The Wandering Earth

By Brian Eggert |

Hollywood knows that a strong appeal to the Chinese market is more gainful than domestic box-office receipts alone. The studios have exploited this fact by introducing Chinese characters and locations into major releases, sometimes, as in the case of certain Marvel titles, going so far as to shoot entire sequences in China that are omitted from the Western version of the film. Perhaps it’s no surprise that American studios aren’t as willing to import foreign titles as they are to modifying their export products to appease foreign markets. With few exceptions, films made outside of the U.S. rarely perform well domestically. Even so, China has sought to partner with Hollywood interests to make features like The Great Wall (2016), an epic war fantasy starring Matt Damon alongside a predominantly Chinese cast. It bombed in the states but made almost $335 million worldwide. As China continues to develop a blockbuster film industry of its own, U.S. audiences can expect more Chinese imports to hit theaters and, increasingly, they will begin to resemble proven Hollywood formulas.

The Wandering Earth is such a movie. It isn’t the most expensive Chinese production of all time, but few have so closely resembled a Western blockbuster. Each entry in franchises such as Monster Hunt and The Monkey King cost more; however, their appeal to Western audiences on a massive scope has been virtually untested in a large-format release model. Many of them involve China’s intricate history and mythology, much of which would be lost on the average American. And so, distributors and exhibitors in the U.S. are taking baby steps to import Chinese movies. But with production costs upwards of $50 million, The Wandering Earth feels like something designed and calibrated for international appeal. It’s an outlandish, world-saving scenario filled with futuristic technology, messages of hope, and a familiar popcorn-munching setup. Regardless, the movie has received little promotion in the U.S., aside from a limited stint in AMC theaters and an eventual release on Netflix.

Director Frant Gwo opens his movie with a breakneck prologue, which quickly explains that the Sun is expanding and, within a few hundred years, it will engulf the Earth. The newly formed United Earth Government concocts a wild idea to ensure the survival of the human race: They’ll affix some 10,000 engines to the planet, turning Earth into a mobile shuttle that will travel over 4 light-years away to a nearby star—a journey that will take thousands of years. But once these powerful engines are turned on, “mega-tsunamis” will flood the planet’s surface. And so, the governments resolve to build vast underground cities as living space for half of the world’s population, having won their spot below in a lottery. The other half is doomed to drown on the surface; at the very least, they’ll freeze in the sub-zero temperatures once the planet begins to move away from the Sun. Not much time is spent on how their plan involves killing half of the population to save the other half. Nor does the screenplay, credited to seven writers, explore why the human race dumps so much time and effort into building underground cities instead of space shuttles.

Then again, it’s best not to think about The Wandering Earth’s preposterousness, if that’s an option for you. It wasn’t for this critic. How does one ignore the elementary school science that has been overlooked by the screenplay? Consider how moving the Earth away from the Sun causes the planet to freeze, which in turn prevents the creation of necessary gasses to form, therein eliminating the atmosphere. Moreover, why bother moving an entire planet if you’ve obliterated an atmosphere that’s taken hundreds of millions of years to form? In any case, the ridiculous proceedings make the usual brand of iffy science found in disaster movies look downright scholarly by comparison.

Then again, it’s best not to think about The Wandering Earth’s preposterousness, if that’s an option for you. It wasn’t for this critic. How does one ignore the elementary school science that has been overlooked by the screenplay? Consider how moving the Earth away from the Sun causes the planet to freeze, which in turn prevents the creation of necessary gasses to form, therein eliminating the atmosphere. Moreover, why bother moving an entire planet if you’ve obliterated an atmosphere that’s taken hundreds of millions of years to form? In any case, the ridiculous proceedings make the usual brand of iffy science found in disaster movies look downright scholarly by comparison.

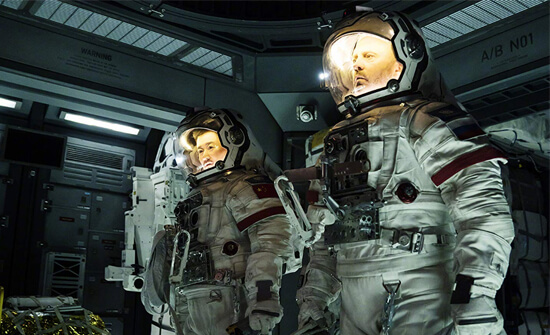

The screen story picks up 17 years after the start of the “Wandering Earth Project” gets underway, as the rocket-powered Earth approaches the gas giant Jupiter. Somehow, no one realized that Jupiter’s gravity would pose a problem for Earth’s journey—the entire mission is placed into jeopardy when gravity threatens to cause a collision between the two planets. In a space station traveling ahead of the planet, Liu Peiqiang (Wu Jing) scrambles to help those on the surface, but he’s thwarted by MOSS, the station’s eerie, red-eyed computer program. On the surface, Liu Peiqiang’s father (Ng Man-tat) joins a last-ditch rescue mission to reignite some failed engines with something called a “lighter core.” Liu Peiqiang’s son Liu Qi (Qu Chuxiao), joined by his adopted sister Han Duoduo (Zhao Jinmai), is the hero on the surface, organizing an ensemble of scientists and military types to resolve one disaster after another—culminating in the Hangzhou-set climax.

