The Tailor of Panama

By Brian Eggert |

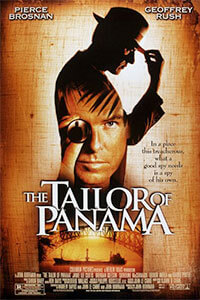

John Boorman’s 2001 take on The Tailor of Panama blends an odd sense of whimsy with the labyrinthine plot you would expect from John le Carré. The 1996 novel tracks a complicated spy scenario in post-Noriega Panama and, in novelistic fashion, takes us inside the heads of its characters in a way the adaptation (authored by Le Carré, Boorman, and Andrew Davies) fails to replicate. The resulting film about a British tailor enlisted by a sleazy MI:6 agent to provide insider secrets boasts several compelling characters realized through strong performances (Geoffrey Rush fresh off an Oscar win; Pierce Brosnan, still in his good graces with the James Bond franchise), but it plays like a narrative mess of confused perspectives and inconsistent, sometimes random techniques. Moreover, Le Carré draws heavily from Graham Greene’s 1958 book Our Man in Havana, already turned into an excellent film in the subsequent year by Carol Reed, in that both take a darkly comic look at British expatriates who cook up elaborate falsehoods to feed to their controllers, and in effect, deliciously critique British and U.S. nationalism in the post-colonial world.

Set in modern-day Panama, a place one character calls “Casablanca without heroes” (which won’t be the last reference to that classic), the film opens with British agent Andy Osnard (Brosnan) being punished for his misdeeds—seducing women on the job, a detail that winks at an audience familiar with Brosnan’s role as Ian Fleming’s womanizing master spy James Bond throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. Arriving in Panama, Osnard searches for an informant to squeeze, locating Harry Pendel (Rush), a local tailor with a near-bankrupt shop. Harry puts on airs, telling grandiose stories of his days on Saville Row with his former partner, Uncle Benny (Harold Pinter). But Osnard sees through the bullshit, leveraging his knowledge that Harry was imprisoned and served his time for arson. In exchange for payoffs, Harry introduces the agent to local underground figures in a “silent opposition” that, through implication, is not as quiet as it sounds—Harry’s assistant, Marta (Leonor Varela), and his wreck-of-a-friend Mickey (Brendan Gleeson, struggling to hide his Irish accent under a Panamanian brogue), play heavily into his fiction. Osnard thinks he’s onto something that could restore his good graces, but he’s been deceived by a warped personality.

Harry, happily married to his American wife, Louisa (Jamie Lee Curtis), with whom he has two children (one of them Daniel Radcliffe, the other Boorman’s daughter Lola), creates a series of lies to support his friends and personal financial woes. All of Harry’s friends have a history of political action and rebellion against dogmatic regimes, but they seem wasted now. The inhumanity of the Noriega era in Panama seems to have left psychological scars on Harry, in that he can no longer help himself but create fabrications. His mind has been fractured from suppressing his sordid past for so long that he’s now greeted by hallucinatory phantoms of Uncle Benny, who, despite being a figment of Harry’s imagination, urges him to stop tailoring stories to Osnard. Rush is excellent at being fascinatingly broken—a simple family man and working professional but, like a spy, he carries with him untold secrets.

Equally complicated is Osnard, a self-serving spy desperately trying to prove to his superior (David Hayman) that he’s worthy of a better assignment, except Osnard hardly changes his ways. He’s a walking hunk of sexual machismo who makes lewd remarks (such as “it’s tight from lack of use”) to women he deems frigid and gets handsy with Harry’s wife. He arranges a no-strings-attached exchange with an attractive colleague at the British Embassy, Francesca (Catherine McCormack), frequents the local whorehouses, and in one scene forces Harry into a gay nightclub for a dance. Indeed, Osnard’s near-pansexuality feeds the strain of sordid behavior running through The Tailor of Panama that reflects the U.S. and British myth that Latin America is a hotbed of sexuality. Watching Brosnan in the role, it’s evident that his talent has been curtailed by the Bond franchise, and through Osnard, plays an unhinged and cynical version of the same character, minus the silencer. Inevitably, Osnard figures out he’s been duped by Harry, but the slick agent maneuvers his way around international intrigue, double-crosses, and a scheme involving the U.S. takeover of the Panama Canal—a mission spearheaded by a manic-eyed American general (Dylan Baker), who of course believes God supports the imperialism of the United States.

