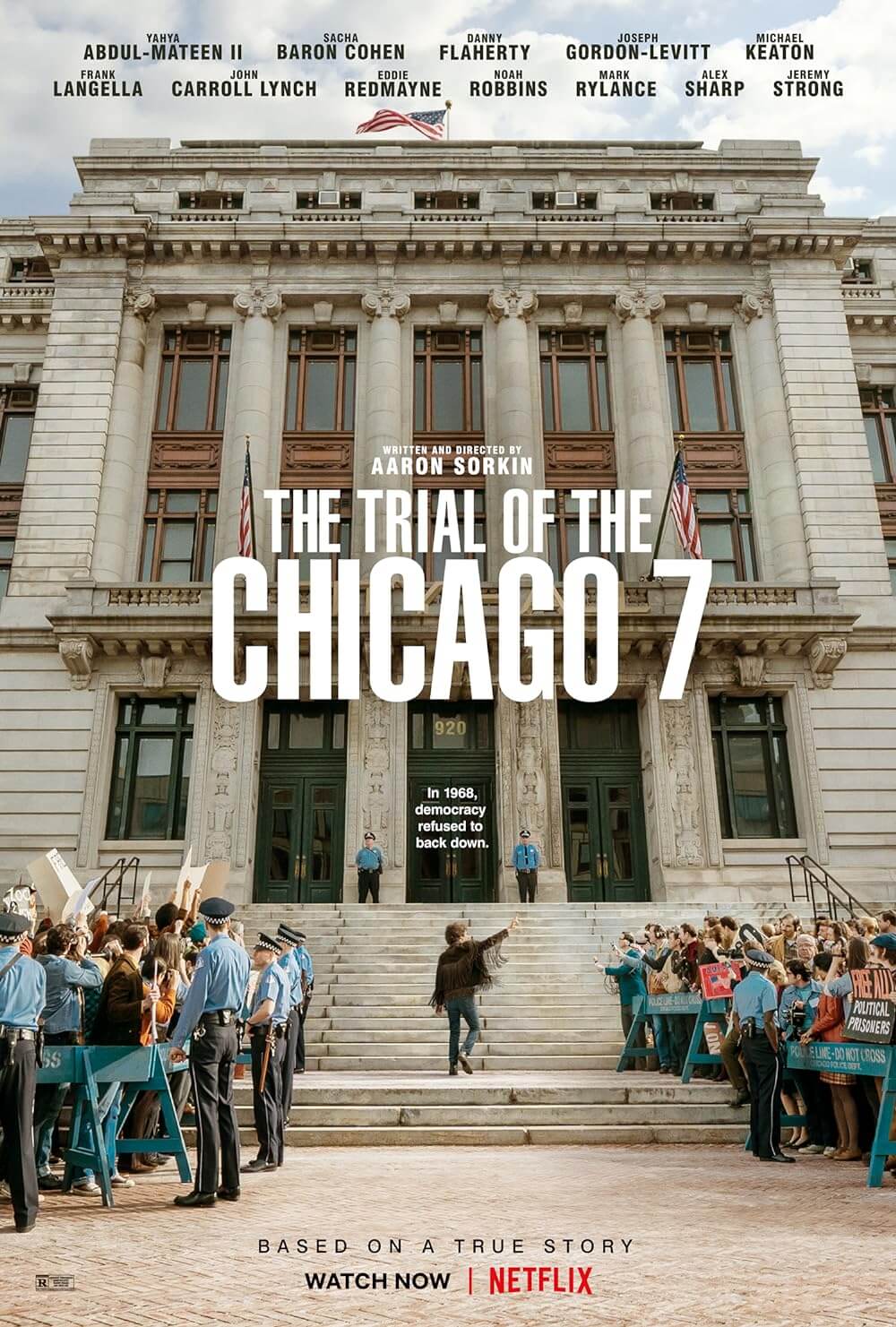

The Trial of the Chicago 7

By Brian Eggert |

Aaron Sorkin channels Frank Capra in The Trial of the Chicago 7, a Netflix release that manages to have crowd-pleasing airs, even though you’ll probably watch it in your living room. It harkens back to Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1938) or Meet John Doe (1941), where an idealistic minority stands up against an unbalanced bureaucratic force. In this case, it dramatizes the trial of seven defendants accused of conspiring to incite a riot at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Courtrooms have always been bombastic places in the movies, and Sorkin mines the real-life story for pieces of cinematic gold. His characters make grandiose speeches, his judge issues unjust orders from on high, and his emotions are earnest and sweeping. No wonder Steven Spielberg originally asked Sorkin to write a screenplay he planned to direct himself. But Sorkin shows he’s up to the task, drawing from the naturally dramatic situation and often using actual court testimony and events from the trial. To be sure, he doesn’t have to dig deep to find the inherently moving substance here, nor does he have to allude to its modern-day relevance. The historical parallels remain on the surface; no underlining is needed.

