The Wind Rises

By Brian Eggert |

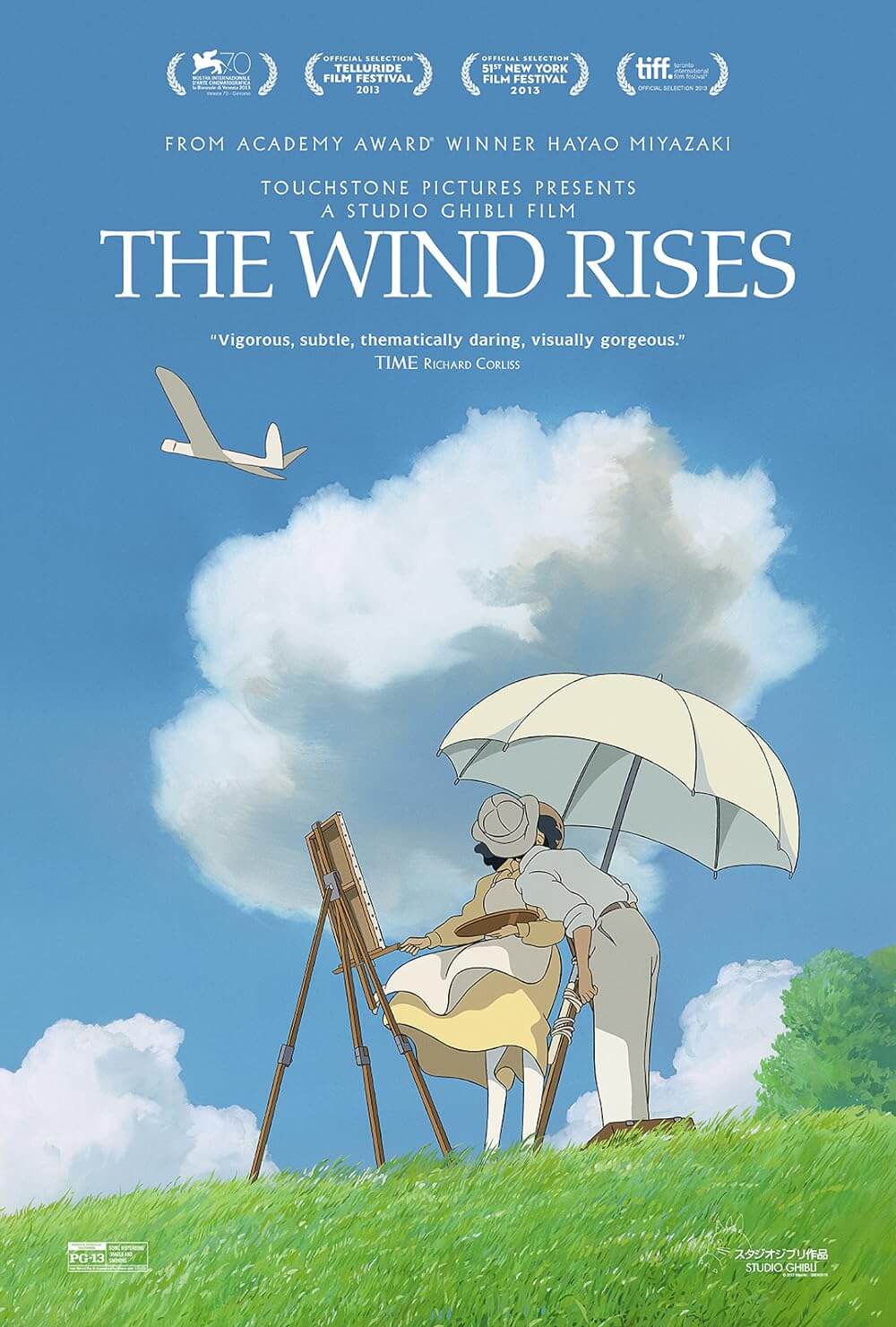

Over the last decade or more, Hayao Miyazaki, one of the few lingering animators to still work in hand-painted frames, has talked about retirement several times. At 73, the premier Japanese animator of Studio Ghibli can no longer endure those 12-hour-or-longer days attributed to his earlier efforts on My Neighbor Totoro (1988) or Princess Mononoke (1997). Miyazaki’s son Goro has taken up his father’s legacy at Studio Ghibli, directing Tales from Earthsea (2006) and his father’s script for From Up on Poppy Hill (2011). The torch has been passed, albeit not as brightly. But if there’s any film in Miyazaki’s body of work that would bid an appropriate farewell, it’s the film he claims will be his last, The Wind Rises, the writer-director’s eleventh feature in his 35-year career. In this poetic and masterful send-off, Miyazaki ruminates on themes and components that he’s explored since he began, from aviation to unforgettable dream sequences, from his pointedly humanist worldview to characters who are stricken with illness. Moreover, Miyazaki demonstrates, one last time and perhaps more potently than ever, that animation isn’t just for children.

