The Truth

By Brian Eggert |

Naturally, The Truth (La vérité) was bound to feel like an anomaly in the career of Japanese filmmaker Hirokazu Kore-eda. It’s the first film by the writer-director shot in a language and country not his own. It features a cast of mostly French actors and one North American, most of them well-known performers on the international film scene. Given these alternations to Kore-eda’s usual pictures that revolve around the Japanese home, whether it’s the middle-class family in Still Walking (2009) or the makeshift abode created by an unrelated band of thieves in his Palme d’Or-winning Shoplifters (2018), his new film seems like a significant departure. But it’s an outlier in a way that recalls Iranian director Ashgar Farhadi’s detour into a Spanish-language thriller in last year’s Everybody Knows, in that the glaring deviations prove mostly superficial. Though Kore-eda has changed the location and language of his characters, his thematic interest in family dynamics remains firmly intact.

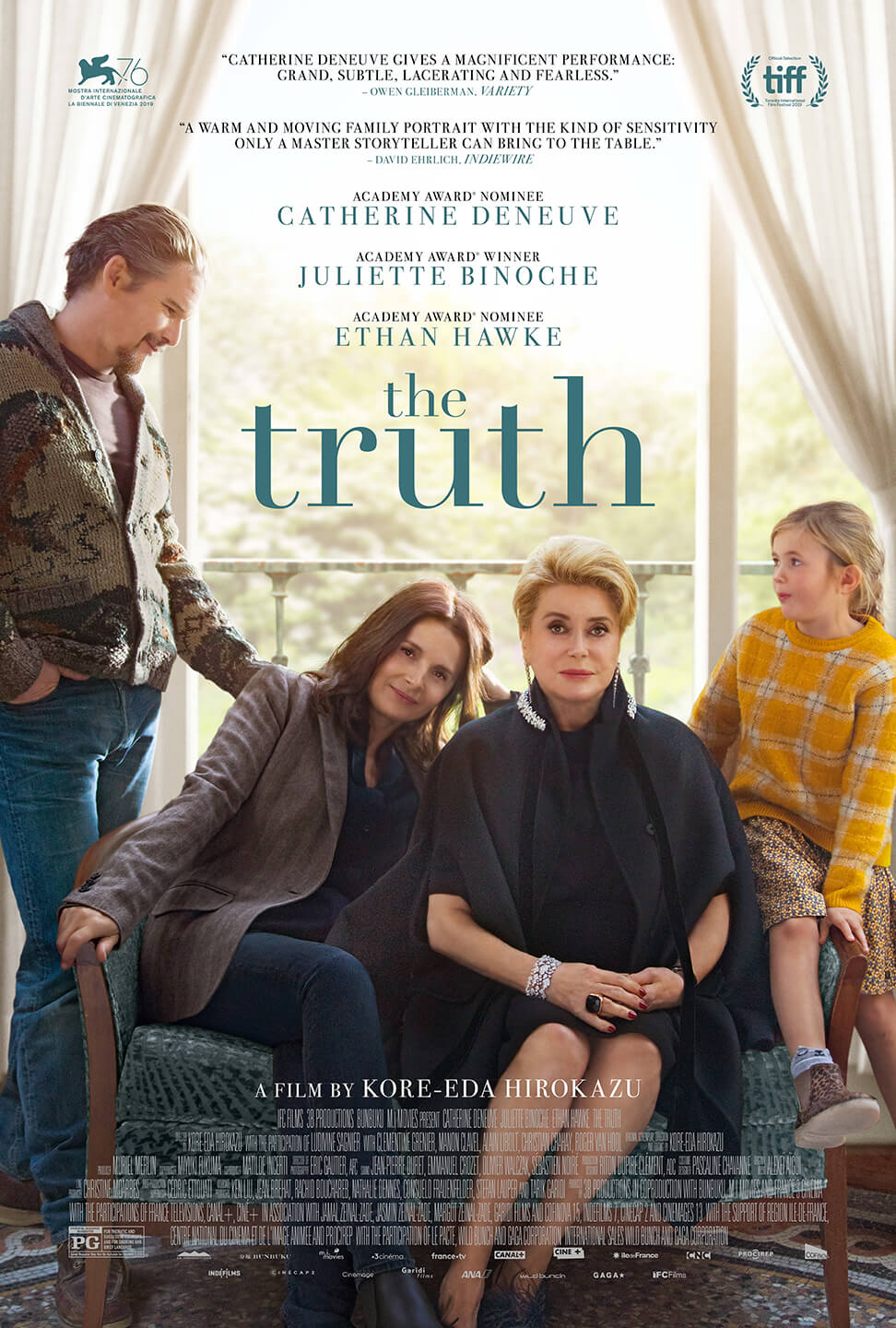

The most thematically unique aspect of Kore-eda’s The Truth must be its film industry backdrop, a purposeful and necessary structural device. Juliette Binoche plays Lumir, the screenwriter daughter of legendary French actress Fabienne, a thinly veiled Catherine Deneuve-esque character played by none other than Catherine Deneuve. (Fabienne is best known for The Belle of Paris; Deneuve starred in Belle du jour.) Lumir has a daughter with Hank (Ethan Hawke), a second-rate actor on a YouTube series, and they have come to Paris to visit Fabienne. The iconic performer, whose home is filled with vintage photos from Deneuve’s younger days, has just published her autobiography, called La vérité. But as a child who felt ignored and sidelined by her mother’s career, Lumir resents the text. She confronts Fabienne about the omissions and downright lies about their past, in particular a story where Fabienne claims to have been a present and loving mother. “I never tell the naked truth,” says Fabienne, who believes in fabricating a compelling story for her readers. It’s a condition of being an actress but not necessarily the quality of a nurturing parent, resulting in some hangups for Lumir.

