The Sparks Brothers

By Brian Eggert |

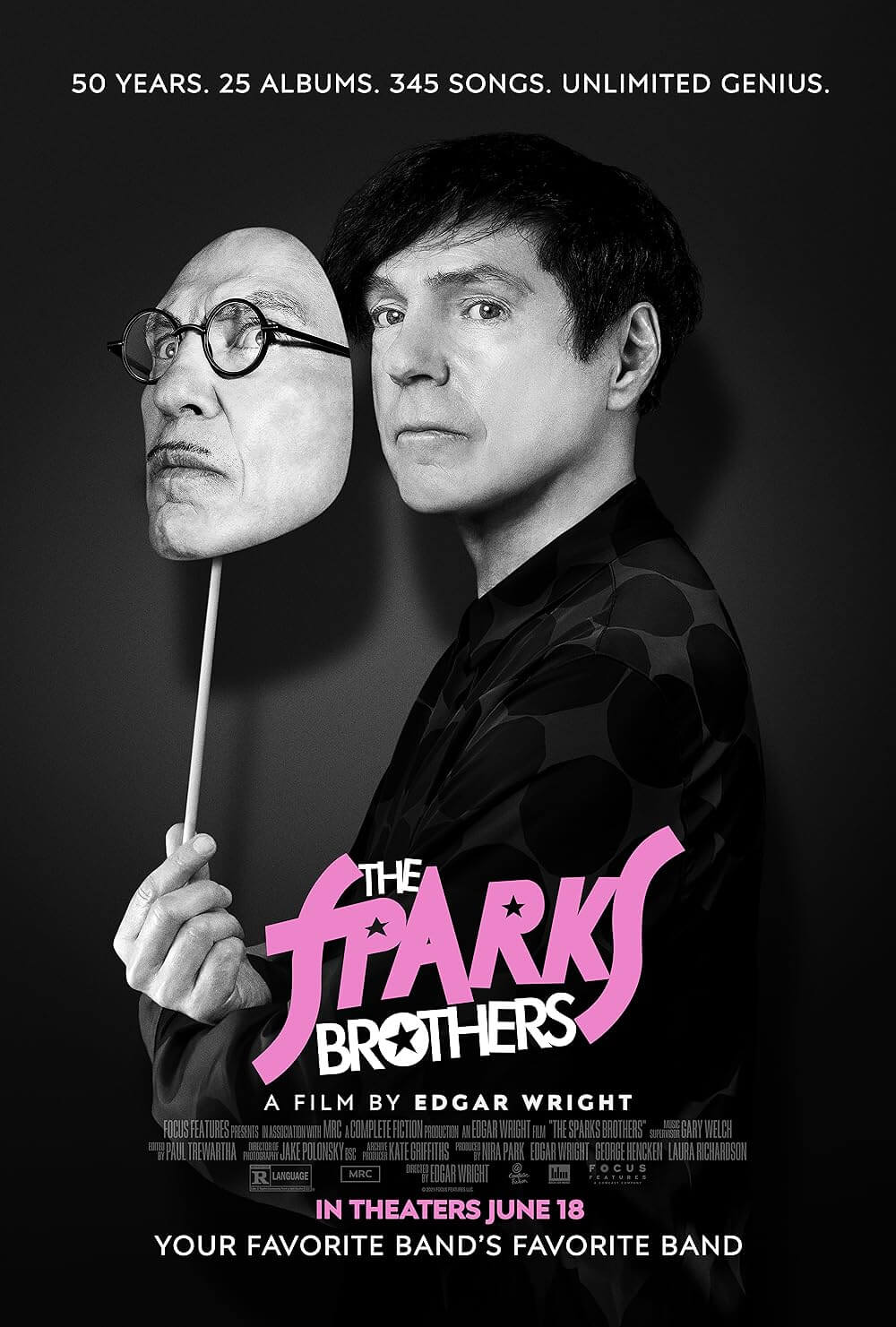

Director Edgar Wright asks how can Sparks, an unclassifiable music duo created by Ron and Russell Mael, which has been around for 50 years, “be successful, underrated, hugely influential, and overlooked, all at the same time?” Wright’s lovingly made documentary The Sparks Brothers sets out to answer that question, using conventional methods of talking head interviews, various animation styles, and archival footage. It’s an approach you’ve seen in countless other Behind the Music-style docs before, but rarely with such enthusiasm or personal connection between the filmmaker and subject. A superfan, Wright delves into the Maels’ life and career, cracking and peeling away at the enigmatic shell to get at the good stuff inside. Well, some of it anyway. They keep redefining themselves, and their only constant is refusing to be placed in a box. The doc may not give the cultish fanbase new insights; however, it introduces the unversed to their favorite new band (which has been around since the late 1960s).

Admittedly, I had only peripheral knowledge of Sparks before the film, and thus I was probably Wright’s ideal viewer: someone who likes British rock and pop from yesteryear, including David Bowie, The Kinks, and The Who; someone who obsesses over new wave and post-punk, such as New Order, Devo, and Talking Heads; someone who generally prefers the modern indie music scene; and someone who enjoys when their bands have a sense of humor. One of the many well-known interviewees, “Weird Al” Yankovic, praises Sparks for their willingness to be funny. Example: An executive asked the unconventional band for “music that you can dance to.” Averse to selling out or engineering pop hits, they delivered the album and song called “Music That You Can Dance To,” a perfectly bubbly tune that makes you want to dance while also thumbing its nose at the suggestion. Did they also invent the Molly Ringwald dance from The Breakfast Club (1985), the signature dance of the 1980s? Possibly.

