The Stranger

By Brian Eggert |

Orson Welles felt The Stranger was his own worst film. Released in 1946, it was made, in part, to prove to Hollywood that Welles could be profitable after his string of financial disappointments at RKO, and to live up to his promise and reputation as the wunderkind of the Mercury Theater. Needing a payday, Welles resolved to work within the constraints of a melodramatic Hollywood thriller and, in the years to come, he maintained some animosity toward the film because it meant he had sold out. But it proved, for the first and only time in Welles’ career, that the director could conform to Hollywood expectations and deliver a financial success. Given the impetus of the project, it certainly registers as more conventional than other films by the maverick auteur, whose works often look and feel like they were made by a Hollywood outsider (they were). And so, he remained The Stranger’s harshest critic, although critics and historians have since reassessed the film as more unorthodox than it may have initially seemed. If The Stranger’s virtuoso camerawork and frantic pacing, both of which were atypical when compared to the traditional studio style, were not enough to demonstrate that it’s more than a standard thriller of the era, then consider how Welles deals with the Holocaust not only to reinforce his pronounced anti-Nazism, but to engage in a passionate display of political filmmaking that balances activism with entertainment value.

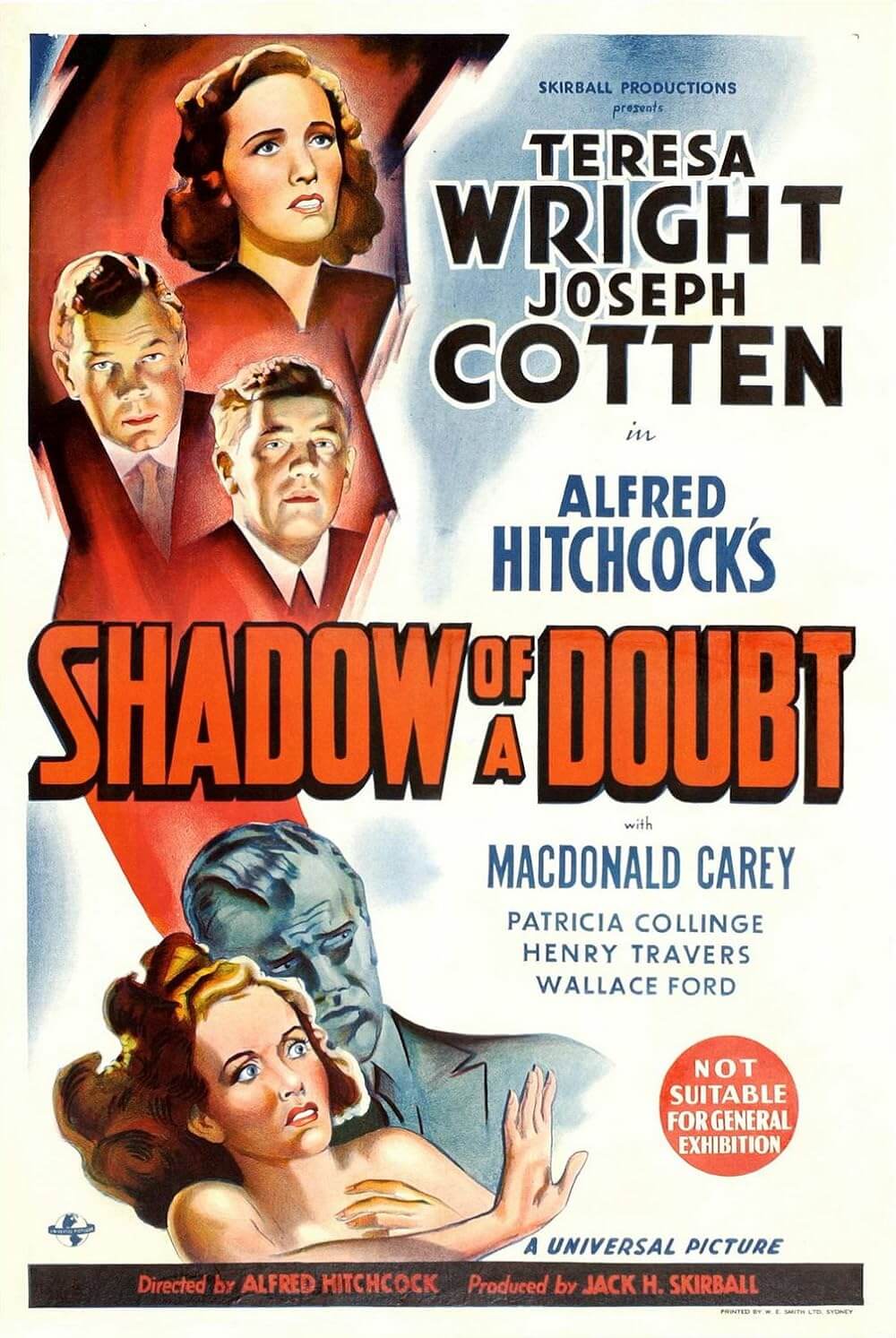

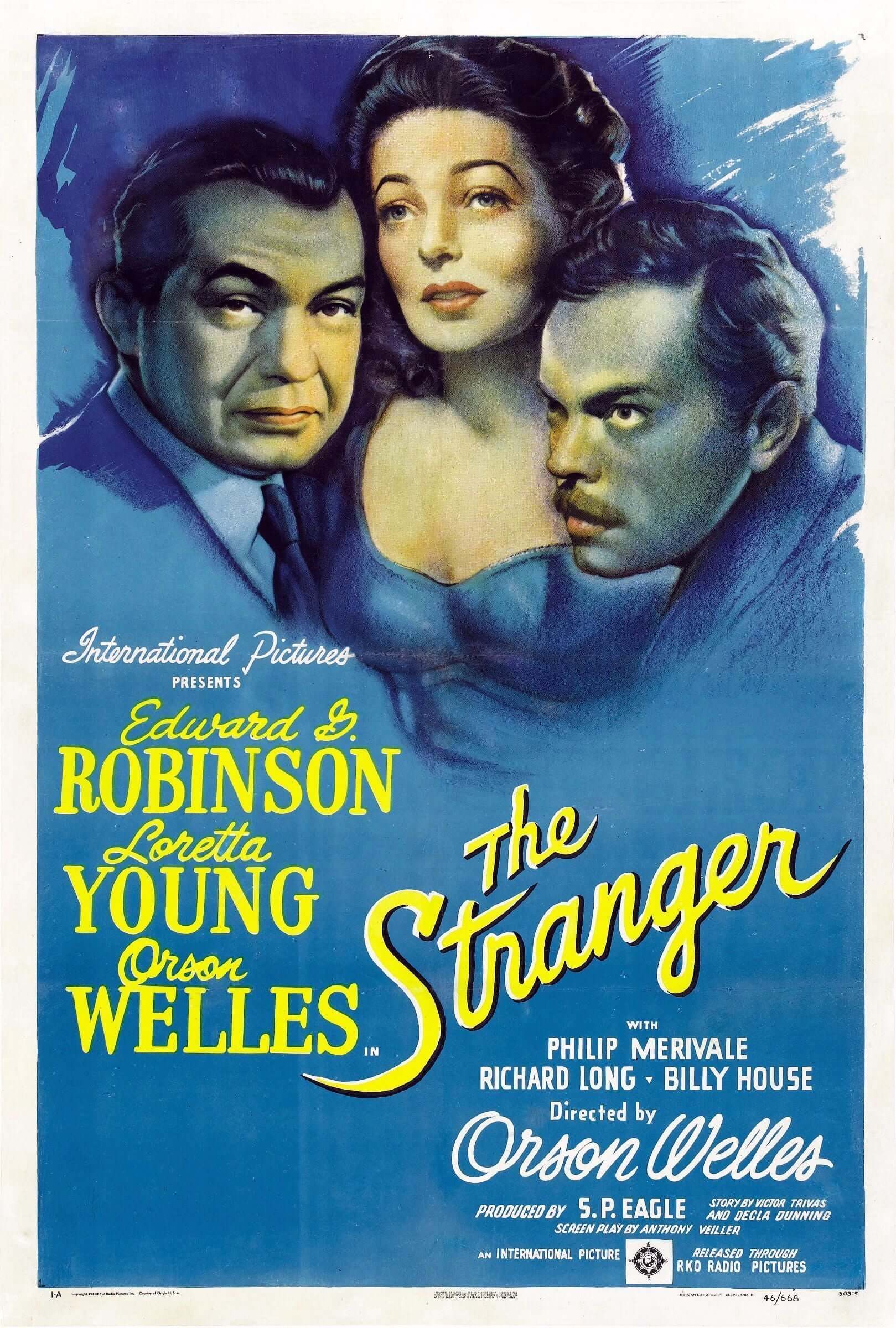

Welles plays a Nazi named Franz Kindler who, after the end of the Second World War, has escaped to the United States and lays low in a small Connecticut town under the name Charles Rankin. Edward G. Robinson costars as Wilson, an agent of the Allied War Crimes Commission hot on Rankin’s trail. The former Nazi has tried to blend in; he teaches at