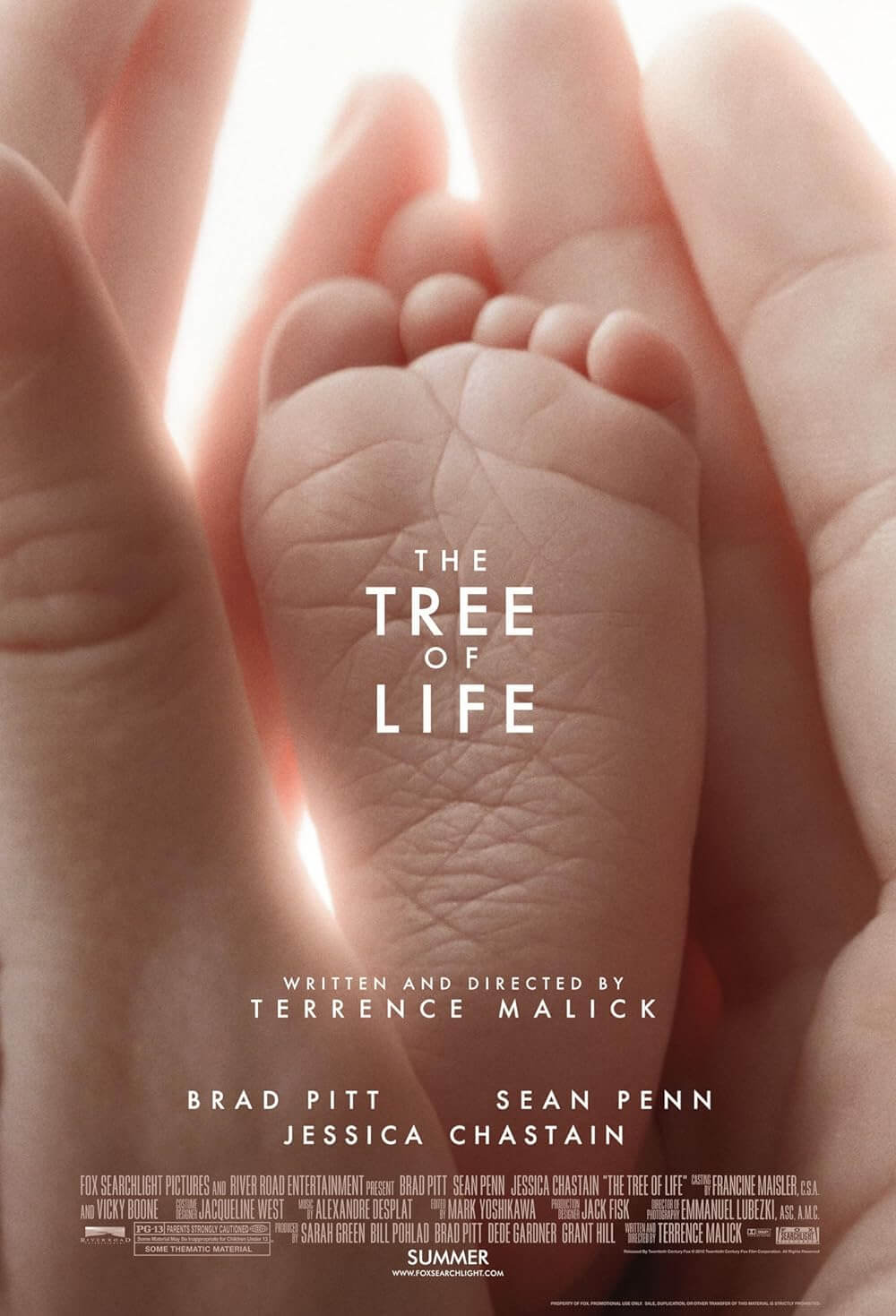

The Tree of Life

By Brian Eggert |

Primal and intuitive, Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life searches for connections between time, Nature, and memory for the director’s most graceful endeavor, an insightful work of art filled with gorgeous imagery and philosophical introspection. In this fifth feature in a career spanning forty years, the reclusive and enigmatic filmmaker weighs a young boy’s upbringing in 1950s Texas against the creation of Earth, asking questions bound to infect viewers with their beauty and spiritual reverberation. Akin to a visual poem, Malick’s assemblage of visuals took three years and five editors to piece together to realize this intense, stunning symphony, a picture the director had visualized in his head long before ever committing it to film. What he achieves is something singular, eruptive, and resonant, always provoking yet mysterious, while also undeniably affecting.

