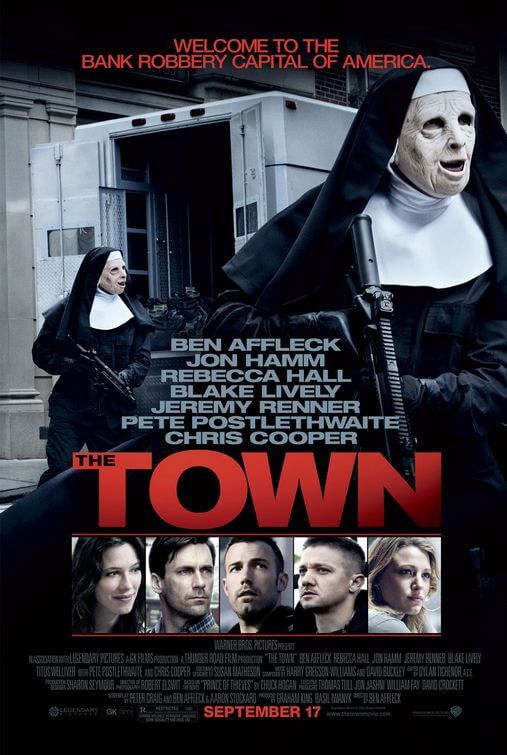

The Town

By Brian Eggert |

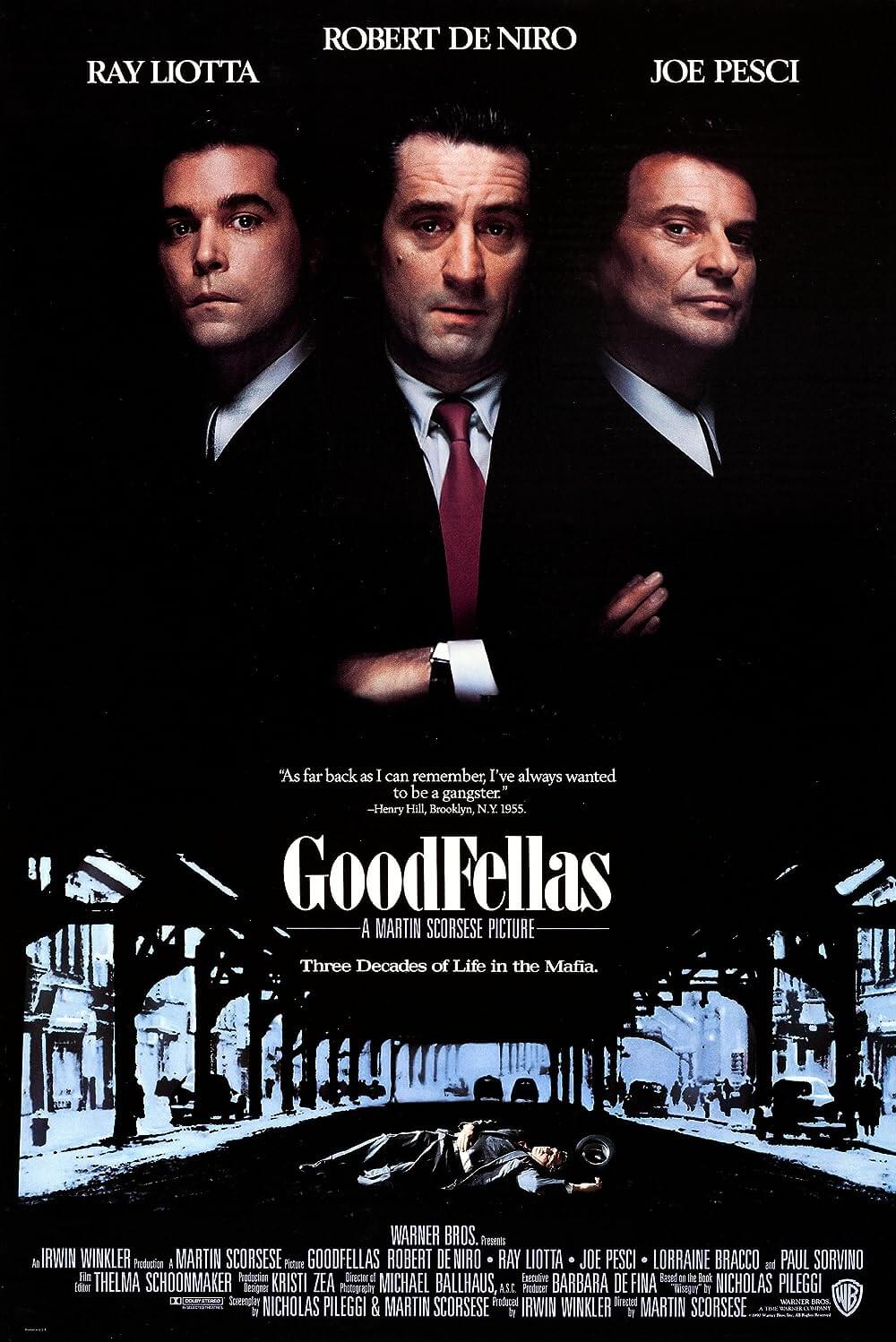

Ben Affleck follows up his 2007 directorial debut Gone Baby Gone with another foray into his home soil, The Town, an exciting and modestly moving Boston crime picture based on Chuck Hogan’s novel Prince of Thieves. Affleck directs himself and an impressive cast in yet another Hollywood film clearly inspired, both in style and content, by Michael Mann’s Heat, complete with loud machine guns echoing in city streets after elaborate heists-gone-wrong. Though, Affleck’s cramped Boston neighborhoods lend intense claustrophobia to scenes of suspense that Mann’s depiction of Los Angeles lacks, a characteristic that has greater meaning in the narrative here, and carries the weight of the script by Affleck and co-writers Aaron Stockard and Peter Craig.

Set in the rough neighborhood of Charlestown, the film informs us that this one square mile stretch has produced more armored car thieves and bank robbers than anyplace else in the country. In the opening robbery sequence, a four-man crew donning theatrical skull masks holds up a bank and takes the manager, Claire (Rebecca Hall), hostage. They let her go, but the brains of their operation, Doug MacRay (Affleck), opts to keep tabs on her, to make sure she didn’t see anything that will give them away. MacRay volunteers if only so his right-hand man, the hot-headed Jem (Jeremy Renner), doesn’t unnecessarily kill the possible witness. But as he follows up with the traumatized Claire from afar, MacRay can’t help but be drawn in; the two begin a dangerous and intimate romance where Claire remains none-the-wiser about her new boyfriend’s identity.

Having put himself through AA and cleaned up his life (aside from the robberies), MacRay reassesses the risks he’s taking in view of Claire. He decides to complete the all-too-common goal among thieves, the omnipresent “one last job”, and escape to Florida with her. But leaving Charlestown doesn’t come easy; the block’s unspoken code of honor demands that MacRay respect certain obligations. MacRay owes Jem, who served a nine-year stint in prison to protect his brotherly friend. There’s also Jem’s drug-rattled sister, Krista (Blake Lively), whose baby MacRay insists isn’t his, despite his willingness to occasionally bed the child’s mother. Worst of all is Fergie (Pete Postlethwaite), the local crime boss that never allows people to just walk away, as he threatens MacRay in a magnificently dangerous scene while butchering roses in his flower shop.

