Reader's Choice

The Toxic Avenger

By Brian Eggert |

French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu published Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste in 1979, one of the first major studies on taste as a social construction. He argued that good taste was “asserted purely negatively, by the refusal of other tastes.” After one scrapes away the abject horror and disgust experienced in a visceral or ideologically negative reaction, the remainder must be the product of good taste. But only the offended tastebuds of a distinct, mostly bourgeois group implant the good taste canon, according to Bourdieu, and thus, these so-called elites draw the acceptable boundaries of mainstream culture. Cult films rally against good taste, defying the sociopolitical, economic, and cultural elitism of tastemakers. Such bad taste fare transgresses the conventional consciousness and dominant ideology. And there once was a time, established in the 1920s with the emergence of Classical Hollywood and lasting through the early 1960s, when a prevailing cultural outlook permeated the cinema. From the 1960s until the dawn of the Digital Age, cult films could still be transgressive in the face of a perceived uniformity in American culture. But as the overall culture continues to fragment and cults progress into subcultures, which in turn become entirely independent of one another, cult film has transformed into a commercially proven and exploitable market for cult-style entertainment today. As a result of this transformation, The Toxic Avenger, released in 1984 by Troma Entertainment, seems almost cute today.

Bringing up French sociology and the fragmentation of cultural values in relation to The Toxic Avenger is not meant to suggest any feeling of loss or regret over the near eradication of the elitism of good taste in contemporary times. In an effort to preserve itself, the social hierarchy of good taste throughout history has suppressed countless artists from expressing themselves openly, forcing them into cult modes of exhibition. Rather, my initial remarks are meant to deplore the normalization and commercialization of transgressiveness in cinema. Antiauthoritarian cultists have become so commonplace that they have transformed into subcultures able to inhabit entirely different spaces without overlap, whether they exist online or in the real world. Their autonomy dissolves the oppositional relationship of good and bad taste, which has both positive and negative effects. On the positive end, it grants the creators of transgressive art a wider audience that supports it both financially, in terms of establishing a reliable marketplace for their works, and existentially, in that their audience has been demarcated by midnight madness screenings, web forums, and countless other subcultural sites. On the negative end, the institutionalization of cult films in pop-culture has robbed them of their potency, rebellion, and essential alternativeness—cult films have become just another option on the search bar.

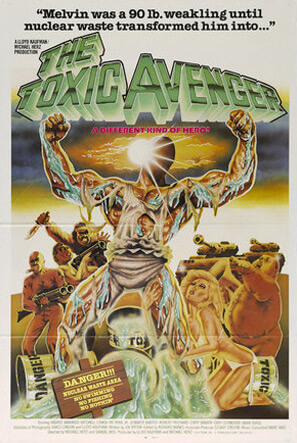

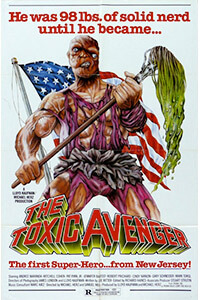

In a way, my belief in the death of truly transgressive cult cinema began with The Toxic Avenger, as evidenced in the movie’s modest franchise success. This “Troma Team Release” was shot in New Jersey for a meager $500 thousand by Lloyd Kaufman and Michael Herz, the founders of Troma, and over the subsequent decades, its brand has earned them millions. After its meager premiere in 1984, the movie cultivated a small but loyal audience before its expanded release in 1986. Its profits led to three diminishing sequels—The Toxic Avenger Part II (1989), The Toxic Avenger Part III: The Last Temptation of Toxie (1989), and Citizen Toxie: The Toxic Avenger IV (2000). There was a children’s Saturday morning cartoon, Toxic Crusaders, made in 1991 in the wake of the popular Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles animated series—after which mutants born of toxic waste became mainstream. Troma then spread their intellectual property across comic books, action figures, books, video games, and a popular 2008 musical. All of this derived from a sordid little freakshow-of-a-movie that bears curious similarities to a Marvel Comic.

