The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3

By Brian Eggert |

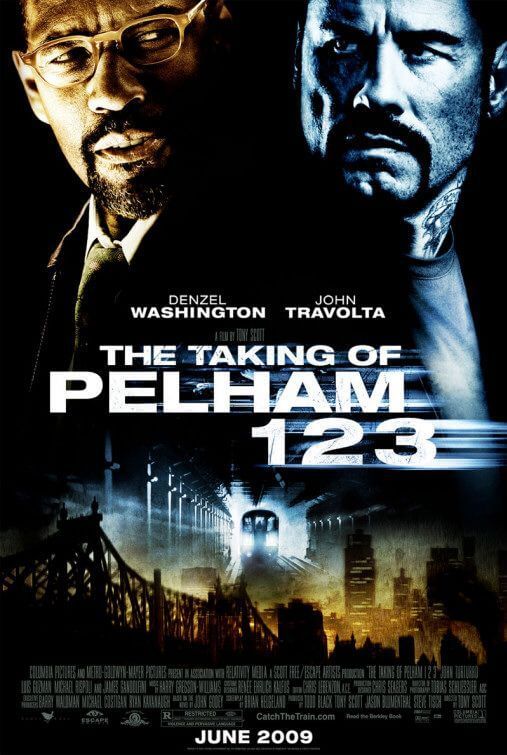

Gone are the days when a thriller about hijackers and the negotiator-hero who stops them feels fresh or necessary. At least, that’s how I felt after The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3, director Tony Scott’s mediocre remake of the 1974 original, based on the novel by John Godey. This by-the-book adaptation introduces a few minor twists into the material and spices up the central characters, but ultimately, it fails to be anything beyond your usual, unnecessary Hollywood do-over.

Another in his long line of actioners led by an everyman hero (see The Last Boy Scout, Enemy of the State, True Romance, et al.), director Tony Scott once again casts Denzel Washington as his leading man. This time, in their fourth collaboration, Washington stars as Walter Garber, a New York City subway traffic controller who answers the call when a group of hijackers takes over a subway train and asks for a ransom of $10 million. Ryder (John Travolta, behind a silly handlebar mustache) leads the band of terrorists (who insist they’re not terrorists at all) in one of those hammy movie villain roles that’s pointlessly over-the-top, complete with wild, unmotivated outbursts and gratuitous uses of the F-word.

Ryder gives a deadline of one hour, and the befuddled Garber does his best-playing hostage negotiator to stall, while The Mayor (James Gandolfini) scrambles to organize the drop-off. And for once, the Mayor character doesn’t harp about his upcoming election or what the voters will think. Quite the opposite. The character mentions his term is up in nine months and couldn’t care less about votes. While the complete opposite of the cliché is just as obvious as the cliché itself, it’s refreshing to know the filmmakers thought to avoid it.

The NYPD’s actual hostage negotiator (John Turturro) coaches Garber from behind the scenes, nodding and writing down talking points for our hero. Like every movie hostage negotiation, Garber and Ryder enter into a preposterous bond where, through a confessional-style conversation, they realize that they’re not all that different from one another. Within minutes of their initial banter, the script, written by Brian Helgeland (L.A. Confidential), has Ryder boasting that they’re the same and that their meeting is fate. Then Ryder prattles on about his Catholic guilt, Garber makes some admissions of his own, and the story continues as though nothing happened. Meanwhile, we feel like we’re being pressured into buying a connection between these two men that simply isn’t there.

In the original, Walter Matthau played Garber as a cop, whereas the new movie goes to great lengths to show Washington could be you or me. There’s a whole backstory about the new Garber, complete with character-defining flaws that are ultimately superficial at best. Washington’s affable presence makes up for his character’s generic description, but even his geniality feels cheesy when the final frame freezes on him, like the last shot of a sitcom. Opposite Matthau, Robert Shaw played the head hijacker as a cold and calculating, if not robotic, ex-mercenary. Travolta is allowed to develop a personality, but he’s utterly annoying during his forced rants about how The System and Bureaucracy have given everyone a raw deal.

The scheme is sort of silly today, particularly when you consider how stupid it would be to hijack a subway train in NYC. Aren’t there better, smarter ways to amass a ransom? Wouldn’t this city, in particular, be (perhaps overly) prepared to respond to criminal terrorist actions, given its recent history? This film’s NYC has become a kinder, gentler metropolis, thankfully devoid of those laughable stereotypes present in the original: The Mayor isn’t a bawling goon, the hostages aren’t racial profiles, and the general negativity of the urban sprawl doesn’t inhabit every scene. At one point, Travolta announces that NYC “is the biggest rathole in the world.” That description hasn’t been true since Jason Takes Manhattan.

Scott forgoes some aspects of his usual overloaded post-modern stylization. He leaves his fast-paced cutting on the wayside, though the swooshing camera movements remain. There’s none of those pointless flash-jumps like in Scott’s Man on Fire, and not too many speed-ups or slow-downs. But the slow-motion is that hazy type that looks like you’ve opened your eyes underwater. A countdown meter bursts onto the screen occasionally, and you might remember a similar device from Scott’s Spy Game. It’s meant to create suspense, except, there’s not much suspense to be found here.

Diverting enough in the second act to keep you from checking your watch, the final act goes melodramatic to eye-rolling extremes. And with plot holes and inconsistencies so abundant that they’ll drive an attentive viewer mad, the sloppiness of Helgeland’s script suggests it was the second draft, and that it probably needed a third and fourth. That the production found two bankable stars, a hit director, and known material to advertise was probably enough for producers to avoid paying for another draft or a complete rewrite. And so, in true Hollywood remake fashion, audiences are left to endure some obviously lazy storytelling.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review