The Stepfather

By Brian Eggert |

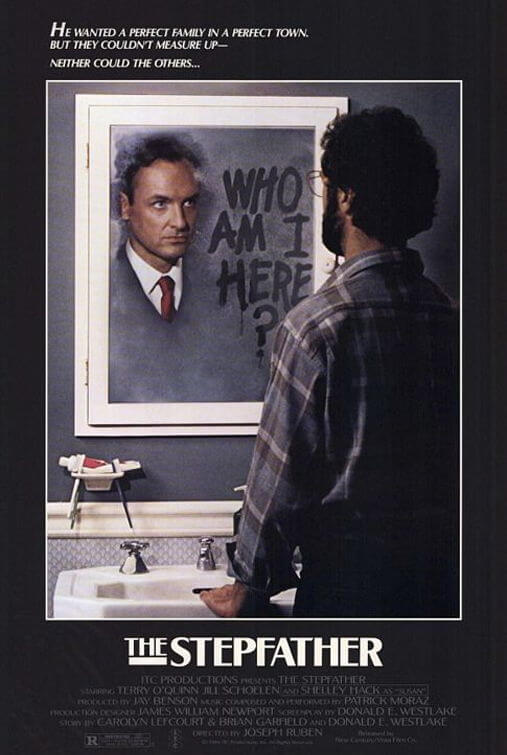

Something of a cult classic, The Stepfather, released in 1987, was made during a time when Hollywood wasn’t afraid to release R-rated horror movies. Most modern genre fodder comes bloodless and with a PG-13 prerequisite, because after all, there are box-office numbers to consider, and young teens love their body count fare. But here’s a movie that represents exactly what ‘80s horror was all about, while also furnishing an (ironically) satisfying experience, unlike its comparatively shoddy 2009 remake.

Terry O’Quinn, best known today as John Locke from TV’s Lost, stars as the eponymous stepfather. He’s a serial killer who marries divorcees or lonely widows with children in search of the American family ideal. Some part of him desperately wants a nuclear family, complete with a strict adherence to old-fashioned principles (passed down by his abusive father, who’s hinted at in the script). He strives to be a providing, prototypical paterfamilias, wearing plaid flannel shirts and busying himself in his tool-lined basement workshop. He seems to be the perfect man to his wives, so charming and helpful. Somewhere down the line, however, his families disappoint him and he cracks.

After leaving the scene of his latest failed family experiment that ends in a bloody mess, he changes his identity and settles down in a sleepy town under the name Jerry Blake. He secures himself a job as a realtor and a place in the home of widow Susan Maine (Shelley Hack) and her teenage daughter Stephanie (Jill Schoelen). He and Susan wed, but Stephanie, who has become a delinquent ever since her father died, remains wary of her stepfather. Something about him just doesn’t seem right. She tries to confirm her misgivings, and she makes a lot of stupid mistakes that double as suspense. A scene where Jerry rants a whole lot of crazy in the basement to blow off some steam becomes wrought with danger; he realizes that Stephanie has been silently observing him. Whoops.

Anyone who suspects Jerry ends up dead, such as Stephanie’s therapist, a nice guy who asks too many questions. There’s a hilarious subplot involving the homemade detective Jim Ogilvie (Stephen Shellen), a relative of Jerry Blake’s former family, now slain. Jim is out for revenge and doing everything his tiny brain can think of to catch the killer. When he eventually gets a jump on his man, his gun gets stuck in his jacket pocket and Jerry stabs him. Too bad for Jim. (Note: The subplot is reminiscent of Scatman Crothers’ role in The Shining. Stanley Kubrick spends a considerable amount of screentime setting up the character’s elaborate return to the haunted hotel to save the little boy, and when he finally arrives to save the day—Thwack!—Jack Nicholson plunges his chest with an axe.)

Never mind the hokey plot and instead focus on O’Quinn. So many movie killers hide behind masks that to have one with a personality is refreshing. There’s nothing supernatural about Jerry Blake. He doesn’t invade your dreams and he’s not impervious to harm. He’s the potential danger hiding behind every human face. What if suddenly your husband or wife referred to themselves by another name, then stopped and said, “Wait, who am I here?” O’Quinn does it with equally frightening yet human expressions, adding needed layers to an otherwise one-note character type. But there’s also an ever-present look of madness behind his eyes that adds an element of hilarity to every scene.

A little bit cheesy, and very bloody, but made with a wry sense of humor by director Joseph Ruben, The Stepfather cannot be watched without a sense of mockery. Sinister lines like “You’ve been a bad, bad girl” aren’t meant to be taken seriously, and their camp value keeps home viewings alive with plentiful hooting laughter. But more than other cornball horror movies from this era, the movie proves to be an involving thriller, primarily because of O’Quinn’s menacing performance. The suspense is rather typical and formulated, but it’s diverting entertainment, even if it is trash. Still, the lesson about the American family is penetrating. An idealized family unit proves so impossible to achieve that drives Jerry to psychosis. It’s at once a sharp commentary and a frightening statement.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review