His lyricism bound by a quality of evanescence that may divide some viewers, Malick’s approach nonetheless delivers a major work of cinematic art best avoided by the bulk of commercial moviegoers. Contingent on an emotional interpretation that goes beyond a straightforward narrative, Malick proceeds with long patches of dialogue-less visuals and whispered voice-overs that require patience and curiosity from an audience. As with his last two increasingly elegiac works, The Thin Red Line and The New World, the film’s elusive manner will repel the masses. However, the effect is not unlike Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, a film to which The Tree of Life will be inextricably compared in its contagiousness. But more than Kubrick’s carefully measured investigation of the progress of humankind, Malick presents his questions within an impressionistic style whose structure must be experienced to grasp. And even then, the experience remains inexpressible.

Malick’s films have often been about people searching to understand humanity’s place in the world, both in relation to Nature and to their religious or existential beliefs. Beginning the film with a quote from the Book of Job, the filmmaker ponders, “Where were you when I laid the foundation of the Earth? Tell me, if you have understanding.” A formation of light, an image bookending the film, rotates onscreen, and gives way to the setting of Waco, Texas in the 1950s. Jack (Hunter McCracken), the eldest of three boys in the O’Brien family, is pulled apart by his parents, who personify two paths through life: The domineering father (Brad Pitt, in one of his best performances) represents pure nature, a demanding and unforgiving force; their mother (Jessica Chastain) represents the way of grace, a radiant figure brimming with unconditional love. As though time has no meaning in the film, Mr. and Mrs. O’Brien learn one of Jack’s brothers has died at the age of 19. They question why he was taken and what his death means. Leaping further ahead, a middle-aged Jack (played by Sean Penn), wanders his executive offices troubled, unable to find understanding between his past and present lives.

All at once, Malick shifts his attention to a cosmic birth in part designed by visual consultant Douglas Trumbull, creator of the special effects from 2001: A Space Odyssey. Images both astronomical and biological make us witnesses to the dawn of time. Gaseous masses form and peal apart; matter comes together to shape planets; volcanic explosions erupt in the darkness; primordial ooze bubbles; cells merge into whole organisms; jellyfish begin to fill oceans; a moment of compassion between dinosaurs. Then, once again, Malick settles back into the O’Brien’s homey Texas residence for an extended look at Jack’s adolescence and enduring conflict with his father, a square-jawed taskmaster whose dreams were “sidetracked” by his children, and therefore responds with fatherly antagonism. Through these transitions, Malick seems to restart the universe to place the O’Brien’s tragedy—which, intentionally, is barely detailed—into perspective, as if demonstrating how momentary and inconsequential death is when compared to the transcendence of love through time.

All at once, Malick shifts his attention to a cosmic birth in part designed by visual consultant Douglas Trumbull, creator of the special effects from 2001: A Space Odyssey. Images both astronomical and biological make us witnesses to the dawn of time. Gaseous masses form and peal apart; matter comes together to shape planets; volcanic explosions erupt in the darkness; primordial ooze bubbles; cells merge into whole organisms; jellyfish begin to fill oceans; a moment of compassion between dinosaurs. Then, once again, Malick settles back into the O’Brien’s homey Texas residence for an extended look at Jack’s adolescence and enduring conflict with his father, a square-jawed taskmaster whose dreams were “sidetracked” by his children, and therefore responds with fatherly antagonism. Through these transitions, Malick seems to restart the universe to place the O’Brien’s tragedy—which, intentionally, is barely detailed—into perspective, as if demonstrating how momentary and inconsequential death is when compared to the transcendence of love through time.