Equally complicated is Osnard, a self-serving spy desperately trying to prove to his superior (David Hayman) that he’s worthy of a better assignment, except Osnard hardly changes his ways. He’s a walking hunk of sexual machismo who makes lewd remarks (such as “it’s tight from lack of use”) to women he deems frigid and gets handsy with Harry’s wife. He arranges a no-strings-attached exchange with an attractive colleague at the British Embassy, Francesca (Catherine McCormack), frequents the local whorehouses, and in one scene forces Harry into a gay nightclub for a dance. Indeed, Osnard’s near-pansexuality feeds the strain of sordid behavior running through The Tailor of Panama that reflects the U.S. and British myth that Latin America is a hotbed of sexuality. Watching Brosnan in the role, it’s evident that his talent has been curtailed by the Bond franchise, and through Osnard, plays an unhinged and cynical version of the same character, minus the silencer. Inevitably, Osnard figures out he’s been duped by Harry, but the slick agent maneuvers his way around international intrigue, double-crosses, and a scheme involving the U.S. takeover of the Panama Canal—a mission spearheaded by a manic-eyed American general (Dylan Baker), who of course believes God supports the imperialism of the United States.

Boorman’s direction is uncharacteristically haphazard and tonally quite uneven given the nature of the story. The trouble is less Boorman’s than a sloppy screenplay that offers too many methods of communicating information to the viewer—whereas, these disparate elements would seem less incohesive in novel form. There’s plain narrative information delivered in a straightforward manner, but The Tailor of Panama also employs titles that briefly explain the history of Panama, voiceover from Harry, dream sequences, memory flashbacks, and phantom appearances by Pinter as Uncle Benny (sometimes as a voice in Harry’s head, and other times he appears to Harry as a hallucination). In scenes where Harry interacts with Uncle Benny, other characters cannot see him speaking to no one at all, nor do they notice him pausing as the scene plays out in his head, suggesting the exchanges occur in a split-second of mental time. Given the narrative’s myriad of daydreams, dreams, hallucinations, histories, lies, and realities, the layers of the story may be reflected by Boorman’s representational choices, but that doesn’t make the experience any easier to connect with. Along with le Carré’s typical resistance to heroes, the various perspectives in the film overwhelm. Meanwhile, both Rush and Brosnan are heroes of their own story, competing for the audience’s sympathy, though neither receive it, not completely.

Le Carré once admitted that Greene’s Our Man in Havana was an influence on his novel, and certainly Boorman’s film bears an unquestionable resemblance to Reed’s. In the 1959 film, Alec Guinness played Wormold, a vacuum cleaner salesman enlisted by Noel Coward’s Hawthorne, himself a stuffy and lousy spy. Although Osnard proves sharper than Hawthorne, the similarities between Wormold and Harry cannot be underemphasized. Both men have money problems, Wormold in supporting his daughter’s ritzy lifestyle, Harry in a past-due property he’s been secretly keeping up with his wife’s inheritance. Both men tell their controllers elaborate lies to achieve self-serving ends, but also because Wormold enjoys the performative act, while Harry cannot help himself. Both men transition the material from a dark comedy into a grim tale about the harsh realities of contemporary espionage, complete with political unrest, police violence, and corrupt officials that curiously echo the made up stories being told. Harry ultimately has more of a moral center than Wormold, even though his character seems more scattershot, in part due to the erratic use of perspectives and dreams employed by Boorman.

If The Tailor of Panama has anything else in common with the films of yesteryear, it’s the production’s use of white actors in non-white roles. Gleeson, Martin Ferrero, and John Polito play Panamanians under browned skin and distractingly bad accents, which seems surprising for a 2001 release, and ironic given the film’s critique of Western imperialism. Even so, there’s much to admire about the film, largely in the characters created by Rush and Brosnan. The screenplay boasts rich, complicated dialogue, and their exchanges allow the two actors to engage in a witty, intricate repartee throughout. Where the material falters, at least in terms of its story, is the finale, which suggests that major political and military incursions would be swayed by unproven intelligence, thus stretching our suspension of disbelief. It’s believable that Osnard or a few others would be fooled by Harry’s lies given their intimate acquaintance, but under scrutiny, would governments take his word? Along with the erratic perspectives and voices throughout the film, le Carré’s homage to Greene becomes absurdist and far too inconsistently playful in Boorman’s hands. Smart and challenging though it may be at times, The Tailor of Panama remains fragmented in unsatisfying ways.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review