Based on a story by author Cixin Liut, the movie is an experience that can only be described by comparing it to similar Hollywood movies. The laundry list of similar titles includes just about every science fiction and disaster movie made in the last 30 years. Fans of Michael Bay and Roland Emmerich will feel right at home. You’ll think of Armageddon when the characters come to the most impossible, absurd, laugh-in-the-face-of-science solution imaginable to solve their planetary conundrum. But Emmerich’s influence is greater: The brief scenes that show the world preparing for disaster with a horrific lottery prior to launch recall 2012. The frozen Earth scenes bring to mind The Day After Tomorrow. The scenes of Shanghai skyscrapers toppling over are pure Emmerich as well. You’ll even think of Dean Devlin, Emmerich’s former partner, whose Geostorm is only slightly less absurd than The Wandering Earth. Elsewhere, the space station sequences borrow from Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity, whereas below the Earth we think of that middling effort The Core. And most obviously, the homicidal MOSS is a cheap knock-off of HAL 9000 from 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Given that it’s drawing from well-established material, the script is filled with clichés abound, making it indistinguishable from a dozen poorly written Hollywood blockbusters. There are stock character types, from the comic relief Tim (Mike Sui), who has an eyebrow-raising statutory rape charge, to Li Yiyi (Zhang Yichi), the resident techie whiz-kid. Our heroes must make last-minute rescues, breathless leaps across expansive chasms, outrun planetary fireballs, and give a labored thumbs-up before dying. And there’s a heavy-handed theme about the importance of hope in dire situations that materializes in banal statements such as “hope is our only direction” or “hope is like a precious diamond.” Elsewhere, when one character armed with a body-mounted minigun (à la Jesse Ventura from Predator) loses hope, he resolves to bellow out and unload countless rounds in Jupiter’s general direction—an unintentionally funny choice. It’s all sort of admirable in its goofiness, but there’s not much for the viewer by way of character development. However, whenever Frant Gwo wants to tug on our heartstrings, he knows to cut to a crying Zhao Jinmai and turn the sappy score to eleven.

Given that it’s drawing from well-established material, the script is filled with clichés abound, making it indistinguishable from a dozen poorly written Hollywood blockbusters. There are stock character types, from the comic relief Tim (Mike Sui), who has an eyebrow-raising statutory rape charge, to Li Yiyi (Zhang Yichi), the resident techie whiz-kid. Our heroes must make last-minute rescues, breathless leaps across expansive chasms, outrun planetary fireballs, and give a labored thumbs-up before dying. And there’s a heavy-handed theme about the importance of hope in dire situations that materializes in banal statements such as “hope is our only direction” or “hope is like a precious diamond.” Elsewhere, when one character armed with a body-mounted minigun (à la Jesse Ventura from Predator) loses hope, he resolves to bellow out and unload countless rounds in Jupiter’s general direction—an unintentionally funny choice. It’s all sort of admirable in its goofiness, but there’s not much for the viewer by way of character development. However, whenever Frant Gwo wants to tug on our heartstrings, he knows to cut to a crying Zhao Jinmai and turn the sappy score to eleven.

Although much has been said about the budget and the movie’s potential appeal to Western viewers, this isn’t a spared-no-expense production by the state-owned China Film Group Corporation. Scenes on the Earth’s frozen surface, especially those involving the surface vehicles, look cartoonish or like a video game. Although the interstellar shots that show the Earth approaching Jupiter have a sublime beauty to them, The Wandering Earth cannot help but look like a B-grade effort after a film like, say, Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar. Indeed, the movie follows a rather outmoded model of large-scale disaster movies that have fallen out of fashion in Hollywood. Even worse, the frantic editing by Cheung Ka-fai renders the otherwise sharp camerawork by Michael Liu difficult to follow in high-tension sequences, especially in the climax. Worst of all, the subtitles often confuse verb tenses and misuse articles, making one wonder why, if the production was so monumental, the financiers didn’t invest in a better translation. This results in several unintentionally funny moments that occur from obviously mistranslated lines, such as one character saying to another, “You are a mishap.”

It’s curious that The Wandering Earth seeks to appeal to U.S. audiences by taking the form of such an out-there movie. Then again, most big-budget Hollywood tentpoles are ridiculous and stupid, and so it makes sense that China’s version of one would be ridiculous and stupid as well. The most compelling aspects of the movie, ironically enough, reside in the differences between Chinese and Western cultures—the specifics of Chinese identity and social values distinguish themselves in this familiar setting. So while the sci-fi disaster movie plotting and production values resemble the aforementioned blockbusters, it’s fascinating to see a commonplace scenario with cultural flourishes unique to China. Nevertheless, The Wandering Earth doesn’t break the mold; it jealously conforms to the extent that its sole novelty is the basic concept of moving Earth through space with thousands of rockets. Inspired though this idea may be, it’s also frustratingly dumb, a quality that spoils its potential fun with underwritten characters and no end of ludicrous plot developments.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review