The Whale

By Brian Eggert |

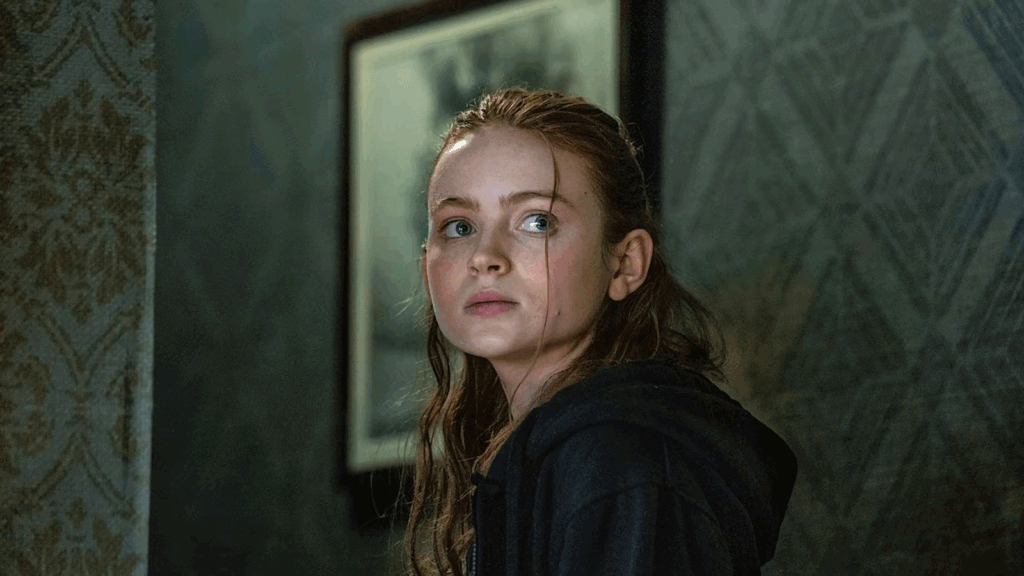

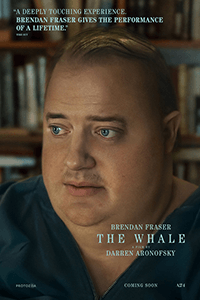

Darren Aronofsky’s The Whale features Brendan Fraser as Charlie, a broken man whose grief and fatalism have caused him to binge-eat his feelings, leaving him massively obese. Believing he has only a few days before he dies from congestive heart failure, Charlie attempts to find closure with his estranged daughter Ellie, played by Sadie Sink. The screenplay, written by Samuel D. Hunter, based on his play, is perfectly attuned to Aronofsky’s sensibilities, starting with its barefaced symbolism. From the pointed title to the larger-than-life performances to the story’s open discussion of literary themes in Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, the material feels suited for the stage, less so for film. Not only does the feature take place (mostly) in a single location like a chamber piece, but the performances and dramaturgy have been calibrated to reach the back row. Fortunately, Fraser gives a memorable, award-baiting performance in the lead role, acting from behind a digitally augmented suit that mostly renders a convincing effect. But it’s the director’s tendency to underline every point, every symbolic connection, and make them unmistakable for the viewer that leaves The Whale feeling like a lofty yet tedious exercise.

Aronofsky is no stranger to obsessed characters who take on immoderate lifestyles; he has built a career around them. His debut feature, Pi (1998), follows a paranoid theorist whose ideas about a mathematical equation lead to conspiracies and self-destruction. In many ways, every subsequent Aronofsky feature has been a variation on Pi’s structure of fixation and implosion, whether they’re about drug addiction (Requiem for a Dream, 2000), the pursuit of everlasting life (The Fountain, 2006), an athlete’s punishing commitment to his performative sport (The Wrestler, 2008), or a dancer’s ruinous devotion to her craft (Black Swan, 2010). More recently, Aronofsky has put his characters’ singular drives into religious allegories, such as Noah (2014) and mother! (2017), both overwrought in their symbolism and excessive style. In each case, he delights in characters who have extreme perspectives, and their psychological torment is tantamount to their physical suffering—a dynamic that Aronofsky often manifests in gristly, unflinching, and often blatantly obvious ways.

