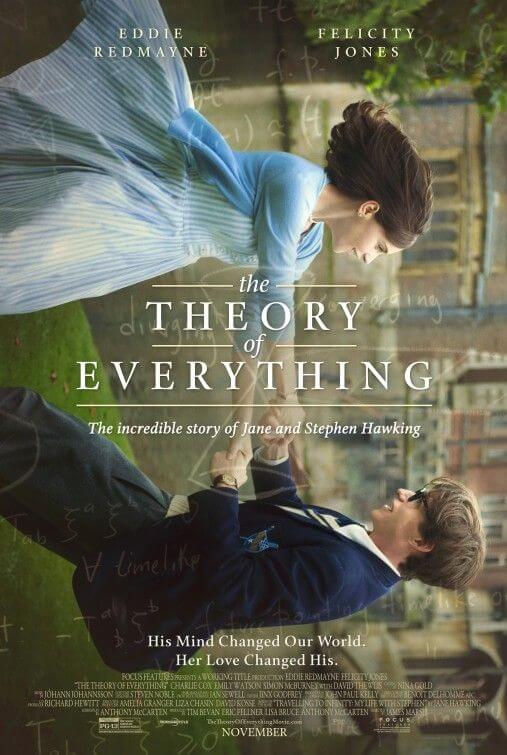

The Theory of Everything

By Brian Eggert |

Biopics that choose a living subject often result in films that fail to adequately engage their topic, and The Theory of Everything is no exception. James Marsh’s film concerns the life of British theoretical physicist and cosmologist Stephen Hawking, a marvelous mind and inspiring man who has overcome much despite physical hindrances—not the least of which is shaping our understanding of the known universe. And while Marsh’s film, based on Jane Hawking’s book Traveling to Infinity: My Life With Stephen, attempts to cover just about everything in Hawking’s life, in its far-reaching approach, it sacrifices much of the dramatic and historical significance of its subject. Most of all, the film is a portrait of a uniquely complicated marriage, and just a little science stuff is added almost as an afterthought.

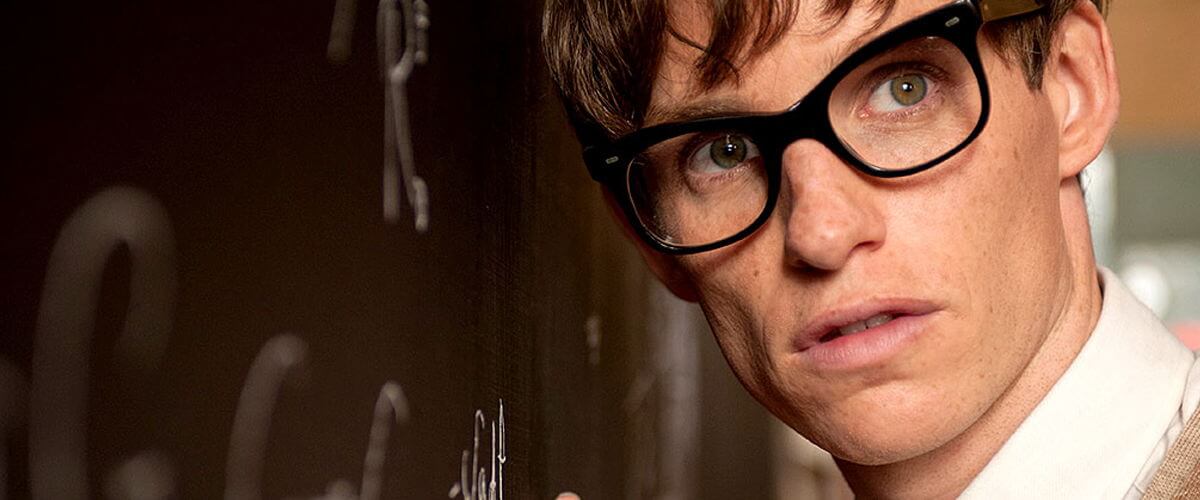

Eddie Redmayne, who looks somewhere between an alien and a thin sheath of skin pulled over a model of the human musculature, gives a transformative performance as Hawking. The actor from My Week with Marilyn and Les Misérables is sure to earn Oscar consideration for his mimicry of Hawking’s distinctive posture and his gradual decline into that state. For those unaware, Hawking suffers from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, better known as Lou Gerhig’s Disease or sometimes motor neuron disease (as it’s called in the film). It’s not quite as dramatic as Locked-in Syndrome (as explored in The Diving Bell and the Butterfly), but it eventually prevented Hawking from moving his body beyond blinks and small gestures with his fingers. Redmayne’s performance remains the prime reason to seek out the film, as he brings Hawking’s descent to vivid physical life.

The film opens in the 1960s when Hawking is studying at Cambridge for his Ph.D. He meets and falls in love with fellow student Jane Wilde (Felicity Jones) through a series of charming, clumsy encounters. Meanwhile, Hawking pins down what he wants to study under the tutelage of his mentor (David Thewlis), which turns out to be the beginning of the universe. At the same time, Hawking discovers his physical malady, and he’s told to expect only another 2 years of life. During that time, he marries Jane, has a child (their first of three), and after earning his Ph.D., shocks the intellectual community with his theories, which are never investigated in much detail (more on that in a moment). As Hawking outlives his prognosis, and he and Jane grow older, the strain of their marriage leads Jane into the arms of a helpful choir instructor (Charlie Cox) and Hawking toward his saucy care assistant (Maxine Peake).

As a documentary filmmaker of Man on Wire and Project Nim, Marsh has demonstrated that he has a skilled approach to combining informative stories in exciting or accessible ways. However, The Theory of Everything washes over the significance and even revolutionary nature of Hawking’s theories by showing us brief shots of an equation on a chalkboard or showing us reactionaries in the scientific community who believe Hawking’s ideas to be rubbish. Hawking’s influence has been taken for granted here, and those not in the know will be left questioning why his mark was so boldly made. Indeed, Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar delves into Hawking’s theories more thoroughly than this film and seems to understand his philosophies and overall vision of the future of the human race better than Anthony McCarten’s exceedingly saccharine screenplay.

In place of any meaningful discussion of relativistic and quantum mechanics (which Errol Morris managed to simplify in his 1992 documentary A Brief History of Time), the film pulls on our heartstrings with a tale of a struggling marriage that eventually ends. As to the point of the drama, beyond appreciating Hawking’s life and Jane’s eventual emotional fulfillment from a safe distance, The Theory of Everything leaves much to be desired in terms of audience satisfaction and a full exploration of a life, not to mention two of them. Never completely about their marriage and never fully about Hawking’s achievements, the film tries to include everything but misses the larger significance of making a consumable, award-friendly film. Nevertheless, Redmayne’s physical performance astounds, and Jones makes a wonderfully empathetic female lead. If only their performances were part of a better treatment of this worthy subject.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review