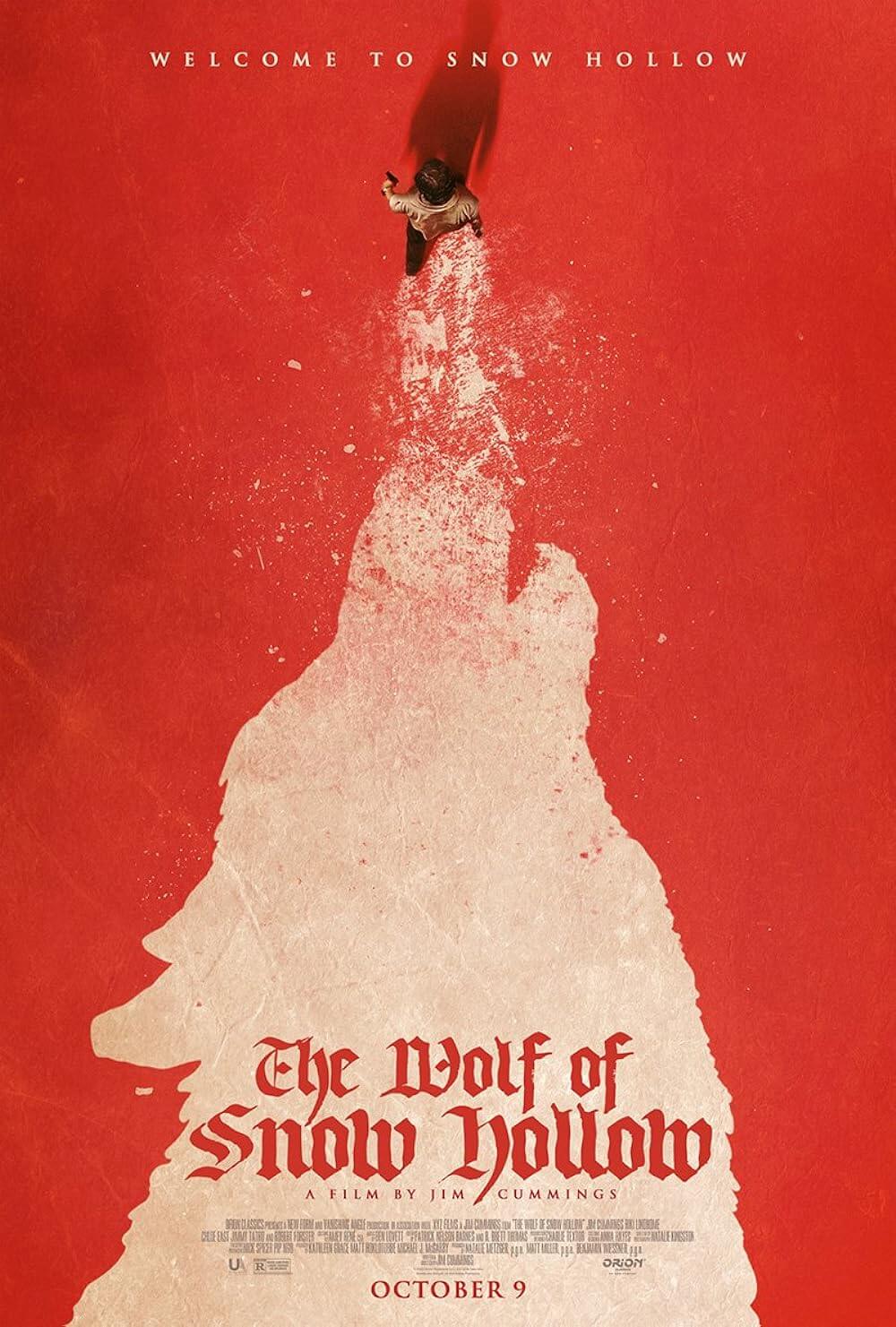

The Wolf of Snow Hollow

By Brian Eggert |

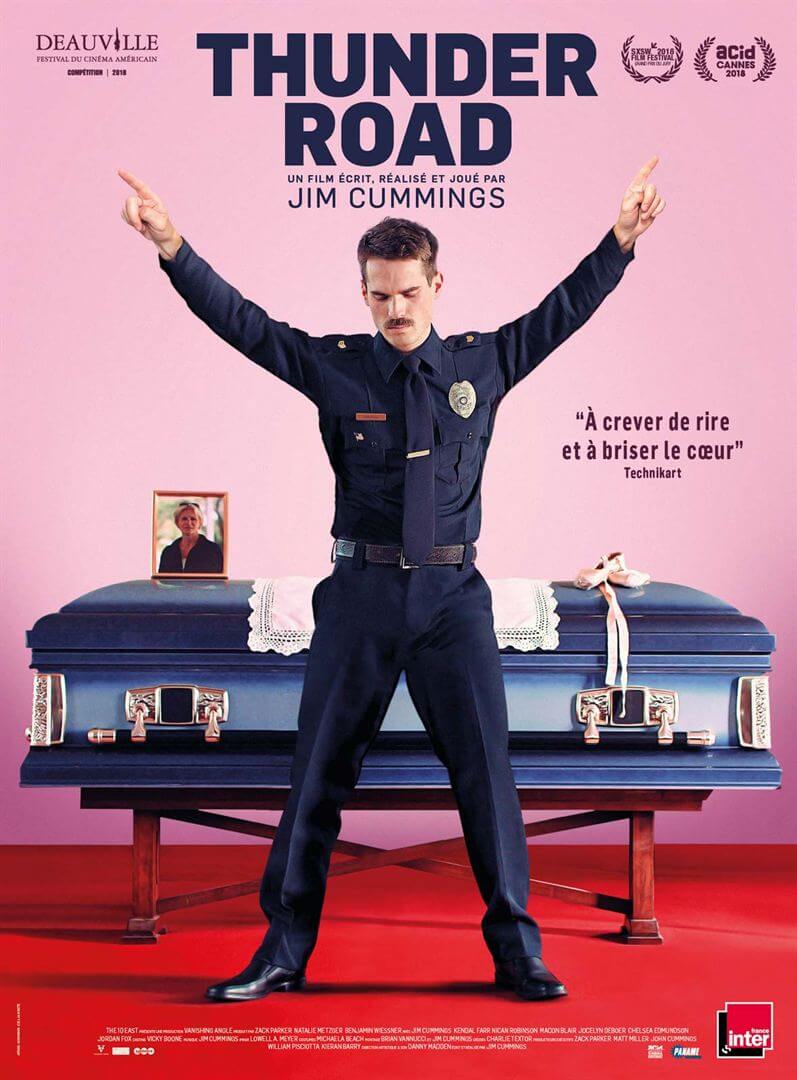

In his 2018 debut Thunder Road, writer-director Jim Cummings played Jimmy Arnaud, a cop grappling with his mother’s death. The grueling first scene features his character breaking down during the eulogy. A mixture of humiliation, open-hearted grief, and awkward humor, the scene reveals how Cummings can balance seemingly incongruous tones. He’s shattered one moment, revealing a raw story about his mother; he’s hilariously blundering the next, dancing in front of a shocked church like the self-unaware routines of Mary Katherine Gallagher. It’s painful to watch, but we watch with a cringing smile. Balancing his character’s desire to maintain a respectable policeman’s composure with his inner chaos, Cummings delivered an equally funny and wounded character in a restless performance. His second feature, The Wolf of Snow Hollow, feels like a dark twist on the same story, proving that any story worth telling is worth telling twice—especially if the second time is contained in familiar genre packaging.

Cummings plays basically the same character type as Jimmy Arnaud in The Wolf of Snow Hollow. His cop protagonist, John Marshall, once again has a rocky relationship with his former wife, once again tries to maintain a tentative relationship with an uninterested daughter, and once again faces an emotional wallop from the loss of a parent. Whereas Thunder Road proved to be a character study steeped in overwhelming stress, the follow-up takes those emotions and finds an external, thematic parallel to reflect his protagonist’s turmoil. In this case, he and other members of the Snow Hollow Sheriff’s Department, an otherwise quiet community in the snowy mountains of Utah, investigate a string of gory murders. The female victims’ bodies have been shredded, decapitated, and reproductive organs removed. Marshall and the others have never seen anything like it. What’s worse, certain details about the case point to a wolf, or perhaps a werewolf, or maybe a man in a wolf costume.