the local school for boys and weds Mary (Loretta Young), the daughter of the town judge. Welles plays Rankin as suspiciously elegant, lending to the idea that anyone anywhere could be the enemy—that incognito Nazis could penetrate even the most inconsequential parts of postwar America. The idea was to destroy the illusion of safety for the average American citizen, something Alfred Hitchcock did successfully three years prior in Shadow of a Doubt (1943). That film brought Joseph Cotten’s Charlie to Santa Rosa, California. The much-loved uncle of a perfect family, Charlie would soon be exposed by his niece as “The Merry Widow Murderer,” thus bringing East Coast criminality to a perfect little piece of West Coast suburbia. It’s been debated by several film historians whether Anthony Veiller’s script for The Stranger was inspired in part by Hitchcock’s film, which Hitchcock considered his personal favorite of his own works.

Producer Sam Spiegel, who at the time was a rookie in Hollywood, pushed for Veiller’s script for The Stranger, based on a story by Victor Trivas, to be financed by International Pictures and distributed by RKO Radio Pictures (the script would eventually be doctored by John Huston). Welles was hired as both director and the film’s villain, but he had only modest input on the script. Made for little more than $1 million, it garnered upwards of $3 million at the box-office in its initial release. Behind the scenes, Hollywood lore tells us Welles shot a long sequence in which a Nazi named Konrad Meinike (Konstantin Shayne) searches for Kindler—some twenty minutes longer than the one that appears in the film, and possibly resembling the dizzying searching-down-a-lead sequences in Welles’ later Mr. Arkadin (1955). But the fate of the longer scene involving Meinike in The Stranger is yet another unfortunate tale from Welles’ storied history in Hollywood, as these twenty minutes of