So it’s not surprising that the auteur was drawn to Hunter’s play and its account of Charlie, an online English teacher who overeats out of depression after losing his partner years earlier. Either stuck on his couch or, later, in an extra-wide wheelchair, Charlie receives daily visits at his apartment from his nurse friend, Liz (Hong Chau). She’s an enabler who, despite loving her friend, continues to bring Charlie groceries and passively monitor his decline. Others enter the picture, too. The Whale opens with a knock on Charlie’s door at an awkward moment, prompting heart palpitations that leave him sweaty and clutching his chest. A missionary named Thomas (Ty Simpkins) has come to spread the word of a culty-sounding church, New Life, but he finds Charlie near death. In the throes of chest pain, Charlie demands that Thomas read aloud from an essay about Moby Dick, which, when recited, calms Charlie down. Once the episode passes, Charlie realizes his end is nigh, so he resolves to call Ellie for the first time in years.

The film unfolds almost entirely inside Charlie’s apartment, framed in the claustrophobic Academy ratio—the go-to tactic for today’s filmmakers to evoke spatial and existential alienation. Cinematographer Matthew Libatique’s fluid maneuvers around the apartment never call attention to themselves, but his color palette appears grimy and green, somewhere between putrid and sweaty. Outside, in the rural Idaho surroundings, the omnipresent overcast skies and rain aren’t much cheerier. The apartment’s dour setting is accented by liters of soda and hidden stores of food that Charlie consumes like he’s actively injecting poison into his body, trying to end his pain through his compulsive eating. Beneath prosthetics that make him appear around 600 lbs., Fraser’s large, expressive eyes and sensitive voice bear a vague resemblance to his square-jawed presence in Encino Man (1992) and The Mummy (1999). But Fraser has been open about how Hollywood has chewed him up and spit him out, his aging, and his pain. Occasionally the effect looks like a digital trick, but the actor mostly disappears into the role because he’s so incredibly genuine.

Fraser’s performance buoys the entire film, with Chau’s sharp turn giving the experience some convincing dimension. Later in the film, Samantha Morton makes an appearance as Charlie’s ex-wife, and it’s a scene-stealing role, similar to her part in this year’s She Said. Less convincing is Sink’s Ellie, who’s a cartoonishly angry teen and downright awful to the point of ruining any goodwill toward the character. Ellie calls her father “disgusting,” mocks his sexuality as a gay man, and finally tells him to “Just fucking die already!” Not even the melodrama’s last-minute attempt at redemption can make her tolerable. The film requires the viewer to extend a level of forgiveness to Ellie that can only be called Christlike, which, of course, Charlie can achieve, given his profound sadness and guilt. Charlie’s enduring optimism, buttressed by Fraser’s wounded presence, attempts to counteract the punishing and mostly miserabilist quality of the film. Everyone is “amazing” (his favorite adjective), and people are “incapable of not caring.” Charlie’s optimism resides in his big heart, which may be too vast to survive the emptiness left over when his partner died. That void cannot be filled, no matter how much binging he does.

The problem with The Whale is not the performances; it’s Aronofsky’s handling of the material, and further, the material itself. The director has been here before, with better results. His best film, The Wrestler, also centered on a character who, afflicted by a failing body and grim prognosis, reconnects with the daughter he abandoned. But where that film found Aronofsky embracing earthy realism, The Whale sees him indulging in a gluttonous degree of symbolism. Given the material’s source, a certain amount of staginess and overstatement is to be expected. But it’s not merely that Hunter’s script nods to Melville’s book and biblical imagery in the text; it’s also in how Charlie demands honesty from his essay students but cannot be honest with himself. And it’s how Aronofsky plays up these aspects throughout, making the film more about the literary and symbolic connections than the emotional context. Most deflating to the drama is how the bookend scenes both involve someone standing in Charlie’s doorway, reading from the same essay. The first time, it saves his life; the second time, it saves his soul. The parallelism might work on the stage, but here, it feels overembellished and spoils the last scene.

More than films such as The Fountain or mother!—the director’s two titles with the most egregious runaway symbolism—The Whale finds Aronofsky giving his audience room to share a space with his characters. Cloistered and grubby as that space may be, the film contains no end of pathos and even overextends itself in that department. Indeed, the third act’s resolutions and speeches become awfully theatrical, naggingly so, and their impact is only spared from condemnation by Fraser selling them as best he can. He has rarely been so good outside of Gods and Monsters (1998) and The Quiet American (2002). But not even Fraser’s much-lauded, doubtlessly Oscar-worthy performance—and those of his excellent costars—can rescue the film from Aronofsky’s fussy and conspicuous direction of this agonizing story.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review