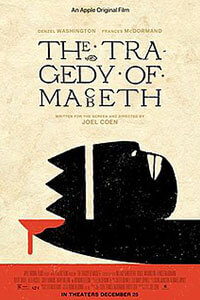

The Tragedy of Macbeth

By Brian Eggert |

Many directors have translated Shakespeare to film, and the results vary depending on the balance between form and drama. If the filmmaking calls too much attention to itself, the Bard’s dialogue and story suffer. When Kenneth Branagh turned Hamlet into a four-hour masterpiece in 1996, he spared no expense, but his cast’s towering performances matched the elaborate production design. By contrast, a minimalist approach has also worked well. Orson Welles adapted several Shakespeare plays to the screen, usually employing spare sets to focus on the actors, editing, and camerawork. As dramaturgy goes, Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth distinguishes itself with its elaborately conceived and condensed version of Shakespeare’s shortest, bloodthirstiest play. Made without his brother, Ethan, the film eschews most of the idiosyncrasies and ironies associated with the Coens’ work in favor of a stark, black-and-white vision in the squared Academy aspect ratio, evoking the prisonlike fate of its protagonist.

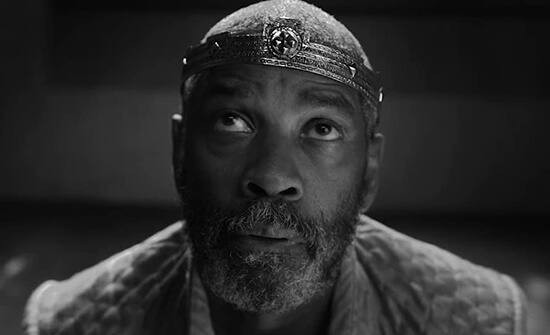

In a stroke of brilliant casting, Coen enlists Denzel Washington as the ambitious thane, who learns of his inevitable crown and then proceeds to cut through friends and competition to attain it. Frances McDormand, Coen’s wife and creative partner here, reprises her role from the stage as Lady Macbeth. The two, both perfectly cast, play their parts like a supportive couple committed to their mutual ascent, whereas other adaptations have emphasized Lady Macbeth’s manipulation of her husband. As for Washington, a theater regular, it’s easy to forget how versatile he can be given his presence in so much commercial fare. He portrays guilt and inner conflict with sublimely twitchy paranoia, and few actors can perform a gradual coming-apart-at-the-seams so well (see ‘Mo Better Blues or Training Day). McDormand is clearly at her best and loving it, lending Lady Macbeth the careful logic of a level-headed partner in crime. Washington and McDormand carry the weight of their characters’ choices, experiences, and hallucinations (or “daggers of the mind”) on their weathered faces, desperate in their middle-age to exploit this last chance at glory. All the while, Carter Burwell’s score is almost nonexistent, save for the nagging thumps that haunt the castle and pound on the couple’s fraying minds.

It might seem impossible to upstage performers of such caliber, but Kathryn Hunter does just that. With only a few film credits and a long career on the stage, Hunter is unforgettable as the witches, traditionally represented as three figures, but here standing like Death in The Seventh Seal (1957). Coen uses watery reflections and shadowy duplicates to suggest that Hunter’s witch is a singular presence, and what’s more, capable of contorting her body in abject ways (all Hunter, not an effect). Her voice, resounding across every speaker in the sound mix, recalls Mercedes McCambridge’s work as the demon’s voice in The Exorcist (1973). It’s a low, haunting aural reverberation that causes goosebumps and invades Macbeth’s mind, thus the viewer’s. Elsewhere, she convincingly appears as the older man who protects Fleance, Banquo’s son, after Macbeth orders them both assassinated. Hunter’s performance might be the standout in a film that also stars Brendan Gleeson as Duncan, Corey Hawkins as Macduff, and a particularly haggard Stephen Root as Porter.

Coen’s adaptation slices through the Scottish play, tossing meaty characters and subplots aside, and reduces the story to its bones, sometimes leaving confusing character introductions and spatial transitions. For example, when Siward (Richard Short) confronts Macbeth for an impressively choreographed duel sequence (featuring a monumental shove), I wondered if Siward had even appeared onscreen yet. Coen’s adaptation, running just 105 minutes, proves as austere as Stefan Dechant’s production design. At first glance, The Tragedy of Macbeth looks like Welles’ monochrome versions of Macbeth (1948) or Othello (1952) in their stagelike severity and use of high-contrast lighting. But Coen’s plan has more in common with Charles Laughton’s work on The Night of the Hunter (1955), where whole patches of the screen appear engulfed in the blackness or whiteness of negative space or stony textures of the castle’s blank walls.

At one point, a circular spotlight illuminates a character, and Coen’s visual connections between the stage and cinema become unmistakable. Cinematographer Bruno Delbonnel’s compositions haven’t been matched in the Coens’ career for twenty years, not since the black-and-white noir style of The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001). Most of the sets appear unadorned here; there are no paintings or tapestries in the Scottish castle, yet it’s composed of severe angles that nod to German Expressionism. The structure looks geometric, almost futuristic in design. Although Coen captured much of the film on soundstages, there’s plenty of green screen work here, too, creating visual anachronisms between the old and new—emphasized by the rounded corners of the boxy aspect ratio. Coen uses CGI fog to transition from one scene to the next, CGI ravens to show the witch’s transformation, and CGI landscapes to fill the backdrop, ultimately distracting from the drama.

Conceptually, Coen’s production makes bold choices that one cannot fault except for their execution on a frequently digitized stage that detracts from the story and acting. For example, when the final frame throws a conspiracy of ravens at the viewer, it looks like CGI ink flowing outward, ending the film on a silly looking note. Other examples, such as the imposing image of Lady Macbeth on a cliffside or her haunting sleepwalk through the castle, have a beautiful simplicity. Still, the look feels at times like Welles by way of Zack Snyder’s 300 (2007). Granted, the film isn’t going for muddy realism as, say, Roman Polanski’s 1971 version did. Instead, Coen emphasizes the staginess at every opportunity, such as portraying Birnam Wood coming to Dunsinane in a veritable hallway of trees. With digitization being the modern stage, Coen’s film embraces the format. But this critic felt consumed by many of the visual choices and distanced by the storytelling, which is a shame, given the film’s monumental performances.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review