footage were cut by Spiegel and destroyed. Spiegel believed them to off-center given the plot’s centralized location in New England. Welles claimed the sequence was, in his opinion, the most interesting in the film, possibly since it was conceived and written by Welles himself. But then, any account of Welles’ experiences in Hollywood must include dozens of stories about producer interference that reshaped his historically troubled productions.

What remains curious is that no one stopped Welles from using actual footage from the liberation of concentration camps in The Stranger. In the film, Wilson must convince Mary that her husband Rankin is the mastermind of the Holocaust. To accomplish this, he shows Mary a short reel of footage from a concentration camp to illustrate the inhumanity of Nazis. Rather than simply describe the footage or, say, show Mary looking away from the projected footage in horror, Welles resolved to use real-life images—marking the first time a major Hollywood motion picture used actual Holocaust footage. The images are brief and amount to just four quick shots. First is a glimpse of a mass grave filled with bodies, then the interior of an empty gas chamber, a shot of men heading into a chamber, and finally an emaciated victim. The images hardly amount to the visual study of atrocity that Alain Resnais’ Night and Fog (1956) would provide a decade later. But Wilson describes them for Mary, going into terrible detail about how showers opened the pores to make the gas chambers a more effective killing apparatus. Welles acquired the images from documentary footage captured by George Stevens during his wartime experiences in Europe. Stevens’ footage was later assembled into Billy Wilder’s short film for the U.S. War Department, Death Mills (1945), which documented “the worst mass murder in human history” for the education of the German people, according to its titles.