In a way, my belief in the death of truly transgressive cult cinema began with The Toxic Avenger, as evidenced in the movie’s modest franchise success. This “Troma Team Release” was shot in New Jersey for a meager $500 thousand by Lloyd Kaufman and Michael Herz, the founders of Troma, and over the subsequent decades, its brand has earned them millions. After its meager premiere in 1984, the movie cultivated a small but loyal audience before its expanded release in 1986. Its profits led to three diminishing sequels—The Toxic Avenger Part II (1989), The Toxic Avenger Part III: The Last Temptation of Toxie (1989), and Citizen Toxie: The Toxic Avenger IV (2000). There was a children’s Saturday morning cartoon, Toxic Crusaders, made in 1991 in the wake of the popular Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles animated series—after which mutants born of toxic waste became mainstream. Troma then spread their intellectual property across comic books, action figures, books, video games, and a popular 2008 musical. All of this derived from a sordid little freakshow-of-a-movie that bears curious similarities to a Marvel Comic.

Banking on a counterculture attuned to sex, blood, and filth, Kaufman and Herz started their production and distribution company in 1974. Troma produced—and still makes—low-budget titles that could only aspire to the schlocky quality of Roger Corman’s cheapo New World Pictures movies. Back in the 1970s and 1980s, Troma titles first screened on New York’s 42nd Street, better known as The Deuce, where grindhouse theaters ran the era’s most salacious material for an underground market of weirdoes, renegades, perverts, mavericks, and outsiders. There, Kaufman’s name was already well established for a string of X-rated movies. Under the Troma label, Kaufman and Herz branched out into controversial splatterfests and raunchy sex comedies, with titles like Bloodsucking Freaks (1976), Squeeze Play (1979), and Surf Nazis Must Die (1987). Nothing was sacred; taboo subjects provided the basic ingredients of Troma’s nasty spoofs. And along with similar production companies of their ilk, Troma’s cheesy, trashy releases offended so-called good taste and engendered an audience devoted to their cultish output.

Watching The Toxic Avenger is not an experience rooted in empathy. Today it would be called a meta-experience in which the text is less important than the extratextual commentary on display—a layer of satire that involves the viewer outside of narrative, where the filmmakers wink at their audience through every absurdist plot machination or debased character detail. The story, however thin, follows Melvin Ferd (Mark Torgl), an annoying, unsympathetic nerd who mops up the sweat of elitist assholes at the health club in Tromaville, the “toxic waste dumping capital of the world.” Melvin is perpetually bullied by a group of fitness-obsessed beautiful people, led by the “stressed” Bozo (Gary Schneider), whose gang of hyper-zonked hit-and-run killers play their own version of Death Race 2000 in a sadomasochistic game. After a cruel prank that involves a tutu and a sheep, Melvin falls into an open vat of radioactive sludge, causing him to melt and combust into flames in a bubbly metamorphosis. He emerges as “the monster hero,” a local celebrity who rescues victims from Tromaville’s criminal gangs using a cartoon-inspired brand of violence (note his punching bag routine on the faces and groins of his enemies).

Kaufman and Herz’s treatment of the villains is telling, as they’re portrayed as racist, child murdering, drunk driving, and churchgoing degenerates that beat up elderly women and run over helmeted adolescents with their vehicles. Their police force is run by a German-accented officer prone to latent Nazi gestures, while Tromaville’s officials either have terrible combovers or appear morbidly obese. This mockery of cultural elites and authority figures reeks of Troma’s particular antiauthority streak, but not even the good guys escape unscathed. Melvin, later dubbed “Toxie,” has transformed into a melty-eyed rage monster who lives in the city dump, although, hilariously, he has the buttery voice of Kenneth Kessler. Toxie soon rescues the blind, optimistic Sara (Andree Maranda) from another of Tromaville’s gangs (after they kill her seeing eye dog in a moment that friends to animals will want to unsee), and they quickly begin a love affair. Meanwhile, her sightlessness is the subject of cheap pratfalls and gags. Together, they have silly, endearing romance—and not without an eww factor during their lovemaking.

Kaufman and Herz’s treatment of the villains is telling, as they’re portrayed as racist, child murdering, drunk driving, and churchgoing degenerates that beat up elderly women and run over helmeted adolescents with their vehicles. Their police force is run by a German-accented officer prone to latent Nazi gestures, while Tromaville’s officials either have terrible combovers or appear morbidly obese. This mockery of cultural elites and authority figures reeks of Troma’s particular antiauthority streak, but not even the good guys escape unscathed. Melvin, later dubbed “Toxie,” has transformed into a melty-eyed rage monster who lives in the city dump, although, hilariously, he has the buttery voice of Kenneth Kessler. Toxie soon rescues the blind, optimistic Sara (Andree Maranda) from another of Tromaville’s gangs (after they kill her seeing eye dog in a moment that friends to animals will want to unsee), and they quickly begin a love affair. Meanwhile, her sightlessness is the subject of cheap pratfalls and gags. Together, they have silly, endearing romance—and not without an eww factor during their lovemaking.

