The Thing

By Brian Eggert |

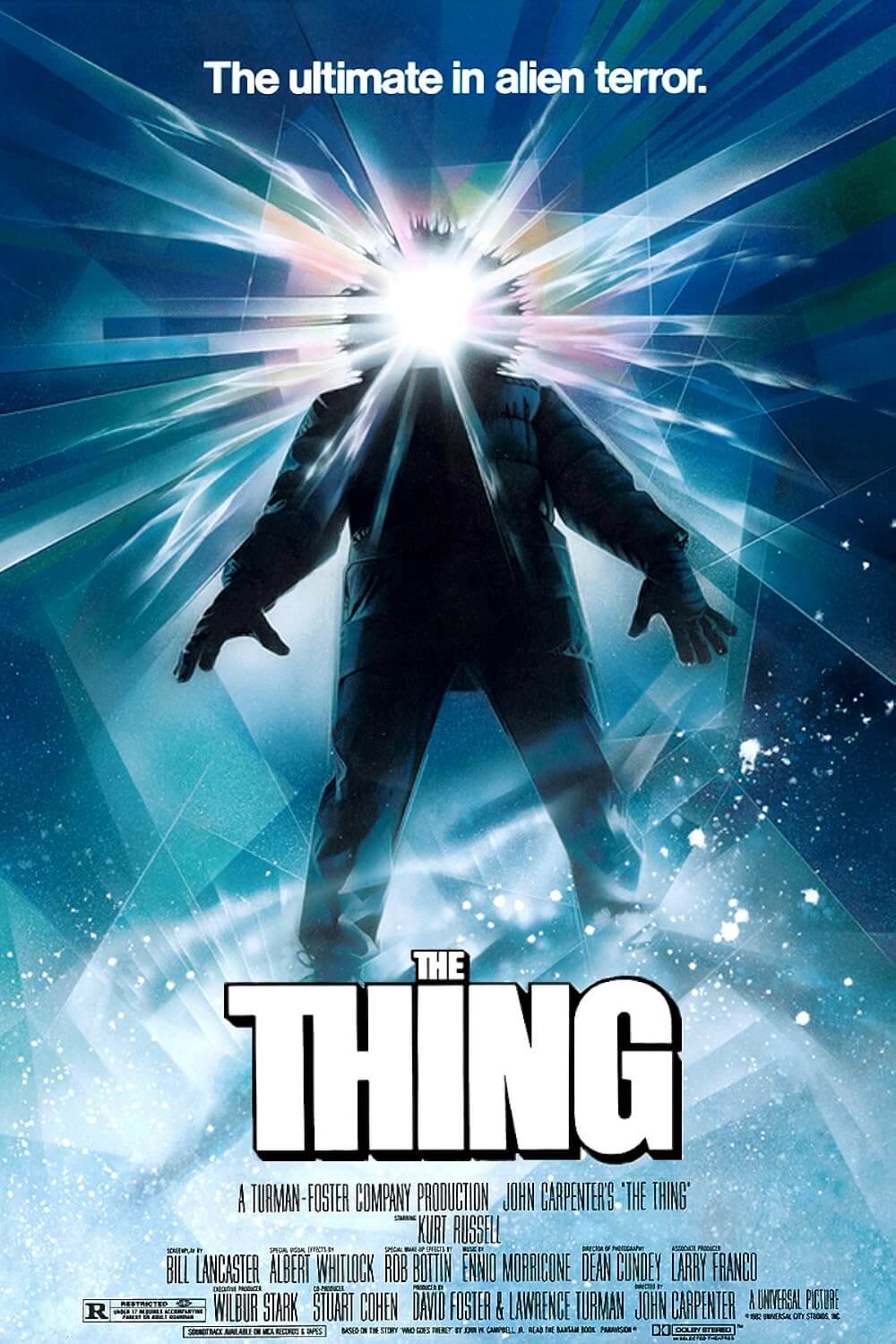

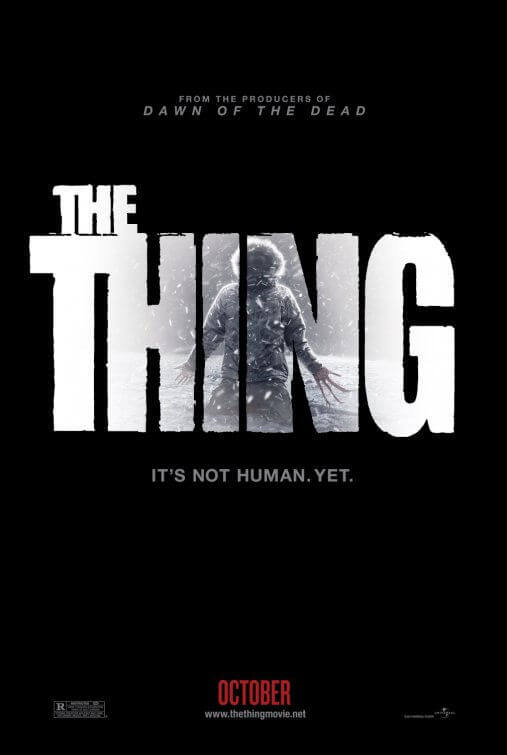

In what amounts to elaborately conceived fan fiction, Universal’s pseudo-prequel to John Carpenter’s 1982 classic The Thing, which itself was a remake of Howard Hawks’ version from 1951, contains little of the craft or scares from either film. Also called The Thing, first-time director Matthijs van Heijningen Jr.’s film credits its source as Who Goes There?, John W. Campbell Jr.’s short story from 1938 that inspired both Carpenter and Hawks’ versions. Although Carpenter kept closer to the source material, here, the screenplay by Eric Heisserer builds on Carpenter’s take. Thus Bill Lancaster’s thirty-year-old script and Carpenter should have received screen credit. At any rate, Van Heijningen’s new film can’t decide if it wants to elaborate on Carpenter’s version or pay homage to it, and that indecision is where the fault lies.

