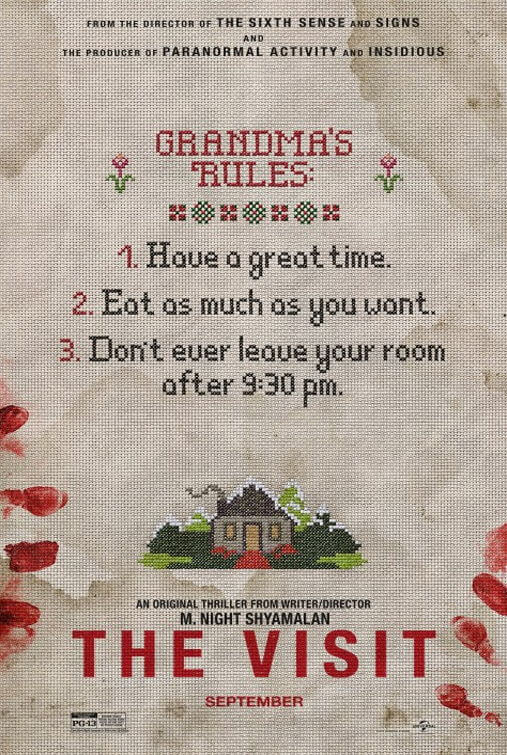

The Visit

By Brian Eggert |

“You have to laugh to keep the deep darkies in a cave,” says Nana, just before she tries to suffocate herself with a babushka. In M. Night Shyamalan’s The Visit, something’s wrong with two very creepy grandparents, dubbed Nana and Pop Pop. It’s an effective setup for this low-budget horror yarn from Blumhouse Productions, which seems to release a new movie every few weeks as of late. Shyamalan has resolved to exploit today’s popular, cheap found-footage shockers after a string of personal creative and commercial disappointments, beginning with The Village in 2004, followed by Lady in the Water (2006), The Happening (2008), The Last Airbender (2010), and After Earth (2013). His latest doesn’t improve his track record much, but it will undoubtedly earn a profit on its slim budget of $5 million.

The Visit creates ample tension early in the film. 15-year-old Becca (Olivia DeJonge), an aspiring documentarian, vows to record her trip with her 13-year-old brother, Tyler (Ed Oxenbould), an aspiring rapper, to meet their grandparents for the first time. Their mother (Kathryn Hahn), estranged from her parents, concedes when her parents ask to meet their grandkids, whom they’ve never met, even though she hasn’t seen her parents in 15 years. When Becca and Tyler arrive by train, Nana (Deanna Dunagan) and Pop Pop (Peter McRobbie) seem nice enough, if quirky in a small-town sort of way. Soon, the children discover major warning signs on their grandparents’ farm. Nana scratches the walls at night. Pop Pop is caught with a gun in his mouth. Nana and Pop Pop volunteer as counselors at the local hospital, and their coworkers show up at the house, always when Nana and Pop Pop are gone, wondering why they haven’t shown up lately. Whatever their malfunction ends up being, it’s a gradual build finding out.

Complete with a rather clever and disturbing Shyamalan-style twist, The Visit at least keeps us guessing about whatever’s going on. And the fake-outs leave us to wonder… Are they ghosts? Monsters? Aliens? What will the twist be? Witches, perhaps? Nana asks Becca to get in the oven to thoroughly clean it, recalling Hansel & Gretel lore. Ridiculously, Becca abides. (NOTE: Kids, if anyone, grandma or otherwise, asks you to get in an oven to clean it, direct them to the oven’s “clean” setting. Do not get in.) Maybe Nana and Pop Pop are werewolves—there are several shots of the moon, after all. Unfortunately, this 90-minute slow-burner waits until fifteen minutes before the end credits to reveal that twist, long after the suspense is gone, and we’ve stopped caring. Shyamalan forgets why his audience would see a movie like this. They want effective jump-scares and things that leap out in the dark. Of course, you get such clichés in small doses. But Shyamalan’s more interested in the ham-fisted, obvious relationships between the family members.

Per usual, Shyamalan overwrites his characters. Becca is a future auteur extraordinaire who drops filmmaking terms like “dénouement” and declares her high “cinematic standards”. Her pretentious dialogue shows Shyamalan demonstrating his knowledge of filmmaking craft, and through her, puts forth his own genius. It’s not as egregious as his crimes with Lady in the Water, where he cast himself as a writer so brilliant that his words save the world, but it’s pretty darn self-important. Likewise, he overestimates Tyler’s charm. While effective in releasing tension with amusing comic relief after suspenseful moments, we hardly want to watch Tyler rap over the end credits. Shyamalan ties his characters up in a big emotional bow, complete with obvious daddy issues to work through, which of course, are resolved in the climactic scene. If there’s one thing you can bet on in any Shyamalan film, it’s an obvious metaphor. Here, he packs on the schmaltz in the overly emotional finale, where he clearly believes his audience should have the same emotional breakthrough as his characters, except we aren’t.

Kudos to Shyamalan for trying to raise the bar. He changes the usual found-footage schema into a faux documentary and avoids many of the subgenre’s tropes while retaining the visual style. But his heavy-handedness in both his character design and plotting wears on the viewer. Although Shyamalan attempts to elevate the low-brow sub-genre with family melodrama, he creates a project that feels all the more artificial for its failure to make us care—the same can be said for any number of Blumhouse titles (Insidious, Paranormal Activity, etc.), which is strange since they joined the project after filming had wrapped. When Mom declares, “Don’t hold on to anger,” and hugs Becca in the last teary moments, the viewer can’t do much else but shrug or roll one’s eyes. It’s all a very transparent metaphor for family reconciliation and what happens when your old wounds don’t heal. Except, five minutes earlier Pop Pop shoved his soiled diaper in Tyler’s face, so it’s quite difficult to think about anything else just then.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review