The kinetic energy throughout, propelled by the precision of Robert Elswit’s cinematography, keeps the momentum going before you realize some of the main characters are very one-dimensional. Take Agent Frawley (Jon Hamm), the determined cop investigating MacRay’s crew; he never earns a description beyond his occupation, unlike the Al Pacino character in Heat whose determination was defined by his broken family. Hamm does what he can with the role, but the problem resides in the script. Rather than develop the Frawley character and complicate the questionable morality at the film’s center, Affleck simplifies the audience’s job by suspending the viewer in MacRay’s world, which makes ventures into police territory feel unfamiliar. Affleck takes great care to represent the neighborhood atmosphere of his setting, just as he did in Gone Baby Gone, and he uses it here to potent effect during car chases down Boston’s narrow roads or during the robbery of Fenway Park.

Confessional-esque exchanges between Claire and MacRay take their relationship to affecting levels, even if the script doesn’t explain why a nice non-Charlestown girl falls for a rough-and-tumble hood covered in tattoos. It doesn’t really need to, since Hall and Affleck appear comfortable in each other’s presence, their performances genuine and likable. This is among Affleck’s best and most impressive roles (which are otherwise few and far between). Likewise, Renner proves last year’s Oscar nomination for The Hurt Locker wasn’t a fluke; he emits incredible menace by remaining coolly threatening in the scene where he catches Claire and MacRay together. Chris Cooper also appears in a single-scene cameo as MacRay’s prison-dwelling father, acting as a warning sign of things to come should MacRay get caught.

The story may be familiar territory for crime movie aficionados, but Affleck’s capable direction and all-around remarkable performances should impress viewers still unconvinced by Affleck’s talent behind the camera (still, Gone Baby Gone remains the stronger film on Affleck’s directorial resume). Though comparisons have been made to Heat, Affleck’s The Town best aligns with the influx of highly dramatic Boston-centric films released in recent years, namely Eastwood’s Mystic River and Scorsese’s The Departed. The film has the city written all over it, evident in the on-location street photography, aggressive temperament of characters, and predominance of dropped Rs among the cast’s collective brogue. If Affleck hasn’t already discovered that this is his niche, he’s encouraged to continue bringing us well-executed Boston crime stories like this one.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review