In a way, the result is best compared to Superman Returns and Predators. Both were reboots disguised as sequels to established franchises long out of their prime; both were made by talented filmmakers; both held the originals too dearly and refused to carve out a new mythology for themselves. Van Heijningen’s film has those same problems and more. Although, certainly, credit is due: Van Heijningen and his crew went to great lengths to synch scenes from their film with Carpenter’s, reverse engineering a series of (sometimes inelegant) explanations for what happens in the 1982 film, which followed an American outpost in Antarctica plagued by an alien organism. The new version is about the Norwegian base not far away, and what happens there to eventually drive a Siberian Husky racing into the American camp, followed by two gun-crazed Norwegians in a helicopter trying to kill it. This is where Carpenter’s film begins, and where Van Heijningen’s ends.

After Norwegian researchers find a spacecraft buried in the ice, their team discovers an obscure alien frozen not far from the ship’s location, and they require a paleontologist to help remove it from the block in one piece. They fly down cute American Dr. Kate Lloyd (Mary Elizabeth Winstead) to assist moody head-honcho Dr. Sander Halvorson (Ulrich Thomsen) with the task. And before you can say “quarantine,” Dr. Halvorson has drilled a hole to take a tissue sample and loosened the ice for the beast to break free. A squirmy, slimy CGI baddie bursts from the ice and begins claiming victims early on before it’s torched, and during the pursuant investigation, Dr. Kate learns the alien’s cells are imitating the human cells of its victims, and so anyone in the camp could have been consumed and replaced by an imitation. But who? Not that the creature spends much time hiding in its hosts; this one seems all too willing to expose itself in front of a crowd and cause a flame-thrower fuelled uproar.

To be sure, Van Heijningen has no patience for the slow-burning suspense or quiet paranoia in Carpenter’s carefully paced version; suspicion plays a small role in only one scene, where Dr. Kate finds an admitted neat way to determine who’s an alien mimic. After that, it’s all computer-animated monsters jumping through walls and running full speed in close quarters. Devotees to Carpenter’s version will scoff at the lack of practical makeup effects, originally designed by Rob Bottin. Here, the obvious digital creations stay true to Bottin’s ever-morphing designs, but the energetic CGI monsters don’t feel like they’re from the same universe. Never in Carpenter’s version were there “things” sprinting after humans down hallways; they wanted to finish digesting and hide as quickly as possible. They liked their anonymity. They moved eerily slow like there was a timely organic process at work that had been interrupted, causing a sudden, violent outburst. This incongruity between films feels akin to Star Wars, and how the original films feel slower in comparison to the fast-moving prequels—it’s one of the many problems of the Digital Age of cinema, everything has to be fast. But this was a choice made no doubt in service of modern audiences more accustomed to fast-paced monsters onscreen than organisms that take considerable time to gestate.

Likewise, to make the proceedings easier for American audience’s to swallow, Heisserer’s script assures all but one or two characters can switch from Norwegian to English at any moment, limiting the subtitles at what’s supposed to be a Norwegian camp. As for Winstead… Why, you might ask, does a group of Norwegian scientists need a cute American scientist to assist them? The answer: Because American moviegoers need a cute American actress onscreen to break up the monotony of bearded men (what’s more, Winstead’s hair and makeup people seem to have forgotten the film takes place in 1982). Rising star Joel Edgerton (Warrior) plays an American pilot, who along with his co-pilot Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje have very little to do except provide Dr. Kate with someone to relate to in terms of nationality. The same goes for Eric Christian Olsen playing another American scientist. Of course, Carpenter’s film kept austerity by limiting the all-male cast’s numbers, each character deeply internal, making each of them distinct and every death pronounced. None of that cleverness exists here. More than a dozen characters in all increase the body count of Carpenter’s film, but also make the cast members anonymous victims in many cases. None of them feel tangible, unlike the talented cast from Carpenter’s version (Kurt Russell, Wilford Brimley, Keith David, Donald Moffat, et al.).

To the uninitiated, Van Heijningen’s The Thing might prove entertaining if familiar. Certainly, the director has watched many science-fiction films, and that’s very evident. There’s a hide-from-the-monster-in-a-kitchen sequence recalling Jurassic Park, and the ending aboard the alien spacecraft can’t help but evoke Alien, but even with a flamethrower, Winstead doesn’t hold a candle to Ellen Ripley. To those familiar with Carpenter’s version, the result is not only a disappointment but a misfire in tone and execution, failing to recreate the material with either a full embrace of the original’s unnerving atmosphere or with a single stroke of inspired innovation (as, say, Zack Snyder did with his remake Dawn of the Dead). Aside from his set design, which resembles the Norwegian camp from Carpenter’s film quite well, Van Heijningen’s film fails to grab the audience in any respect. It’s rather like “the thing” itself, an imperfect replication that’s serviceable at first glance, but upon closer inspection, deserves to be torched.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review