What remains curious is that no one stopped Welles from using actual footage from the liberation of concentration camps in The Stranger. In the film, Wilson must convince Mary that her husband Rankin is the mastermind of the Holocaust. To accomplish this, he shows Mary a short reel of footage from a concentration camp to illustrate the inhumanity of Nazis. Rather than simply describe the footage or, say, show Mary looking away from the projected footage in horror, Welles resolved to use real-life images—marking the first time a major Hollywood motion picture used actual Holocaust footage. The images are brief and amount to just four quick shots. First is a glimpse of a mass grave filled with bodies, then the interior of an empty gas chamber, a shot of men heading into a chamber, and finally an emaciated victim. The images hardly amount to the visual study of atrocity that Alain Resnais’ Night and Fog (1956) would provide a decade later. But Wilson describes them for Mary, going into terrible detail about how showers opened the pores to make the gas chambers a more effective killing apparatus. Welles acquired the images from documentary footage captured by George Stevens during his wartime experiences in Europe. Stevens’ footage was later assembled into Billy Wilder’s short film for the U.S. War Department, Death Mills (1945), which documented “the worst mass murder in human history” for the education of the German people, according to its titles.

Welles’ use of these images implants a sense of veracity yet unseen by the average American, who was just beginning to hear about the extent of the Holocaust during radio broadcasts of the Nuremberg trials. In total, they occupy the screen for no more than a few abrupt seconds. They nevertheless imbue The Stranger with a real-world component that, in 1946, inflamed postwar anxieties about the lingering threat of fascism and the persistent fear among many that the Nazi threat would return—ideas that compelled Welles to agree to make The Stranger in the first place. The horrors of World War II were being uncovered at the time, and footage of concentration camps was suddenly showing up on newsreels. Although Welles uses such images, he claimed in his interviews with Peter Bogdanovich that he doesn’t approve of exploitation of such atrocities for entertainment, even while adding that concentration camp imagery serves to remind people of the horrible truth.

Although he is primarily known as a filmmaker and stage pioneer, Welles flirted with the notion of a career in politics early in his career. He was, after all, every bit as idiosyncratic as Churchill and Roosevelt, whose larger-than-life personalities could sell a political idea better than most. A confident voice like that of Welles, a master orator, could sound off on any number of topics and convince listeners of his perspective. Welles was perhaps too idealistic to enter the cynical realm of Washington, and he set aside any ambitions of becoming a politician in the early 1940s. But he used his platform on American radio beginning in the 1930s to become a critical voice in the Popular Front that stood against fascism. He wrote political articles in the journal Free World and kept a column in the New York Post, often speaking out against fascism abroad and racism at home. The Stranger, then, seems to serve two objectives for Welles: The first demonstrates his bankability and willingness to play the game to Hollywood executives who were otherwise skeptical of this Tinseltown outsider. The second allows Welles to blend his political discourse with the public and his role as a filmmaker. Fortunately, the second objective never obstructs the first.

The Stranger’s sharp use of real-life footage from concentration camps enhances rather than distracts the viewer from the stakes of the film. With just a few moments of footage, Welles legitimizes and elevates an otherwise escapist yarn with real-world consequence. It is shocking how effective the footage is—it shifts Rankin’s presence in the sleepy Connecticut town from that of an average screen killer, who in an early scene strangles Meinike to preserve his own cover, to an orchestrator of mass death that anticipates the return of Nazism. What might have been a relatively standard, albeit expertly directed and acted thriller, with a touch of high emotion courtesy of Young, becomes scarier because we see the consequences. The Holocaust footage is brief enough that it avoids distracting from the narrative thrust or dwelling on the real-life situation. Welles avoids turning it into a soapboxing interlude that could have transformed the film into an outright political statement. Unlike other examples from the period, such as Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940), where a political speech puts the enjoyment of the film on pause for a climactic speech, The Stranger’s use of concentration camp imagery serves rather than diverts from the story. The scene illustrates the truth of the Nazi death camps, and Rankin becomes their face, making his villainous presence all the more insidious.

