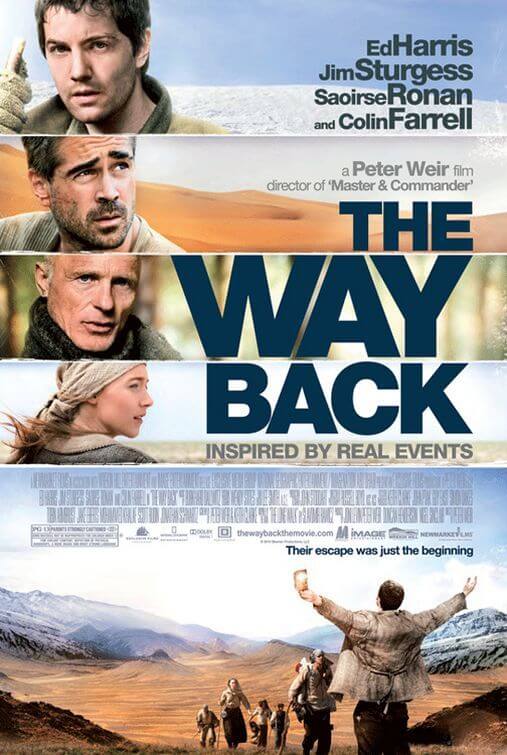

The Way Back

By Brian Eggert |

Peter Weir’s The Way Back tells an adventure story in epic fashion, though comparisons to the work of David Lean (Lawrence of Arabia) are greatly exaggerated. Based on the factually debunked novel The Long Walk by Slawomir Rawicz, the film uses Rawicz’s story as a launching point from which it vastly diverts. It follows Janusz (a character based on Rawicz), a Polish lieutenant imprisoned in a Siberian gulag during World War II. He and several fellow inmates make a perilous escape, slogging through frozen mountains and forests in Siberia, across the plains of Mongolia, over the dunes of the Gobi desert, and beyond the Himalayas to safety in India. In all, the story, its facts widely disputed, covers some 4,000 miles of unforgiving terrain, and Weir makes his audience feel almost every step.

Weir and his co-writer Keith Clarke put the audience through a grueling, more-than-two-hour experience of walking—just walking—as they dwell on the lengths that the film’s fictionalized characters will go to be free men. In the opening Gulag scenes, a prison warden announces (in a speech recalling Lean’s The Bridge on the River Kwai) that the prison itself will not prevent escape, but the merciless landscape surrounding the prison will. Soon an unimpressive prison break sequence leaves a handful of men to contend with the elements. Weir and Clarke resolve to make a film about pure survival, and nothing more. Indeed, the audience doesn’t learn why the compelled Janusz (Jim Sturgess) simply must escape until twenty minutes before the film is over, whereas knowing his motivations earlier would have perhaps given the film needed emotional depth. Instead, there are no major character arcs to cling to, few deeply human interactions, rather just a tale of Human vs. Nature that features gorgeous scenery.

The cast is made up of impressive performers, who have little to do, aside from looking frostbitten, desperately hungry, deathly parched, or otherwise dead-tired. Ed Harris plays an American prisoner named Smith; Colin Farrell plays a Russian criminal, a most interesting character who disappears mid-way into the journey; and Saoirse Ronan plays a Polish refugee, another character who Weir and Clarke dispense of too early. The most unfortunate bit of casting is Sturgess, the leading man whose boyish looks never capture the starvation or desperation that the sunken visages of Harris or Ronan provide. Meanwhile, Farrell’s role and an appearance by Mark Strong have more fervor in their limited screen time than the rest of the cast combined.

The presentation contains little else aside from physical hardships, which are rendered with impressive attention to authenticity. However, only in the final scenes do we learn that Janusz has long yearned to get home to his wife, to relieve her of the guilt she must feel after being tortured and forced to testify against her husband. But even after making the voyage to India, the lasting communist presence in Poland will not allow him to return home. There’s a silly montage of newsreel footage detailing the fall of communism over the next few decades set against Janusz’s ragged boots marching across time. The sentimental reunion in the finale has almost no emotional bearing with which to affect the audience, leaving the moment flat and the conclusion to a long plod empty.

Weir has dealt with scenic adventures before on Gallipoli, The Mosquito Coast, and most recently Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World, but never have his films felt so lacking in character or emotion. Weir and Clarke seem so swept away by the astounding concept of the story that they forget to attach a dramatic resonance to it, and the personal dramas that do occur (though laden with eye-rolling Christian symbolism) feel diminutive next to the film’s vistas. Perhaps Weir should have taken a cue from the aforementioned Lean, or Werner Herzog, both filmmakers who know that characters have to be larger than his panoramas to provide an even experience.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review