From the outset, Miyazaki’s film is worldly and sophisticated, certainly Japanese in voice but also containing its author’s affinity for European culture. The title comes from Paul Valéry’s poem The Graveyard by the Sea: “The wind is rising,” Valéry wrote, “We must try to live!” These lines are spoken in the film by Italian aeronautical engineer Giovanni Battista Caproni in the dream of a Japanese boy, Jiro Horikoshi. Jiro and Caproni connect in a fantastically realized dreamworld where impossible airplanes come to life, and where Jiro develops his goal of becoming an aeronautical engineer like his idol. The story begins in 1918 and spans until the 1930s, sweeping through some of Japan’s most tumultuous periods in its history. As Jiro grows up, attends university, and begins working for Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, the narrative contains unforgettable and scarring moments. The Earth lets loose a horrible moan as nightmarish red fissures open during the 1923 Kanto earthquake, giving way to the unstoppable fires in Toyko that cost 140,000 lives—the abrupt editing in this sequence is scary yet brilliant. After, along with the rest of the world, the Japanese suffered through an unbearable Depression.

The way Miyazaki forms his narrative both around Jiro and also a vibrant historical context demands comparisons to the epics of David Lean. As Jiro’s ambition to design planes gives way to his love for Naoko, a terminally tubercular girl, The Wind Rises becomes a tragic and aching love story not dissimilar from Doctor Zhivago (1965), Lean’s film of Boris Pasternak’s novel about a poet who survives the 1905 Russian Revolution by his romances. Jiro and Naoko are eventually married, and, as the designer completes work on the plane for which he’ll be remembered, the film comes to a heartening close. Just as Lean composed his epics from The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) to A Passage to India (1984), individual scenes in The Wind Rises capture an epic scope yet never lose sight of their protagonist. The Kanto earthquake sequence, for example, uses a grand stage as the setpiece in which Jiro and Naoko first meet, making their introduction unforgettable. And yet, like Lean, Miyazaki’s film contains smaller moments of profound delicacies, such as a lovely sequence set around a paper airplane at a mountain getaway.

There’s also an off-putting and unexpected—and in all likelihood unintended—political controversy underneath Miyazaki’s story, in that Jiro’s real-life designs lead to the Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter plane, which bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941 and helped Japan become a global threat throughout World War II. Some have accused The Wind Rises of political and historical irresponsibility, suggesting the film somehow contains an imperialist message. One has to wonder if these critics have ever seen a Miyazaki film. Indeed, the director has always been on the side of peace, beauty, and Nature, and his films are anything but actively political. Nevertheless, The Wind Rises is unavoidably problematic for some, given how Miyazaki washes over the more unfortunate truths about Mitsubishi and how they forced Chinese and South Korean workers into slave labor. Miyazaki distances both his film and his protagonist from responsibility for how others took Jiro’s designs and mutated them into machines of war. A naïve simplicity subsists under Jiro and Miyazaki alike, their motivations pure of heart and driven by their desire to execute their craft.

Jiro hoped only to create expert flying machines, while the Miyazaki narrative signatures present in the film have been prevalent in his work since his debut. Given the dramatic touches and historical setting, not to mention a fair amount of cigarette smoking and one scene of implied marital consummation, the film has been rated PG-13. Children will be an inappropriate audience due to Miyazaki’s themes and sometimes frightening imagery; the director’s treatment also has a measured, leisurely paced style that challenged many adults who shifted in their seats during this critic’s screening. And while Miyazaki’s films have recently been imported stateside and carry the logos of Walt Disney Pictures, whose animators have used his work as inspiration over the years, the Disney castle is conspicuously absent before The Wind Rises (in its place is the logo for Touchstone Pictures, one of Disney’s many distribution labels). Still, Disney assembled a strong voice cast for the English dub, among them Joseph Gordon-Levitt as Jiro, Emily Blunt as Naoko, Stanley Tucci as Caproni, and even Werner Herzog as a spritely and mysterious German fellow.

The Wind Rises is a fascinating last film for Hayao Miyazaki and a swan song that seems to encapsulate the animator’s recurrent autobiographical strains in largely real-world terms: Miyazaki grew up around his father’s airplane parts company and, in his films, has shown a fascination with elaborate flying machines (evidenced in Porco Rosso and Castle in the Sky), while like Naoko his mother suffered from tuberculosis (also referenced in My Neighbor Totoro). Savoring the film requires the viewer to plunge themselves into Miyazaki’s frame of mind, both as an artist and a man at the end of his career. But on a much simpler level, it requires that its audience see Miyazaki’s hand-drawn animation as art, appreciate his painterly backgrounds and stylized human figures, immerse themselves in the scope of his love story, and, finally, to recognize the pure beauty of something so simple as a flying machine. Those who take issue with the film’s agenda, if such an ugly word can be applied to this film, need only reflect on the film’s inspiration. Miyazaki read a quote by the actual Horikoshi about his airplane designs: “All I wanted to do was to make something beautiful.”

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review