In late interviews, Welles would continue to dismiss The Stranger, possibly because he had virtually nothing to do with its screen story. David Thompson, author of Rosebud: The Story of Orson Welles, claims that by 1946 Welles had become “bored and artsy” when it came to filmmaking, thus resulting in The Stranger’s un-phenomenal quality of storytelling. One cannot help but disagree with Thompson’s assessment. While it might not have Welles’ typically theatrical dialogue, historical undertones, or use of Shakespearian themes, it does offer crowd-pleasing suspense and the director’s formal bravado. But according to Welles, he was often criticized for the film’s “comic-strip” finale. It ends where a typical thriller might, with the bad guy getting his due and the hero getting his man. But like Hitchcock, even one of Welles’ mediocre films was better than the crowning achievement of another filmmaker’s career. Welles was so astonishingly talented that when placing The Stranger next to his more celebrated work, it’s eclipsed. On its own, however, without taking the entire Welles’ oeuvre into consideration, The Stranger is a worthy thriller.

In late interviews, Welles would continue to dismiss The Stranger, possibly because he had virtually nothing to do with its screen story. David Thompson, author of Rosebud: The Story of Orson Welles, claims that by 1946 Welles had become “bored and artsy” when it came to filmmaking, thus resulting in The Stranger’s un-phenomenal quality of storytelling. One cannot help but disagree with Thompson’s assessment. While it might not have Welles’ typically theatrical dialogue, historical undertones, or use of Shakespearian themes, it does offer crowd-pleasing suspense and the director’s formal bravado. But according to Welles, he was often criticized for the film’s “comic-strip” finale. It ends where a typical thriller might, with the bad guy getting his due and the hero getting his man. But like Hitchcock, even one of Welles’ mediocre films was better than the crowning achievement of another filmmaker’s career. Welles was so astonishingly talented that when placing The Stranger next to his more celebrated work, it’s eclipsed. On its own, however, without taking the entire Welles’ oeuvre into consideration, The Stranger is a worthy thriller.

Welles’ persistent animosity toward The Stranger is understandable from his point of view. It certainly does not spar with traditionalized storytelling formulas, as Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), and many other Welles-directed pictures do. Moreover, The Stranger avoids rethinking story structure or plot coherence, as his later noir pictures like The Lady from Shanghai (1947) or Touch of Evil (1958) do. But the film has other qualities: Welles and Robinson are terrific; the director playfully engages with several odd small-town personalities, bordering on everyday grotesques; and the black-and-white photography by Russell Metty is gorgeous and fluid. Indeed, The Stranger is radical in a different way. Slipping a droplet of the Holocaust’s reality into our standard Hollywood suspenser, Welles allows the viewer to bear witness, even if just for an instant. His daring and impassioned choice brings a vivid urgency to a Hollywood trifle. Without it, The Stranger would still be a compelling film, and we would still be admiring it today. However, Welles sears his film’s place in our minds because he refuses to reduce Nazis to cartoonish movie villains; he reminds us that his story has a potent reality, and he forces us to see it.

(Editor’s Note: This review was expanded and re-edited from a review originally posted on July 23, 2007.)

Sources:

Bazin, André. Orson Welles: a critical view. Foreword by François Truffaut; profile by Jean Cocteau; translated from the French by Jonathan Rosenbaum. New York: Harper & Row, 1978.

Benamou, Catherine L. It’s all true: Orson Welles’s Pan-American Odyssey. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007.

Denning, Michael. The Cultural Front: The Laboring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century. Verso, 1998.

Gilmore, James N., Sidney Gottlieb (editors). Orson Welles in Focus: Texts and Contexts. Indiana University Press, 2018.

Heylin, Clinton. Despite the System: Orson Welles Versus the Hollywood Studios. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2005.

McBride, Joseph. Orson Welles. New York: Da Capo Press, 1996.

Thomson, David. Rosebud: The Story of Orson Welles. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996.

Welles, Orson; Bogdanovich, Peter. This is Orson Welles. Edited by Jonathan Rosenbaum. New York: Da Capo Press, 1998.

Wilson, Kristi M., and Tomás F. Crowder-Taraborrelli (editors). Film and Genocide. The University of Wisconsin Press, 2012.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review