The events during and after the Chicago riots in Lincoln Park sprang from anti-Vietnam protests carried out by several political groups, some of them deemed “radicals” by the conservative majority of Nixon’s White House. When Nixon appointed John Mitchell (later one of the conspirators in Watergate) to Attorney General in 1969, they planned to make an example out of the opposition, turning the riot’s so-called organizers into scapegoats—despite the federal inquiry that determined the Chicago police were responsible for starting the riots. Mitchell selected eight figureheads from the liberal dissenters, who sought to end the draft and meaningless war in Vietnam, and arranged a drumhead trial, with charges that included conspiracy to cross state lines to incite violence. Although seven of the accused were actually involved in the protest, Mitchell also named national Black Panther Party chairman Bobby Seale, played by Yahya Abdul-Mateen II in the film, if only because the Nixon administration sought to target and discredit the Panthers. Although the trial was meant to serve as a public shaming of sorts, it exposed the case as decidedly unjudicial.

Sorkin already reinvigorated the courtroom drama in 1992 with A Few Good Men, injecting elements of corruption, loose legality, and blustering dialogue into the familiar territory. Here, the screenwriter, directing for the second time after Molly’s Game (2017), ratchets up the experience, using the actual events to inspire a fast-and-loose account. Take the breathless pre-credits sequence that establishes everything you need to know about the period in a few brief minutes. A montage of archival footage from Vietnam to the televised draft to political assassinations (RFK, MLK) sets the stage for the accused: The Students for a Democratic Society, a group that hopes to work within the system to change it, is run by Tom Hayden (Eddie Redmayne) and Rennie Davis (Alex Sharp). The pacifist family man David Dellinger (John Carroll Lynch) heads the Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam. The Yippie frontman Abbie Hoffman (Sacha Baron Cohen) approaches the trial with his partner Jerry Rubin (Jeremy Strong) like an absurdist stage performance, which, in many ways, it is. After all, the other two defendants, Lee Weiner (Noah Robbins) and John Froines (Danny Flaherty), seem to be included for no reason whatsoever.

Sorkin already reinvigorated the courtroom drama in 1992 with A Few Good Men, injecting elements of corruption, loose legality, and blustering dialogue into the familiar territory. Here, the screenwriter, directing for the second time after Molly’s Game (2017), ratchets up the experience, using the actual events to inspire a fast-and-loose account. Take the breathless pre-credits sequence that establishes everything you need to know about the period in a few brief minutes. A montage of archival footage from Vietnam to the televised draft to political assassinations (RFK, MLK) sets the stage for the accused: The Students for a Democratic Society, a group that hopes to work within the system to change it, is run by Tom Hayden (Eddie Redmayne) and Rennie Davis (Alex Sharp). The pacifist family man David Dellinger (John Carroll Lynch) heads the Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam. The Yippie frontman Abbie Hoffman (Sacha Baron Cohen) approaches the trial with his partner Jerry Rubin (Jeremy Strong) like an absurdist stage performance, which, in many ways, it is. After all, the other two defendants, Lee Weiner (Noah Robbins) and John Froines (Danny Flaherty), seem to be included for no reason whatsoever.

Sorkin’s ensemble only gets better with Mark Rylance stealing the film as William Kunstler, the rational defense attorney who stands for the seven, but not Seale, in a point of continuing frustration and eventual outrage. The prosecutor is Richard Schultz, played by Joseph Gordon-Levitt, a decent man who knows from the outset that Mitchell has given him an assignment with almost no legal foundation. Both attorneys suffer under the fussy senility of Judge Julius Hoffman (Frank Langella), a man who cannot get names correct and interrupts Schultz’s opening remarks to clarify that he and Abbie Hoffman are not related. The judge may be one of the most frustrating villains in recent cinematic memory, full of petty citations for contempt and clear biases throughout the trial. His cruelty steps into outright racism when, after Seale makes countless attempts to protest his presence in the courtroom without legal representation, he orders bailiffs to take Seale “into a room and deal with him as he should be dealt with.” Seale is beaten, bound, and gagged before being returned to court, where the judge manages to look surprised when he’s accused of racism.

