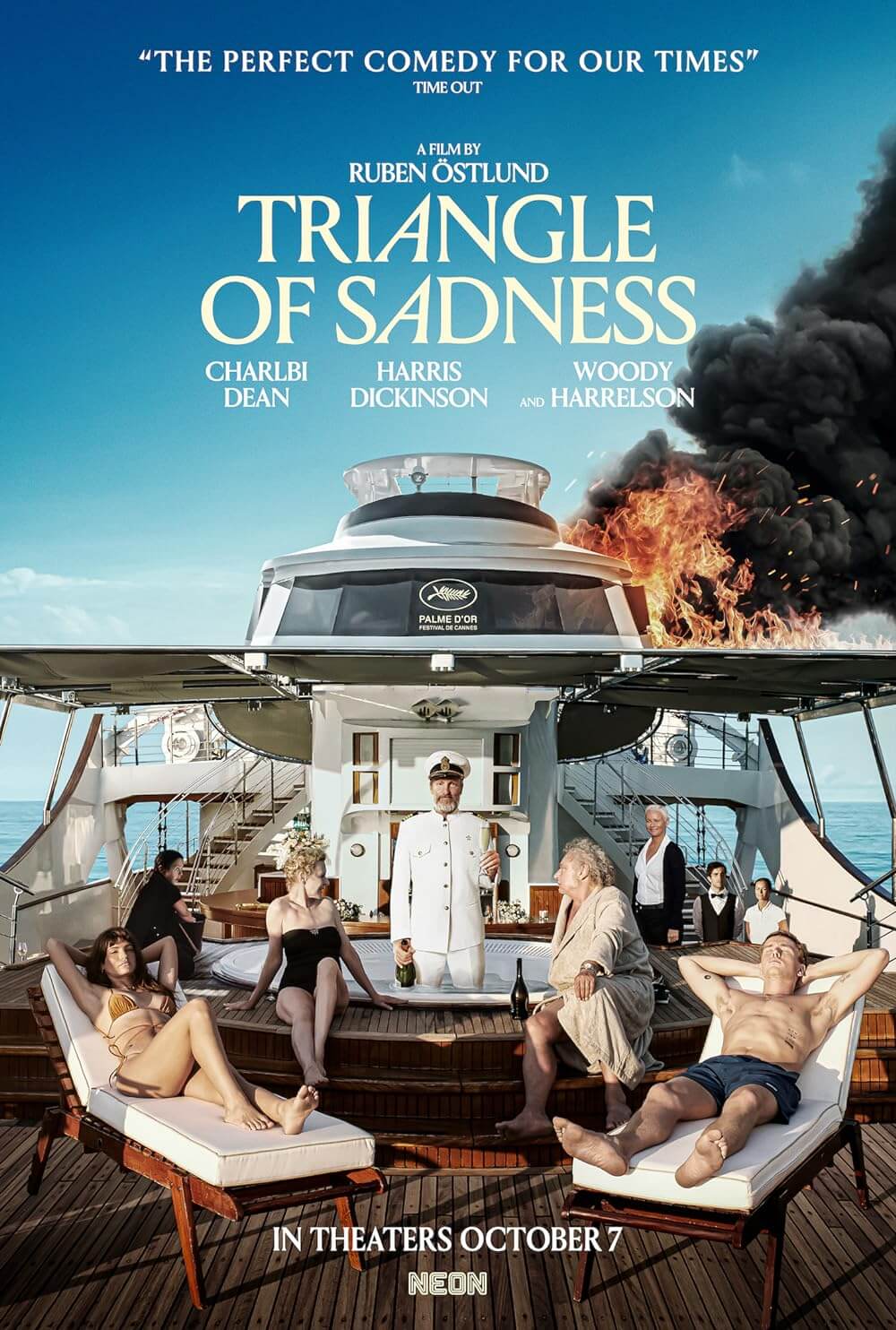

The Square

By Brian Eggert |

A crucial moment in Ruben Östlund’s The Square involves a woman screaming for help in a crowd. While most of the pedestrians around Christian, an art curator at a progressive museum of contemporary art, keep walking, oblivious to her pleas, he hears the cries and looks around, concerned. All at once, the woman races toward Christian and another male bystander, screaming in terror about someone chasing her with the intent to harm. The bystander, a muscular sort, directs the woman behind him and gives Christian a look of obligation to stand near and protect the woman. Reluctantly, Christian complies. Together, they brace for the worst as, from off in the distance, an enraged male voice comes charging toward them. Evidently a couple in the midst of a heated spat, the pursued woman and her angered beau shout at each other until the bystander and Christian convince them to go their separate ways. After the scene settles, the two heroes of the moment congratulate each other, their hearts pumping, their egos satiated by their masculine performance. Shortly after the encounter, Christian realizes he has been robbed; the entire scene was staged like a work of performance art. Demasculated by deft con artists, Christian feels powerless, as he does again and again throughout Östlund’s satirical comic epic of human selfishness, modern art, and troubled conscience.