That the relationship between Toxie and Sara resembles the one between Marvel Comics’ Fantastic Four superhero Ben Grimm, aka The Thing, and his blind love interest Alicia Masters, is no coincidence. Kaufman and Herz draw from a wealth of Marvel influences, chief among them the phenomenon of average citizens being endowed with super-strength from an otherwise deadly source. The Thing, along with his three compatriots, was imbued with superpowers from the radiation in a cosmic ray storm; Spider-Man gained his abilities from a radioactive spider; the X-Men were granted abilities through mutations; Daredevil was blinded by a radioactive substance. Most of all, The Toxic Avenger borrows aspects of its form from The Incredible Hulk television series (1977-1982), about Dr. Bruce Banner’s shifts into a green bodybuilder after he’s exposed to gamma radiation. Both the Hulk and Toxie are played by muscle-bound actors (Lou Ferrigno, Mitch Cohen) augmented by a few cheap prosthetics, both roar their way through street-level battles, and their public both fears and celebrates them. With its foundation so closely mirroring that of a Marvel superhero, no wonder The Toxic Avenger catapulted Troma from an underground production company into a commercially viable distributor.

Of course, no one would mistake The Toxic Avenger for today’s blockbusters of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Kaufman and Herz may adopt a Marvel Comic setup, but this foundation is used to unleash a series of base jokes, C-grade effects, and over-the-top violence in the face good taste. Toxie tears arms out of a bad guy’s sockets, pokes eyes out of a gangmember’s head, rips the intestines from the fat mayor’s stomach, delivers beatings to a man’s groin, smushes a woman in a dry cleaning press and then stuffs her in a dryer, sears a goon’s hands in a deep frier, and conducts no end of atrocious acts that, in any other scenario, would be seen as horrific. However, given the intentionally comic-booky tone of the movie, every normal reaction contains another layer that appropriately mutates it into an unlikely, pleasantly rebellious one. Kaufman and Herz don’t stop at violence, either. Sexuality becomes a twisted affair in the movie, with a woman in Bozo’s crew masturbating to pictures of a dead child’s corpse, the presence of 12-year-old white slaves, and the gross-out factor of Toxie and Sara in bed. Even the aural experience of The Toxic Avenger betrays the acceptable as, typical of Troma releases, every line of dialogue is shouted at an abrasive decibel. Responses of horror and aversion are replaced by humor and glee—it’s a celebration of its own affronts to cultural sensitivities and the outsider status of such baseness. Nevertheless, the movie isn’t about inclusivity for those not accepted as normal, given its moments of homophobia and racism against Asian cultures.

But watching The Toxic Avenger isn’t about literalism or taking the material seriously as a text; it’s about identifying with Troma’s defiance of good taste and low culture, therein celebrating its excessive forms of deviancy in all their many violations. The typical aesthetic definitions of good art, such as beauty and meaning, become the target, and the subversion itself becomes the movie’s cult value. The system of taste—a social construction shaped by the preeminent moral and class systems of culture—is thus redefined and liberated through an experience like The Toxic Avenger. However, given the omnipresence of counter-cultural movies, or faux cult films that have sought to exploit or commercialize cult audiences (see Repo! The Genetic Opera), cultism has resulted in baseline subcultures that no longer disobey, infringe, or offend as part of an oppositional relationship. They have simply erected subcultural boundaries, inside of which deviance and bad taste become the norm and, furthermore, have no antithetical cultural exchange value. And so, while The Toxic Avenger once stood as a cinematic act of grotesque hilarity and rebellion, somewhere between its many sequels and its musical adaptation, the movie has become almost commonplace in the normalization of the cult film phenomenon. Regardless, it’s no less entertaining for its neutered lack of transgressiveness.

(Editor’s Note: This review was commissioned on Patreon. Thank you for your support, Dustin!)

Bibliography:

Bordieu, Pierre. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Rutledge, 1984.

Landis, Bill. “Tromatized.” Film Comment, vol. 22, no. 4, 1986, pp. 77–80.

Gorfinkel, Elena. “Cult Film or Cinephilia by Any Other Name.” Cinéaste, vol. 34, no. 1, 2008, pp. 33–38.

Mathijs, Ernest and Xavier Mendik, editors. “Cult consumption.” The Cult Film Reader. New York: Open University Press, 2008, pp. 369-379.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review