While compressing timelines and taking poetic liberties with the material, Sorkin manipulates his audience’s sympathies like a master. As ever, his dialogue is mannerist and occasionally unnatural, adopting a stagelike rhythm that nonetheless drives the film’s momentum. His characters speak with crackerjack intelligence, wit, and timing that remains Sorkin’s distinct signature more than any visual flourish. His detractors rally against the way his characters speak, but this critic isn’t one of them. Although he and other playwright-turned-screenwriters (David Mamet, for instance) may not offer grand cinematics, their dialogue remains an authorial trademark. Still, The Trial of the Chicago 7 is a more palatable visual experience than Molly’s Game. Shot by Phedon Papamichael, a frequent collaborator with James Mangold and Alexander Payne, the film’s camerawork is fluid and coherent, and so is Alan Baumgarten’s editing. Much of the 130-minute runtime takes place in the courtroom; however, Sorkin frequently intercuts testimony with flashbacks to the events surrounding the protest, or Abbie Hoffman on stage, recounting his version of what happened in an anecdotal stand-up performance. These sequences can feel patchy at times, whereas the longer courtroom scenes keep the viewer rapt.

With Sorkin’s dialogue propelling the film, his actors become essential mouthpieces, and there’s not a rotten egg in the bunch. The showiest performance belongs, expectedly, to Cohen’s take on Abbie Hoffman—they’re both figures who are interested in comical stunts with a message, whether it’s Cohen revealing the character of Americans in Borat (2006) or Hoffman leading protests into the New York Stock Exchange. But as mentioned, Rylance, playing the famed civil rights attorney, proves most compelling in his clear-headed assessment of each miscarriage of justice in the proceedings (and there are many). The rest of the cast has at least one scene to shine, such as Lynch’s stirring outburst or Strong’s persistent romantic interest in the undercover agent who infiltrated his group. Michael Keaton even has a brief appearance, playing former Attorney General Ramsey Clark, using his onscreen persona to deliver a clear-cut character in two small yet significant scenes. But the entire ensemble has been carefully selected, making every scene feel like it contains another excellent performance.

With Sorkin’s dialogue propelling the film, his actors become essential mouthpieces, and there’s not a rotten egg in the bunch. The showiest performance belongs, expectedly, to Cohen’s take on Abbie Hoffman—they’re both figures who are interested in comical stunts with a message, whether it’s Cohen revealing the character of Americans in Borat (2006) or Hoffman leading protests into the New York Stock Exchange. But as mentioned, Rylance, playing the famed civil rights attorney, proves most compelling in his clear-headed assessment of each miscarriage of justice in the proceedings (and there are many). The rest of the cast has at least one scene to shine, such as Lynch’s stirring outburst or Strong’s persistent romantic interest in the undercover agent who infiltrated his group. Michael Keaton even has a brief appearance, playing former Attorney General Ramsey Clark, using his onscreen persona to deliver a clear-cut character in two small yet significant scenes. But the entire ensemble has been carefully selected, making every scene feel like it contains another excellent performance.

Sorkin wrote The Trial of the Chicago 7 for Spielberg back in 2007, and maybe that’s why a film about political corruption, systemic racism, police violence, and horrific judicial conduct veers toward the sentimental, almost lighthearted at times. (For a more severe take on the events, viewers should watch Brett Morgen’s animated documentary Chicago 10: Speak Your Peace from 2007.) Paramount Pictures developed the film, but they ultimately sold it to Netflix, given the beleaguered state of theatrical distribution in the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s difficult to imagine a historical courtroom drama earning oodles at the box-office now, or even in a normal situation, so perhaps the film’s debut on the streaming platform will mean a larger audience for this germane piece of entertainment. Much like Spielberg did with The Post in 2017, Sorkin has tapped into something. Whether it’s called Capraesque or Spielbergian, the label denotes a film that accesses our emotions and ideological sympathies in simple but undeniable ways. This is a film that feels vital for today in how the issues we face reflect those at stake in the late 1960s. And while its methods occasionally prove broad and engineered to be accessible, its optimism that some measure of ethical justice will prevail is an inspiring message that some of us desperately need.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review