A genius observer of insecurities and disingenuous behavior, Östlund points his crosshairs at a broad target in The Square, at least compared to his more streamlined 2014 effort, Force Majeure. That film was a small masterpiece about deconstructing gender roles, specifically the vulnerable male ego, parental defense mechanisms, and survival instincts. In Force Majeure, a father darts away from his family in a life-or-death situation; and while everyone proves just fine, his identity receives a severe blow. The Square, not to be confused with Nash Edgerton’s intense neo-noir of the same name, offers a series of confronting tableaus that strike at any number of moving targets—above all, the social justice warriors and liberal elite that pronounce their devotion to a cause with a check or disengaged online activism, as opposed to actual activism. For all the enlightenment of the left-minded progressives, Östlund presents a scene to take them down a notch, yet never without a feeling of empathy or outrageous humor.

To this end, Christian (Claes Bang, excellent), a smooth operator on the exterior, a self-conscious and cowardly type elsewhere, remains the perfect protagonist who alternates between craven power and utter cluelessness. Christian often finds himself involved in helping strangers; however, he’s not far from a Swedish version of Larry David, always causing a series of unintended disasters whenever he tries to correct his mistakes. Early on, his assistant (Christopher Laessø) convinces him to take action to recover his pickpocketed wallet and smartphone. He tracks his stolen phone to an apartment complex in what he believes to be a bad neighborhood; there, in a juvenile plan, he proceeds to leave a note in every mailbox, hoping to scare the thieves into returning his stolen items. His impatience with and attitude towards the people living in the building have unfortunate consequences for a young boy (Elijandro Edouard), an insistent symbol of Christian’s social negligence and, by the end, inability to act responsibly, with disturbing results.

However oblivious-but-well-meaning Christian may seem, his attitude toward women punishes him and remains undeniably petty. Enter Anne (Elisabeth Moss), a journalist who interviews Christian and, not long afterward, sleeps with him. Christian openly admits he takes advantage of his position to savor casual sexual encounters with his female admirers, but that doesn’t make him any less sympathetic in a scene inside Anne’s apartment that digresses into madness. It begins with Christian admiring some drawings on the floor, until he soon realizes the scribbles belong to Anne’s full-grown pet ape, which scuttles into the next room unannounced, a matter that is never adequately explained, adding to the comic confusion. After sex, Anne’s behavior toward the used condom proves achingly bizarre and downright cryptic, hilariously so. But her confrontation of Christian days later, in a nightmare scenario for any promiscuous male, reminds the viewer that he’s no saint, and there’s a certain joy in watching him squirm.

The film’s title refers to an exhibit etched into the cobblestone outside of the X-Royal, a (fictional) former residence of Swedish royalty in Stockholm that has since been reconfigured into a modern art museum. Measuring four-by-four meters, a square space is illuminated by a simple white neon line, and preceded by a plaque reading, “The Square is a sanctuary of trust and caring. Within it we all share equal rights and obligations.” The idea, as Christian explains it, suggests that anyone standing inside of this space cannot be ignored. Should they ask for change, anyone outside of the square must comply; should they ask for time to talk about something bothering them, someone outside of the square must devote the time. A rather simplistic (yet admittedly endearing) idea to promote compassion and good-Samaritanism, The Square remains a bland promotional nightmare for the museum’s marketing company. The eventual timebomb-of-a-campaign designed to promote the exhibit proves unforgettable (asking the question, “How much inhumanity does it take before we access your humanity?”), and through it, Östlund questions what draws more attention from viewers today: marketing or art. Do more people react to marketing campaigns or high art, to trailers or to actual films? And what does that say about the audience and their declining attention spans, not to mention the relevance of art?

Another theme permeating throughout falls on the homeless, and how the self-righteous art crowds celebrate high humanitarian art but remain ignorant and downright cruel toward the living subjects of the art they so adore. Whether Östlund takes a few moments to start a new day with a series of shots depicting beggars on the street, or he considers neglected people through an entire subplot, the homeless and their relationship to Christian’s self-obsessed world remains a persistent undercurrent in The Square. Take a sequence in which Christian enters a 7-Eleven and is confronted by a homeless woman. She asks him for some change but he has nothing to give; he offers to buy her something to eat instead. “Chicken ciabatta,” she requests. “And no onions.” Christian reacts with incredulity. And while this moment might seem like a lesson in not looking a gift horse in the mouth, or beggers can’t be choosers, it’s another lesson entirely. After all, dehumanizing homeless people makes ignoring them much easier. But when confronted with their basic human tastes and desires, even as simple as preferring no onions on a chicken ciabatta sandwich, then their social status and humanity becomes impossible to disregard, and therefore inconvenient.