A combination of Baroque keys, hypnotic repetitions, and playful lyrics, Sparks’ music—written and composed by Ron, sung with a splicing of T. Rex, Freddie Mercury, and falsetto by Russell—borrowed initially from a very British style established in the 1960s. (Most of the film’s interviewees admit to thinking the band was British at first.) But Ron and Russell were born and raised in California, living a somewhat conventional middle-class existence. Ron performed in talent shows. Russell played football. They spent their youth exploring their first love, the cinema, with no interest in adhering to a show’s start time, which made them resist traditional structures in their songs. Ron would later fall in love with arthouse cinema from the likes of Godard and Bergman. After their father died when they were young, their mom took them to see The Beatles, twice, and supported their musical interests. When they first got started in college bands, everyone knew they had something; they just didn’t know what. Producer Todd Rungren describes finding new talent as “sometimes like butterfly hunting. You’re looking for some species that nobody has ever discovered before.” He discovered that in Sparks.

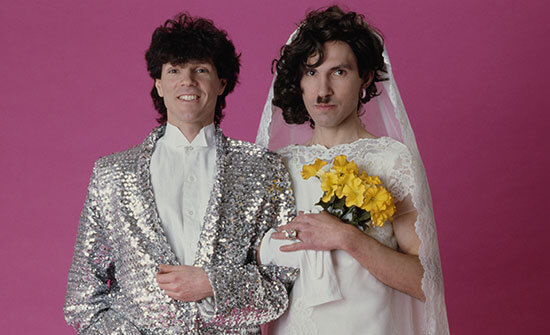

Unfortunately, U.S. listeners generally prefer to know what they’re getting in advance, and Sparks defy clear labels and remain unpredictable. The brothers had better luck with European listeners. They became an oddity and minor sensation not long after appearing on Britain’s Top of the Pops in 1969: Russell, looking vaguely like a young Malcolm McDowell, bops around the stage in perpetual movement. By contrast, Ron, more mysterious and aloof, sporting a toothbrush mustache, sits at his keyboard almost immobile, occasionally giving the camera an exuberantly mischievous side-eye. Not long after the appearance, actress Shelley Winters appeared on a panel show and said, “There was somebody dressed like Hitler playing piano on the BBC.” Whether you associate it with Hitler or Charlie Chaplin, Ron’s mustache and stagecraft created a matinee idol character in a flourish of performance art. (Wright shares a delightful bit of trivia: Paul McCartney spoofed Ron’s signature looks in his video for “Coming Up.”)