Despite being on the verge of a nervous breakdown, Marshall leads the investigation because he must. This is due in part to the ill health of his sheriff father, played by Robert Forster in his final role. His concerns about his father are compounded by the uneasy presence of his teen daughter, Jenna (Chloe East), whose rebelliousness and soon departure for college are causing Marshall anxiety. And then there are Marshall’s alcoholism and anger management issues, both of which he struggles to contain, giving way to outbursts and hotheaded insults—some hilarious, others cruel. Ultimately, he’s an insecure and fragile man whose social filters deteriorate under extreme pressure, and there’s not an aspect to Marshall’s life that isn’t tense. But from that tension emerges an ugly side that the killer’s presence amplifies. In a way, Marshall seems to know this, and catching the culprit becomes almost conditional to getting control of himself.

The Wolf of Snow Hollow is a more confidently made film than Thunder Road, which relied on Cummings’ convincing performance more than any formal elements. Natalie Kingston shoots The Wolf of Snow Hollow, and she makes the most of the setting. Shot on location in Utah, the cinematographer captures the snow-blind light of day and the atmospheric glow of artificial light at night. There are also several memorable, haunting shots of the killer, which use the scenery’s open spaces to isolating effect. What could be scarier than seeing a seven-foot-tall wolf standing on its hind legs on a deserted winter road? Elsewhere, Cummings offers a stronger group of supporting characters to augment and sympathize with his erratic hero. Riki Lindhome from Garfunkel and Oates plays another officer who has several key moments, not only in support of Marshall but in resolving the case. East, too, plays Marshall’s daughter not merely as a stressor but as a full-fledged character.

The Wolf of Snow Hollow is a more confidently made film than Thunder Road, which relied on Cummings’ convincing performance more than any formal elements. Natalie Kingston shoots The Wolf of Snow Hollow, and she makes the most of the setting. Shot on location in Utah, the cinematographer captures the snow-blind light of day and the atmospheric glow of artificial light at night. There are also several memorable, haunting shots of the killer, which use the scenery’s open spaces to isolating effect. What could be scarier than seeing a seven-foot-tall wolf standing on its hind legs on a deserted winter road? Elsewhere, Cummings offers a stronger group of supporting characters to augment and sympathize with his erratic hero. Riki Lindhome from Garfunkel and Oates plays another officer who has several key moments, not only in support of Marshall but in resolving the case. East, too, plays Marshall’s daughter not merely as a stressor but as a full-fledged character.

Cummings has progressed as a writer. Even though Marshall remains the film’s centerpiece—allowing the actor to deliver once more his high-energy deadpan and comic-tragic outbursts at coworkers and loved ones—the screenplay’s narrative thrust is a serial killer plot. The story is cleverly ambiguous throughout and refuses to identify its culprit, recalling films like The Howling (1981) and Wolfen (1981) that danced on the line between genres. Cummings uses the monster myth to symbolize his character’s anger, but he also comments on a long history of male aggression. Part of Cummings’ style is how his characters say whatever comes to mind, however gauche. That extends to his self-aware screenplay, in which Marshall openly discusses the werewolf myth as a way for cultures to explain away male violence against women. As someone who’s actively working on bettering himself, Marshall is smart enough to see the analogy at work and how it relates to his own behavior. And, eventually, he learns something from it.

Although it was shot for a mere $2 million, the modest production is a major step up from Thunder Road’s microbudget of $200,000. Cummings stretches every dollar, delivering a film with convincing practical monster effects and murder scenes, especially in the thrilling final act. What’s most impressive about The Wolf of Snow Hollow is how many moods and tonal shifts Cummings makes throughout. The viewer will find themselves laughing at his deadpan humor, gasping at the shocking violence, disquieted by Marshall’s personal lows, and moved by the resolution. It’s as though Cummings blended the comic mood of the Coen brothers’ high-stress comedy Raising Arizona (1987) within a disturbing werewolf movie, yet also managed to tell a story about losing a family member and dealing with addiction. With so many sensibilities competing with each other, The Wolf of Snow Hollow could have been a mess. Instead, it’s a confidently made pastiche that feels at once inspired and original.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review