At the same time, Fabienne struggles to connect with her latest part in a heavy-handed sci-fi drama called Memories of My Mother. During the production, Fabienne feels threatened by her up-and-coming costar Manon (Manon Clavel), who resembles Sarah Mondavan, a performer and family friend who helped raise Lumir and whose death may have been caused by Fabienne’s competitive nature. Fabienne omitted any mention of Sarah in her book, which Lumir sees as a betrayal. In the film-within-the-film, Fabienne plays an older version of a child whose mother, played by Manon, who people are calling the next Sarah Mondavan, periodically returns to Earth in brief visits from space, where Manon’s character must remain to stave off a deadly disease. Kore-eda investigates his titular motif through Memories of My Mother’s textual tiers, allowing his characters to use the material to reveal and process their past. Art has a way of getting to the truth far better than memories, and that notion carries through each character and delicate scene in The Truth.

On the periphery, yet also lovingly entwined, Kore-eda gives as much depth to the smaller supporting characters, most of which are men. But above all, there’s Charlotte, Lumir and Hank’s young daughter, wonderfully inhabited by Clémentine Grenier. The girl’s playful curiosity, the way she’s convinced that her grandmother has turned her absent grandfather into the large turtle that inhabits Fabienne’s back yard, is endearing. Hank, too, has a childlike appeal as a non-French speaker. He’s bewildered and a step removed from most conversations happening around him, so at one get-together, he sits at the children’s table and entertains the kids with silly tricks. It’s also worth noting how much nuance Kore-eda gives Fabienne’s live-in boyfriend, Jacques (Christian Crahay), who experiments with Italian cooking, or Luc (Alain Libolt), her longtime assistant who feels alienated by Fabienne’s persistent diva behavior. Each of these characters gives Kore-eda’s film texture, in the same way that Fabienne argues for the poetry of simple, stable cinematography in her films—which, incidentally, is how Éric Gautier shoots this film: relaxed passages that reveal characters through prolonged observation of their behavior.

On the periphery, yet also lovingly entwined, Kore-eda gives as much depth to the smaller supporting characters, most of which are men. But above all, there’s Charlotte, Lumir and Hank’s young daughter, wonderfully inhabited by Clémentine Grenier. The girl’s playful curiosity, the way she’s convinced that her grandmother has turned her absent grandfather into the large turtle that inhabits Fabienne’s back yard, is endearing. Hank, too, has a childlike appeal as a non-French speaker. He’s bewildered and a step removed from most conversations happening around him, so at one get-together, he sits at the children’s table and entertains the kids with silly tricks. It’s also worth noting how much nuance Kore-eda gives Fabienne’s live-in boyfriend, Jacques (Christian Crahay), who experiments with Italian cooking, or Luc (Alain Libolt), her longtime assistant who feels alienated by Fabienne’s persistent diva behavior. Each of these characters gives Kore-eda’s film texture, in the same way that Fabienne argues for the poetry of simple, stable cinematography in her films—which, incidentally, is how Éric Gautier shoots this film: relaxed passages that reveal characters through prolonged observation of their behavior.

The Truth cannot help feel like an earthy French drama by Arnaud Desplechin or Olivier Assayas, where layered characters reunite for a limited span of time, and while together, they work out some long-harbored conflicts. Something like Desplechin’s A Christmas Tale (2008) comes to mind, with notes of Assayas’ Summer Hours (2009) and Clouds of Sils Maria (2014)—particularly the latter film, where Binoche played an actress reconciling with her past and potential irrelevance given her age, which is echoed by her obsession with an upcoming and deliciously symbolic role. Films like these have a clever way of beguiling the viewer. They lure us with their cozy homes, decorated with fine art and comfortable furniture; the characters drink wine and eat luscious cuisine. Everyone’s dressed in elegant but relaxed clothing (Hawke, after Sinister and Juliet, Naked, plays another character in comfy-looking cardigans and worn t-shirts). However inviting these spaces and people seem, they also give way to raw, aching discussions about long-held resentments and uncomfortable secrets, some Fabienne would rather not confront; others she exposes through her acidic and self-absorbed behavior. At one point, she insults Hank’s acting as “imitation,” but isn’t much of her own life a carefully constructed artifice?

Compared to other rare detours in Kore-eda’s career—such as his sex toy love story Air Doll (2009) or his recent legal thriller The Third Murder (2017)—The Truth seems more aligned with his usual style and preoccupations than the surface implies. Consider that a plus. This is a drama in which Kore-eda uses the profession of acting as a metaphor for how family members often feel compelled to inhabit their assigned roles, and with that comes a certain degree of performance in our interactions with relatives. Deneuve and Binoche, two living legends, give terrifically natural and lived-in performances, and the pleasure of watching these two act opposite each other cannot be overstated. But their performances also serve the metatextual metaphor. Is the truth the personality we adopt when we’re around our family? Or does the truth only emerge when we consider the many ways in which we perform in various situations? Above all, Kore-eda settles on a beautiful and intricate lesson about human beings—how we only become fully formed individuals out of a messy assemblage of past experiences, divergent memories, and the lies we tell ourselves. Above all, Kore-eda reveals the irony of how art—often called lies or imitation of reality by aesthetic theorists—gets to the root of the truth better than reality does.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review