The Walk

By Brian Eggert |

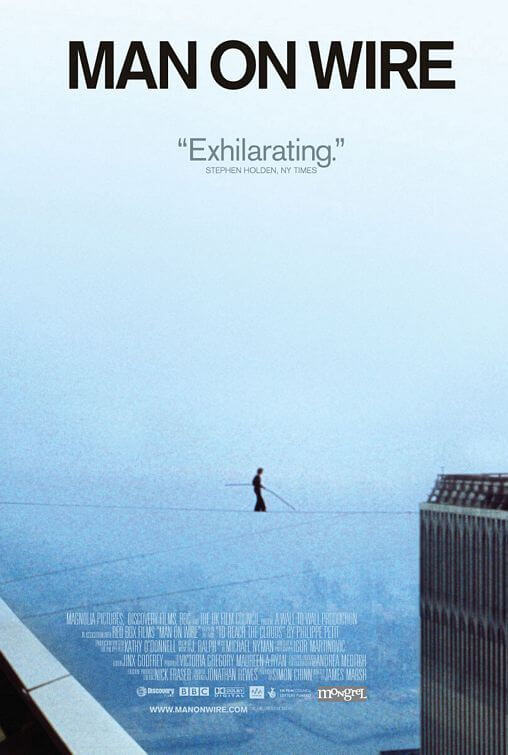

On the morning of August 7, 1974, wirewalker Philippe Petit appeared 1,350 feet off the ground, balancing on a 450-pound wire he had illegally extended between the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. Ignoring the mounting police presence on either building, Petit passed along the wire’s 140 feet length between the towers eight times over the course of 45 minutes, while below crowds gathered and watched in wonder. His brand of unauthorized performance art had already been renowned in walks between the Notre Dame Cathedral towers and Sydney Harbour Bridge towers in previous years. But nothing he’d accomplished before or since would compare to this. Petit’s exploit was covered by James Marsh’s brilliant and thrilling 2008 documentary Man on Wire, which featured actual footage and participants commenting on the unauthorized and highly illegal event, largely supported by the contagious energy of Petit’s retelling. Robert Zemeckis (Forest Gump, Flight) has turned this story into a film called The Walk, using plenty of less-thrilling computer-generated images, in-your-face 3D effects, and Joseph Gordon-Levitt in a peculiar performance as Petit.

Zemeckis delivers a true-to-form Hollywood adaptation of a real-life marvel, complete with a big studio score by Alan Silvestri, top-notch production design by Naomi Shohan, and sharp lensing by Dariusz Wolski. It’s also about as subtle as a slap in the face. The Walk‘s most off-putting aspect is how Gordon-Levitt’s Petit tells his story by breaking the Fourth Wall and narrating throughout. He appears standing on the walkway of the Statue of Liberty’s torch, an area closed to the public since Germans sabotaged a nearby munitions depot in World War I and the resulting explosion caused the statue structural damage. In the background are the digitally rendered World Trade Center towers, glimmering in sunlight or, depending on the mood of the story at a particular point, might seem to stand out amid fog or an approaching storm. And yet, we have already seen Petit himself tell his story in Man on Wire. Why Zemeckis and his co-writer Christopher Browne chose to tell the story in the same manner as Marsh’s film remains curious. Granted, their source material is Petit’s book To Reach the Clouds, but a dramatic reenactment would have been preferred to this odd stage.

Much of the (rather annoying) first hour or more is spent in Paris, telling of Petit’s early life, how he learns the trade of wire walking from old pro Papa Rudy (Ben Kingsley), how he falls for street musician Annie (orb-eyed Charlotte Le Bon), and how he enlists devoted friends in his plan: photographer Jean-Louis (Clement Sibony) and acrophobic math teacher Jeff (Cesar Domboy). He calls this plan “the coup” and strategizes to carry out his artistic showcase like a master thief preparing for the proverbial heist of the century. He calls his research “spy work” and the scheme requires infiltrating tower security, knowing timelines, security policies, building specifications, and countless other details. His so-called “accomplices” endure his crazed obsession with the feat, no matter how dangerous; they endure his erratic behavior because they can see he’s also an inspired genius. In Marsh’s doc, the planning stages were among the most exciting parts of the story. In Zemeckis’ usually accomplished hands, the build-up feels like padding until the main event.

Much of what doesn’t work about The Walk resides in the aforementioned framing device and the portrayal of its host. In most other arenas, Joseph Gordon-Levitt is a fine actor whose performances are often admirable. Here, he’s under a distracting dark red wig and blue color contacts. He donned a similar getup for Looper (2012), but that was to resemble the older version of his character, played by Bruce Willis. Here, there’s no archival footage of the actual Petit and therefore no reason the audience wouldn’t have accepted the actor’s normal appearance as the character (at any rate, Petit’s actual hair color was much lighter). Moreover, Petit’s natural flamboyance, one of the most engaging aspects about Marsh’s doc, is strange in Gordon-Levitt’s hands. In Man on Wire, Petit spoke with grandiosity and used wild hand gestures. He was animated and fascinating. No matter how fine an actor, there’s a difference between watching a whimsical Frenchman tell his story and watching an American actor pretend to be a whimsical Frenchman telling his story. Sadly, Gordon-Levitt never disappears into his role.

Zemeckis tries to match his protagonist’s flamboyance with equal measures of visual bravado. To be sure, there are breathtaking moments when the actual walk occurs from 110 stories up, and we see the entire cityscape in the background. The sequence is entirely worth enduring the rest of the picture. However, the kitschy application of CGI imagery spoils much of the virtuosity with distracting, and downright silly, visual flourishes. Meant to be screened in IMAX 3D (which is how this critic viewed it), The Walk boasts annoying moments meant to highlight the 3D. Everything from hard candy to arrows to falling wires fly at the viewer. The worst among them is a bad omen in the form of a CGI seagull. These flourishes lessen the integrity of the film and visual device, as 3D is best used to show a receding depth of field (see its use in the recent Everest). When random objects pop out at you, it cheapens the experience; and without 3D, since most viewers will see this film in 2D or in their living rooms, these touches seem nothing short of ineffective and unintentionally laughable.

Petit’s incredible artistic coup enchanted New Yorkers and even endeared them to the newly erected Twin Towers, which before were considered a bland eyesore on the beloved skyline. And so, The Walk contains a post-9/11 ache. From that perspective, Zemeckis has jealously made this film more as a remembrance for Americans than a celebration of Petit’s artistry. Notice how the script avoids Petit’s oft-used description of the buildings as “my towers”, one of the man’s most charming qualities from Man on Wire, as only he had conquered them. Zemeckis separates the audience from the profundity of what Petit accomplished by allowing his visual components to overshadow the inconceivable real-life story. What a shame. The most incredible aspect of The Walk comes from a critical perspective, in that two films could tell the same story with such divergent results. The documentary leaves you breathless and enchanted by the tale and main character; the fictional account leaves you irritated by the protagonist and underwhelmed by an otherwise unparalleled act of performance art.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review