Unfortunately, U.S. listeners generally prefer to know what they’re getting in advance, and Sparks defy clear labels and remain unpredictable. The brothers had better luck with European listeners. They became an oddity and minor sensation not long after appearing on Britain’s Top of the Pops in 1969: Russell, looking vaguely like a young Malcolm McDowell, bops around the stage in perpetual movement. By contrast, Ron, more mysterious and aloof, sporting a toothbrush mustache, sits at his keyboard almost immobile, occasionally giving the camera an exuberantly mischievous side-eye. Not long after the appearance, actress Shelley Winters appeared on a panel show and said, “There was somebody dressed like Hitler playing piano on the BBC.” Whether you associate it with Hitler or Charlie Chaplin, Ron’s mustache and stagecraft created a matinee idol character in a flourish of performance art. (Wright shares a delightful bit of trivia: Paul McCartney spoofed Ron’s signature looks in his video for “Coming Up.”)

The Sparks Brothers charts the band’s 25 albums, ups and downs, and something like 300 songs in a linear progression over a 139-minute runtime. Wright uses a wealth of clips from television and concert appearances, surreal music videos that look like comically oddball performance art, and interviews with the press. He makes visual associations with cutaways to movies and TV shows. He incorporates archival photos and home videos from the Maels’ life. Wright also uses animation for dramatic reenactments, including collage-style animations, claymation, and something resembling squigglevision. You’ve no doubt seen these methods used in documentaries before. Still, along with editor Paul Trewartha, Wright creates a fast-paced and dazzlingly watchable film that feels like a living assemblage.

The runtime may prove too demanding for some, especially those not already invested. Then again, others still (myself included) may sit up in their chairs as Wright introduces them to a new dimension in pop-culture history. His enthusiasm is contagious, exhilarating, and like talking to a friend whose opinion you trust about this band that they love. Of course, Wright’s obsession with music is tantamount to the Maels’ fascination with cinema, and so the pairing seems almost inevitable. The director’s films, ranging from Shaun of the Dead (2004) to Baby Driver (2017), feature pitch-perfect needle drops and action scenes cut to music. The Maels have tried to cross over to film several times, resulting in a failed project with Jacques Tati, a brief appearance in the disaster movie Rollercoaster (1977), and another dissolved project with Tim Burton. But 2021 seems to be Sparks’ year. French filmmaker Leos Carax directed their debut screenplay, a musical called Annette, starring Adam Driver and Marion Cotillard, and it debuted at Cannes.

For viewers like me, watching The Sparks Brothers is an eye-opener and somewhat perplexing. I’ve been asking myself, “How have I not been obsessed with these artists my entire life?” I’ve spent the last day or so listening to their music, trying to catch up and discover what Wright couldn’t fit into his documentary. “Sparks is a band you can look up on Wikipedia and know nothing,” says one interviewee. That’s true enough since the Maels have worked hard to ensure some level of mystique. Wright respects their air of mystery and doesn’t explore their personal relationships (apart from Russell’s fling with Jane Wiedlin). Regardless, the film captures their enduring mission of “art for art’s sake.” Ron’s beats dazzle with their mesmeric rhythms, the lyrics never have less than two dimensions, and Russell’s voice gives the experience an uncanny quality. And like my favorite musicians, from Bowie to Bryne, Sparks seem to change their sound with each new album while remaining distinctly themselves. In the end, I only felt grateful to Wright for making this film.

Thank You for Supporting Independent Film Criticism

If the work on DFR has added something meaningful to your love of movies, please consider supporting it.

Here are a few ways to show your support: make a one-time donation, join DFR’s Patreon for access to exclusive writing, or show your support in other ways.

Your contribution helps keep this site running independently. However you choose to support the site, please know that it’s appreciated.

Thank you for reading, and for making this work possible.

Brian Eggert | Critic, Founder

Deep Focus Review