The Square can feel episodic at times, delivering into a vignette-style skewering of familiar and apathetic behaviors within a single sequence. The best of them involves the museum’s posh fundraising event in which a performance artist, named Oleg (played by Terry Notary, a motion-capture artist in several ape roles from Rise of the Planet of the Apes to Kong: Skull Island), stalks the well-dressed attendees in the role of a wild ape. It doesn’t take long for most to keep their heads down and avoid eye contact with the shirtless simian-human, as the alternating levels of comedy and terror bring the evening to a standstill. Several guests opt to leave the room from discomfort over Oleg’s whooping and screeching. Then, in a moment drawing from the same surreal pitch as Luis Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel (1967), Oleg takes the performance too far. Part of the tension, and joy, of the scene involves wondering how long it will take for the guests to interrupt the performance. When they do, the reaction proves anything but apathetic. It may be the single best scene in any film in 2017. And each major sequence like this is bridged by transitional gags, such as a floor sweeper who must carefully navigate through an installation comprised of carefully situated piles of granite, a Tourette’s afflicted audience member at an artist’s lecture, or even less comic moments, like portraits of the homeless throughout Stockholm.

The Square can feel episodic at times, delivering into a vignette-style skewering of familiar and apathetic behaviors within a single sequence. The best of them involves the museum’s posh fundraising event in which a performance artist, named Oleg (played by Terry Notary, a motion-capture artist in several ape roles from Rise of the Planet of the Apes to Kong: Skull Island), stalks the well-dressed attendees in the role of a wild ape. It doesn’t take long for most to keep their heads down and avoid eye contact with the shirtless simian-human, as the alternating levels of comedy and terror bring the evening to a standstill. Several guests opt to leave the room from discomfort over Oleg’s whooping and screeching. Then, in a moment drawing from the same surreal pitch as Luis Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel (1967), Oleg takes the performance too far. Part of the tension, and joy, of the scene involves wondering how long it will take for the guests to interrupt the performance. When they do, the reaction proves anything but apathetic. It may be the single best scene in any film in 2017. And each major sequence like this is bridged by transitional gags, such as a floor sweeper who must carefully navigate through an installation comprised of carefully situated piles of granite, a Tourette’s afflicted audience member at an artist’s lecture, or even less comic moments, like portraits of the homeless throughout Stockholm.

Formally, Östlund’s reserved aesthetic choices offer a museum-like presentation, where each passage is presented from wide- or medium-length shots composed with beautiful clarity by cinematographer Fredrik Wetzel. Several sequences, like those discussed in detail above, could serve as short films or museum pieces unto themselves—some of them rooted in sophisticated humor, others comprised of trenchant insight on the shallowness of humanity. Against it all, Östlund uses music from voices like Bobby McFerring, classical works by Bach, and the infectious burst of energy provided with “Genesis” by electronica group Justice. Östlund, who also wrote the script and exhibited a real-world version of The Square (he’s also divorced with two daughters, like Christian, suggesting the entire film may be about Östlund making fun of himself), steeps his film in sight gags and ponderous commentary. Though, admittedly, it’s difficult to succinctly describe what The Square is “about”—and any such attempt could lead to a number of conversations, each feeding into a larger whole. Perhaps that’s what makes it great.

Over its 142-minute runtime, a length that implies its scope and import, the film resembles Michael Haneke’s penetrating Code Unknown (2000), a superior work that considers why people insert themselves into the lives of others, or why they refuse to get involved. With that in mind, The Square presents a focused view on a microcosmic division of society to address more universal themes. Both wildly entertaining and shrewd in its study of human behavior, Östlund’s film ruminates on a lot of things: the nature of art and expression, the abuse of patriarchal powers, what it means to participate in humanity, and the illusion of class difference. Reactions to the film have certainly been divisive: it won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in May 2017, whereas many critics have called the film “pretentious” or “didactic” as an insult to its searching. Sharpened by a series of corrosive comic moments and provocations, The Square lashes out with a refined blow against both indifference and empty gestures of faux-humanitarianism, delivering the funniest and most artistically made comedy since The Lobster (2016) or, well, Östlund’s last film.

If You Value Independent Film Criticism, Support It

Quality written film criticism is becoming increasingly rare. If the writing here has enriched your experience with movies, consider giving back through Patreon. Your support makes future reviews and essays possible, while providing you with exclusive access to original work and a dedicated community of readers. Consider making a one-time donation, joining Patreon, or showing your support in other ways.

Thanks for reading!

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review