From a purely technical standpoint, Malick’s production looks spectacular. Lovely scenes in Nature depict flora and fauna at their most sublime, while Jack Fisk, Malick’s production designer since The Thin Red Line, breathes life into the idealized vision of the 1950s American home. But Malick doesn’t shy away from the uglier yet natural aspects of humanity, as within Jack’s frustration and lasting angst come moments of violence and “experimentation” that may be shocking, the American ideal tainted. Fisk, along with Trumbull, also attains awe-inspiring sights during the film’s celestial interlude, the plays of light bursting through darkness or emerging from behind a massive spatial body unparalleled in their beauty. Music surges through these narrative and visual strains, offering countless classical pieces from Bach to Mahler, combined with original music from Alexandre Desplat. In the same way that music provides a foothold and tonal bond throughout 2001: A Space Odyssey, it provides Malick with a magisterial sense of wonder and searching.

Indeed, Emmanuel Lubezki’s always-moving camera searches for answers just as the characters and audience do. Employing unusual perspectives, some enhanced by wide-angle lenses and others by unique camera positioning (a wonderful upside-down image makes shadows look like blithe spirits of children playing), Lubezki’s restless approach echoes Malick’s ongoing cinematic investigation. Visuals familiar to Malick enthusiasts, such as recurring images of flowing water and rays of light peering through trees, have incredible metaphorical significance here, as though our clear understanding of our ethereal place in the universe (represented by light) has been impeded by something material (represented by leaves, or any of the many filters through which light passes). Looking past our physical world, first the smaller problems of humanity, second our physical existence within all of creation, will bring the kind of understanding achieved in the final scenes of the film, a congregation of souls on a beach.

Then again, what it all means becomes a question of subjectivity. No matter your religious views, there’s something profoundly exploratory about The Tree of Life that will reach deep inside and tempt you to consider the greater meaning of how humanity fits into the cosmos. Impossible to ignore, Malick’s use of religious iconography is penetrated and expanded by his reaching into the beyond, suggesting that whatever the universe holds for humanity, it’s greater than anything tangible or definable, even the concept of “God”. Afterward, I was struck with perceptions of reincarnation and transmigration, not unlike the feeling one takes away from The Thin Red Line, except more poignant, in that Malick seems to evoke the human capacity for love through the movement of the soul to somewhere outside earthly or spatial truth. Surely this place could be interpreted as Heaven, but that answer would be too easy, and far too literal for the poet-filmmaker.

Then again, what it all means becomes a question of subjectivity. No matter your religious views, there’s something profoundly exploratory about The Tree of Life that will reach deep inside and tempt you to consider the greater meaning of how humanity fits into the cosmos. Impossible to ignore, Malick’s use of religious iconography is penetrated and expanded by his reaching into the beyond, suggesting that whatever the universe holds for humanity, it’s greater than anything tangible or definable, even the concept of “God”. Afterward, I was struck with perceptions of reincarnation and transmigration, not unlike the feeling one takes away from The Thin Red Line, except more poignant, in that Malick seems to evoke the human capacity for love through the movement of the soul to somewhere outside earthly or spatial truth. Surely this place could be interpreted as Heaven, but that answer would be too easy, and far too literal for the poet-filmmaker.

The Tree of Life demands an audience that does not require cinema to progress logically. Trying to connect one image to the next on an intellectual level will leave viewers scratching their heads, and possibly frustrated, while others may embrace what borders on narrative resistance (hence the simultaneous boos and applause reported from its debut at Cannes, where it won the Palme d’Or). Watch instead as though Malick has direct access to your emotional understanding of the world, and perhaps you’ll walk away feeling like you’ve just witnessed something profound. You may not be able to pinpoint with words how it all comes together, but the beauty and power of Malick’s imagery and impressionistic approach to filmmaking convey another ponderous picture, the director’s most ambitious and lyrical work yet. Although a landmark piece of cinema history, its beguiling sincerity and sheer beauty are bound to leave committed viewers moved in ways they may never understand but cannot deny.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review